Engaging Without Recognizing? The EU’s Dilemma of Dealing with the Georgian Dream

Since the end of 2024, the European Union has been in search of an efficient policy towards the authoritarian Georgian Dream (GD), which has derailed Georgia’s European integration path and has engaged in anti-democratic law-making and persecution of political opponents, civil society, and independent media.

The EU has come to recognize that its pressure resources and leverage are limited, mainly due to the lack of consensus on foreign policy matters. With Hungary and Slovakia firmly backing the Georgian Dream, the EU is unable to impose sanctions that could hurt the authoritarian regime in Tbilisi. As an interim solution, some EU member states have imposed unilateral measures against officials of the ruling party.

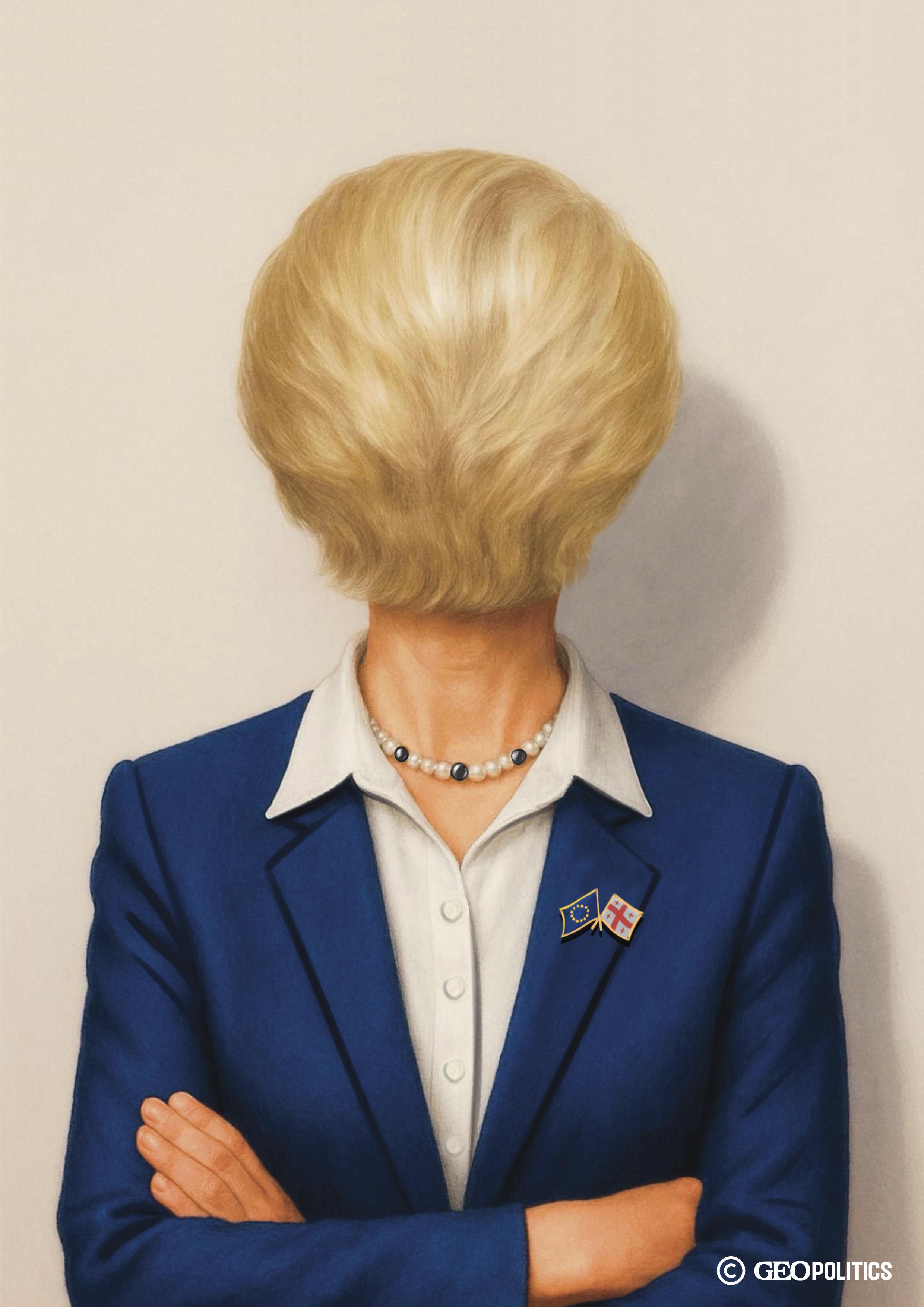

Since 2024, formal engagement between Brussels and Tbilisi is suspended, with the platforms under the EU-Georgia Association Agreement remaining on hold for nearly a year and the EU’s financial assistance to the Georgian government frozen. No high-level contacts have taken place in a sobering message to the GD that “business as usual” can not be sustained. This policy of non-recognition aims to pressure the oligarch to reverse course and re-align with the EU path, something which is still backed by almost 80% of Georgian citizens and is anchored in the country’s Constitution. In the recent joint statement the EU Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos and High Representative/Vice President Kaja Kallas, stressed that “the EU is ready to consider the return of Georgia to the EU accession path if the authorities take credible steps to reverse democratic backsliding.”

However, this non-recognition approach has yet to yield substantial results.

Sanctions are inherently slow-acting tools when it comes to altering the behavior of authoritarian regimes. Targeted officials often adapt, maintain a defiant posture, and wait for pressure from the sanctioning side to ease.

Sanctions are inherently slow-acting tools when it comes to altering the behavior of authoritarian regimes. Targeted officials often adapt, maintain a defiant posture, and wait for pressure from the sanctioning side to ease. In recent months, several top figures from the Georgian Dream who had been sanctioned—among them the Minister of Interior, the Head of the State Security Service, and the Prosecutor-General—have stepped down from their positions. Sanctioning the new wave of officials will take time, giving the regime space to recalibrate and entrench itself further.

