The days of the mid-90s and early 2000s—when the EU was a dominant player in its neighborhood and the accession process served as a viable means to transform aspiring countries—are long gone. To remain relevant, the EU must now adapt by making its decision-making process more flexible. It needs to shift from passivity to proactive engagement, moving beyond merely understanding what needs to be done but lacking the means to act. This cannot be done without finding ways to overcome the vetoes of individual states, which deadlocks the EU’s ability to act.

To remain relevant, the EU must now adapt by making its decision-making process more flexible.

The requirement for unanimity, combined with Russia’s “Trojan horses” within the bloc, severely limits its ability to maneuver as a true global power. Recent developments in the Eastern neighborhood, particularly in Georgia, present a serious challenge for the EU. Once firmly pro-European, Georgia now teeters on the brink of falling into Russia’s orbit—held back only by the determined resistance of its people.

In its relations with Georgia, the European Union faces stiff competition from Azerbaijan, China, Russia, and Türkiye. Unlike the EU, these countries are willing to unconditionally support the Georgian Dream (GD) government without demanding democratic reforms.

In its relations with Georgia, the European Union faces stiff competition from Azerbaijan, China, Russia, and Türkiye. Unlike the EU, these countries are willing to unconditionally support the Georgian Dream (GD) government without demanding democratic reforms. Their flexibility in decision-making makes them much more appealing to the Georgian Dream than the EU.

A mix of coercion, tolerance for human rights violations, investments and assistance without reform conditions, and unrestricted trade—free of tariff and non-tariff barriers—created a comfortable space for the authoritarian Georgian government. Conversely, the EU failed to win over the Georgian Dream leadership by offering EU membership in exchange for democratic transformation. By granting Georgia candidate status in 2023, the EU surrendered yet another key leverage over the GD.

So far, the “offers” from Ankara, Moscow, Baku, and Beijing have tilted the balance in their favor, at least when it comes to influencing the Georgian government. However, unlike GD leadership, they have failed to capture the hearts and minds of the Georgian people, who continue to fight for their country’s European future. Russia has become more aggressive, waging full-scale wars against neighbors that resist its influence. China is expanding its economic reach through the Belt and Road Initiative, securing access to key land routes—such as Georgia’s East-West Highway, now being built by Chinese companies—and strategic seaports, including Anaklia, where a Chinese-Singaporean consortium, already sanctioned by the US for corruption, is set to take the lead.

Speaking with one voice should not become a weakness that renders the EU less competitive and incapable of bold action.

In this ongoing struggle between pro-European society and the pro-Russian Georgian Dream, the EU must act decisively rather than remain on the sidelines. The bloc’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) was designed to strengthen the Union but is now only weakening it. Speaking with one voice should not become a weakness that renders the EU less competitive and incapable of bold action.

The case of Georgia highlights the shortcomings of the CFSP, which, despite being established by the Treaty of Maastricht in 1993 and strengthened by subsequent treaties—Amsterdam (1999), Nice (2003), and Lisbon (2009)—fails to respond effectively to fast-changing realities on the ground. According to Article 24(1) of the EU Treaty, the CFSP “shall be defined and implemented by the European Council and the Council acting unanimously, except where the Treaties provide otherwise.” This unanimity requirement has created a vicious cycle: while the EU possesses the necessary tools and mechanisms, their application is effectively blocked by the need for consensus—especially with the presence of GD-friendly and Russia-aligned governments like those in Budapest and Bratislava.

The EU’s response to the violent suppression of peaceful protesters in Georgia exposes its operational limitations.

In 2020, the EU adopted Council Regulation (EU) 2020/1998, enabling restrictive measures against serious human rights violations and abuses. The regulation is based on breaches of fundamental freedoms, including the right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression. However, the EU’s response to the violent suppression of peaceful protesters in Georgia exposes its operational limitations.

While the United Kingdom and the United States have imposed sanctions on high-ranking officials from Georgia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) and on Georgian Dream’s founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, for human rights violations and brutal crackdowns, the EU’s only adopted measure was to suspend visa-free travel for diplomatic passport holders. Yet, this sanction is largely symbolic—easily circumvented, as those targeted also hold ordinary passports, allowing them access to the EU and Schengen zone countries. Hungary already announced that it will not enforce the EU decision to suspend visa-free travel for Georgian diplomatic passport holders. This discrepancy underscores the EU’s inability to take decisive action in the face of democratic backsliding and human rights abuses in Georgia.