At the same time, concerns are growing in Brussels that continued non-recognition might push the Georgian Dream leadership closer to alignment with anti-Western actors. Georgian Dream leaders have intensified contacts with leaders of Central Asian autocracies, including high-level meetings with the presidents of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan. Notably, Mr. Kobakhidze met Viktor Orbán for the eighth time in the last year—more frequently than with any senior EU institutional figure—underscoring the government’s tilt towards Europe’s illiberal bloc.

These arguments are leading some to question whether the EU’s strategy of maintaining a cold shoulder towards the Georgian leadership remains wise. After all, the EU recently held a summit with Central Asian states, celebrating the start of a “new era” in EU-Central Asia relations. This contrast raises doubts about the consistency and effectiveness of isolating Georgia’s government while engaging similarly authoritarian regimes elsewhere.

Fortunately, skepticism towards full engagement with the GD dominates among the EU decision-makers. Most in Brussels and key capitals continue to support a policy of political distancing until the Georgian Dream recommits to the EU path and restores basic democratic institutions. In January 2025, Estonia’s Parliament (Riigikogu) passed a resolution, with 59 votes in favor and nine against, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of Georgia’s “fraudulent” elections, parliament, government, or president. Lithuania has consistently argued that resolving the crisis requires free and fair elections as well as the repeal of laws targeting the political opposition and civil society. The Dutch, the Swedes, the Germans, and the Czechs are also critical of the Georgian Dream and reportedly do not plan to engage with Ivanishvili’s regime. A recent report by the European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee (AFET) called for a reassessment of the EU’s policy toward Georgia and warned of “conditional suspension” of economic cooperation and privileges under the Association Agreement.

In April 2025, Commissioner Marta Kos emphasized the importance of dialogue with the Georgian Dream, stating that while the easiest course is to remain silent, the EU must also understand what it can offer and what the Georgian side is prepared to do. According to the Commissioner, the EU is considering initiating dialogue at a lower level with the possibility of gradually scaling it up— “exploring how we will be able to do this dialogue in the sense that we could be able to bring Georgia back to the European way.” The European External Action Service (EEAS), led by Kaja Kallas, shares this view and is currently considering convening the EU-Georgia Human Rights Dialogue for the first time in two years. The Georgian Dream will likely decline such a dialogue as it would imply that the regime recognizes the problems with human rights, which the ruling party probably will not do for political and propaganda reasons.