The Lisbon Treaty provided a pathway to extending Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) to Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) matters through the use of so-called passerelle clauses. Article 31(2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) states: “The Council shall act by a qualified majority when adopting a decision defining a Union action or position on a proposal which the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy has presented following a specific request from the European Council, made on its initiative or that of the High Representative.”

Despite this provision, the EU remains hamstrung by its unanimity requirement. The bloc’s new High Representative, Kaja Kallas, attempted to push for sanctions against Georgia at her first meeting of EU foreign ministers but failed to secure the necessary consensus. This failure showed the EU’s deep divisions over Georgia, driven by three key factors:

This concern over maintaining diplomatic ties was notably echoed by EU Ambassador Paweł Herczyński who, in justifying his controversial post-election meeting with the GD’s Foreign Minister Maka Botchorishvili on 26 October 2024, emphasized the need to keep dialogue open—even at the cost of inaction.

The EU’s response to the GD’s actions is too little, too late—reminiscent of its delayed reaction to Belarus’s authoritarian turn in 2020. Instead of taking the initiative, the EU allowed the Georgian Dream to dictate the agenda and responded (not sufficiently) only after the fait accompli of grabbed power and captured institutions.

The EU’s immediate response to the Georgian elections was not based on unanimity. Only half of the block – 15 foreign ministers of EU member states, made a joint statement stressing that “the violations of electoral integrity are incompatible with the standards expected from a candidate to the European Union” and “are a betrayal of the Georgian people’s legitimate European aspiration.” The EU’s already ambiguous stance weakened further following Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s visit to Tbilisi the day after the elections, during which he congratulated the GD’s newly appointed Prime Minister, Irakli Kobakhidze. Attempts to discuss the situation in Georgia in several Foreign Affairs Councils in 2024 and not managing to agree on the course of action or any concrete measure buoyed the GD in believing that they could get away with the crackdowns and human rights violations guaranteed that their “friends in the EU” would block any sanction at the EU level.

Moreover, the statement by the EU HRVP Josep Borrell on 27 October 2024, announcing the deployment of a technical mission to assess the post-election situation, proved either premature or insincere as no follow-up action was taken. The EU faltered again on 16 December 2024 when, due to Hungary and Slovakia’s veto, EU foreign ministers disagreed on imposing personal sanctions against GD officials.

These examples highlight that the EU is sluggish in responding to crises in its neighborhood. At the same time, countries like China, Russia, Türkiye, and Azerbaijan quickly moved to accommodate Georgian Dream officials. Unlike the EU, Beijing, Moscow, Ankara, Yerevan, and Baku wasted no time legitimizing the 26 October 2024 general elections, never questioning the results and congratulating the newly elected leaders. Baku, Yerevan, and Abu Dhabi have even hosted official delegations of the Georgian Dream.

As of the publishing of this piece, no EU leader has visited Tbilisi to show solidarity with protesters fighting for Georgia’s European future. The ambassadors of the EU member states – Hungary, Slovakia, Italy, as well as the Ambassador of the UK – have even paid official visits to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Georgian Dream propaganda used these mixed signals well to show that business continues with the EU as usual and the critical statements from various individual politicians are made under the influence of the “deep state” or are the result of either Europe’s internal problems or personal animosities of concrete politicians. Sporadic critical statements from the EU leaders, such as Kaja Kallas’ recent tweet that “Georgia falls short of any expectation from a candidate country” and that “the EU stands with the people of Georgia in their fight for freedom and democracy,” only reinforce the perception that the EU is toothless especially since such statements are often followed by calls from various EU capitals “that the words are not enough” and that Kallas should actually visit Tbilisi and show support for the protesters on the ground.

The EU’s failure to acknowledge the shifting geopolitical landscape costs it influence in Georgia, while authoritarian powers fill the vacuum.

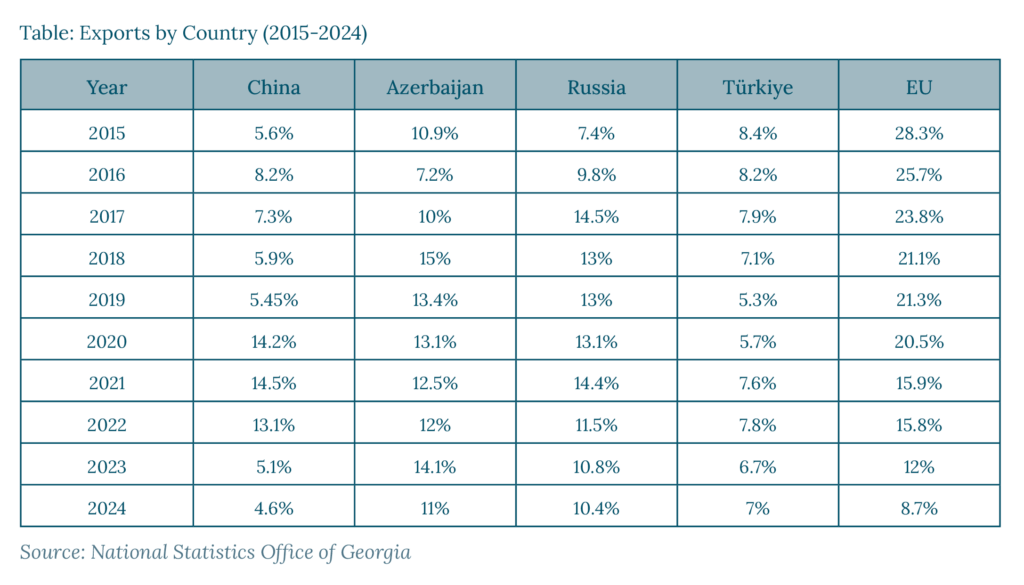

The EU has also been unable to use free trade as its leverage. As shown in the previous issue of this journal, the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) agreement has not led to a planned trade turnover increase. Since 2015, the EU’s share in Georgian exports has plummeted—from 28.3% in 2015 to just 8.7% in 2024 (See the table above). The EU’s failure to acknowledge the shifting geopolitical landscape costs it influence in Georgia, while authoritarian powers fill the vacuum.

Meanwhile, among Georgia’s top investors, Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and China turn a blind eye to the lack of judicial independence, elite corruption, and human rights violations. With the EU, France, Germany, Sweden, and the UK suspending financial aid to Georgia, it is only a matter of time before the Georgian Dream turns to China or Azerbaijan for support. This raises the growing risk of Georgia falling into a “debt trap” scenario where economic dependence on authoritarian powers could further erode its sovereignty. A clear demonstration of looking for alternative finances was the recent visit of GD Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze to the United Arab Emirates and the Memorandum of Understanding, which, as GD leaders claimed, pledges the investment of USD 6 billion in Georgia’s real estate sector.

The European Union cannot afford to remain a bystander while the Georgian people fight for their European future. Freezing the accession process, withholding direct budgetary support, or making symbolic gestures—such as sending technical missions or restricting visa-free travel for diplomatic passport holders—will not deter the Georgian Dream from its authoritarian course. It will only strengthen the GD leaders’ belief that the EU will only talk the talk and not walk the walk.

The EU member states should start acting unilaterally, attempting to cross the bridge one by one rather than collectively.

However, for the walk to be successful, the EU member states should start acting unilaterally, attempting to cross the bridge one by one rather than collectively. Germany, Czechia and the Baltic states have already taken independent action under their national legislation, proving that targeted measures are possible. Other EU members must follow suit. For instance, individual EU member states can impose bilateral sanctions, ban Georgian Dream members from entering their countries, and declare that bilateral relations are on hold or relegated to the technical level in parliamentary resolutions or official government statements.

Furthermore, EU member states must not accept Georgian ambassadors appointed by Mr. Kavelashvili, a football player turned ultra-right politician turned President. They should also not hold formal bilateral or multilateral talks with the oligarch’s government. Increasing the perception of a total lack of legitimacy, even at the bilateral level, can be a game-changer in Mr. Ivanishvili’s calculations.