While the EU is deliberating what steps to take, the Georgian Dream continues routinely portraying the European Union as part of a global “war party” and the “deep state,” regularly insulting European leaders as ruling party officials continue to seek international recognition and project legitimacy on the global stage. This was a key motive behind Prime Minister Kobakhidze’s participation in the European Political Community Summit in Tirana in May 2025, followed by an umpteenth meeting with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in June. The Georgian Dream’s propaganda outlets swiftly circulated images of Kobakhidze shaking hands with French President Emmanuel Macron, framing it as evidence of EU-level acceptance. Warm encounters with Orbán have become favored propaganda material used to emphasize Georgia’s supposed alignment with core Christian European values—symbolized, in the Georgian Dream’s narrative, by Orbán’s defiance of EU pressure.

For Bidzina Ivanishvili and the Georgian Dream leadership, such moments serve a clear domestic agenda: to reassure their supporters and inner circle that, despite mounting criticism and sanctions, the EU still engages with them—proof, in their narrative, that Western pressure is superficial and ineffective.

For Bidzina Ivanishvili and the Georgian Dream leadership, such moments serve a clear domestic agenda: to reassure their supporters and inner circle that, despite mounting criticism and sanctions, the EU still engages with them—proof, in their narrative, that Western pressure is superficial and ineffective. This places the EU at a crossroads: does it have the resolve to act as a serious geopolitical player, or will it tacitly accept another authoritarian regime as a candidate in its neighborhood?

Why the Georgian Dream Still Courts the West?

Despite its announcement of a “pause” in the EU accession process, the Georgian Dream’s leadership remains unwilling to abandon the European track formally. Instead, it carefully manipulates language to obscure the fundamental shift in direction, telling pro-European voters that EU membership remains the official goal while taking actions that contradict this claim. Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze has publicly stated that Georgia will still fulfill “over 90%” of the Association Agreement obligations by 2028 and that the country will be ready for EU accession by 2030—statements designed to maintain the illusion of continuity even as Brussels imposes sanctions and freezes dialogue.

There are clear strategic reasons for the Georgian Dream’s reluctance to sever ties with the West fully. First, the ruling party is highly sensitive to the domestic narrative that it is diplomatically isolated and unwelcome in Europe. This vulnerability explains its recent flurry of diplomatic activity.

The Georgian Dream is wagering that Europe’s geopolitical pragmatism will eventually override its normative commitments.

Second, the Georgian Dream is wagering that Europe’s geopolitical pragmatism will eventually override its normative commitments. The EU’s increasing interest in connectivity across the South Caucasus—via the Middle Corridor infrastructure, the Black Sea electricity cable, and planned energy deals with Azerbaijan and Central Asia—gives the ruling party hope that Brussels will ultimately prioritize strategic cooperation over democratic backsliding. This logic gained further traction following the April 2025 EU-Central Asia Summit, which hailed a “new era” in relations, and HRVP Kaja Kallas’s official visit to Baku just weeks later.

The Georgian Dream’s calculation is straightforward: in a context of deepening EU-U.S. trade disputes, shifting energy routes, and an Armenia–Azerbaijan peace deal that could unlock regional stability, Brussels will be under pressure to engage with whomever controls Georgia, democratic or not. Ivanishvili’s long-term bet is that Georgia’s geography and infrastructure will make it indispensable to the EU, allowing his regime to rebrand itself as a pragmatic, if illiberal, partner in a broader Eurasian connectivity architecture. The question now confronting EU policymakers is whether or not they are willing to reward that wager.

What Kind of Engagement?

Brussels is becoming increasingly uncertain about how to handle Georgia. While the country has featured in the last three European Council meetings, the EU still lacks a coherent strategy or effective leverage to address Georgia’s deepening democratic crisis. Concerns are growing that Georgia may be slipping away, politically and strategically.

The EU’s limited engagement is primarily due to competing priorities, including the war in Ukraine, strained EU-U.S. relations, and internal democratic backsliding. As Georgia risks falling off the agenda, some in Brussels argue that the current policy of isolation and sanctions has failed to deliver results and may be driving the Georgian Dream closer to Russia, Iran, and China.

Critics of disengagement point to the EU’s pragmatic relations with authoritarian regimes in Central Asia, Türkiye, and Azerbaijan, and suggest Georgia should not be treated differently.

At the same time, others caution that complete disengagement is unrealistic, especially in areas like tax transparency and organized crime. Georgia also remains key to the EU’s energy diversification strategy, particularly as part of alternative transit routes bypassing Russia, highlighted by recent EU outreach to Turkmenistan and the South Caucasus.

Yet, EU officials remain wary of giving the Georgian government any opportunity to claim that Brussels has moved past the fraudulent October 2024 elections and returned to “business as usual.”

This is where the EU finds itself walking a tightrope. The dilemma is whether and how to engage with the Georgian authorities, whose ruling party has been denounced by the European Parliament as illegitimate and responsible for state capture, without legitimizing them. Even low-level engagement risks being exploited by the Georgian Dream to create the impression that Brussels has returned to its former routine. This, in turn, undermines the EU’s credibility and emboldens authoritarian actors across the region.

The regime’s central goal is to secure international recognition for Bidzina Ivanishvili’s authoritarian rule—and it has shown it will use any opening from Brussels to claim exactly that.

If the EU does decide to re-engage, it must do so with a well-defined set of goals and safeguards. The context remains dire: dozens of political prisoners remain behind bars, civil society activists are beaten and harassed, NGO leaders are about to face criminal liability, political parties might be outlawed by the end of this year, the propaganda machinery is working full force with the Russian message box, the legitimacy of the 2024 elections is widely disputed, and the EU, the U.S., and the UK have sanctioned Georgian Dream-affiliated individuals and media outlets. The regime’s central goal is to secure international recognition for Bidzina Ivanishvili’s authoritarian rule—and it has shown it will use any opening from Brussels to claim exactly that.

The EU has seen this play before. After the 2020 Parliamentary elections, it was European Council President Charles Michel who brokered a deal between the ruling party and the opposition. The Georgian Dream signed the agreement only to walk away from every commitment: no judicial reform, no electoral reform, no improvements in the rule of law, no power sharing, and no 43% barrier as a tripwire for the new parliamentary elections. Instead, the party used the façade of dialogue to consolidate power further and marginalize dissent.

If Brussels chooses to re-engage with Georgia, it must do so transparently, guided by a clear strategy, a well-defined timeline, and an accountability framework.

If Brussels chooses to re-engage with Georgia, it must do so transparently, guided by a clear strategy, a well-defined timeline, and an accountability framework. Unlike in 2021, when the EU lacked real leverage and was hesitant to use even what it had, today the EU possesses both meaningful carrots and sticks. Engagement must not be mistaken for endorsement.

The EU should tie any re-engagement to specific, measurable steps by the Georgian Dream, such as the release of political prisoners, the repeal of anti-democratic laws (including those targeting civil society and the media), and the organization of new, credible parliamentary elections to resolve the political crisis.

In exchange, the Georgian Dream government could receive:

- Restoration of official EU-Georgia formats;

- Recognition of legitimacy as a dialogue partner for Brussels;

- Partial unfreezing of suspended financial assistance;

- Gradual normalization of political relations with EU institutions.

These steps could reopen accession talks and grant Georgia access to previously unavailable programs like Digital Europe. Most importantly, they could revive EU interest in the Black Sea electricity cable, the renewed digital link with Georgia and the South Caucasus, as well as broader trade and economic connectivity via the Middle Corridor.

At the same time, the EU must make clear that failure to meet these conditions will carry serious consequences. These sticks could include:

- Coordinated EU sanctions on all Members of Parliament who voted for repressive laws, following the model already used by several member states;

- Coordinated sanctions on Mr. Ivanishvili and his enablers, including the propaganda industry and the businesses that sustain the Georgian Dream;

- The initiation of formal infringement procedures for violations of the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA)—especially articles relating to civil society engagement, the rule of law, and democratic governance;

- A policy statement that the EU will not abide by the restrictive legislation violating the freedom of assembly and restricting the work of the country’s vibrant civil society.

A coalition of willing EU member states could form a Contact Group on Georgia to monitor the situation, coordinate pressure, and offer mediation, ensuring that engagement is principled rather than passive.

Finally, a coalition of willing EU member states could form a Contact Group on Georgia to monitor the situation, coordinate pressure, and offer mediation, ensuring that engagement is principled rather than passive. As the ECFR suggested in a recent policy recommendation, the Weimar Three (Germany, France, and Poland) could play a pivotal role in the new mediation.

This two-track approach—conditional incentives paired with enforceable red lines—offers Brussels its best chance to reassert influence in Georgia without legitimizing authoritarianism.