This journal exposed in vivid detail how Georgia’s government has rapidly embraced populist conservatism, coupled with a foreign policy that is nothing short of delusional. How can a government that stifles civil society, infringes on media freedoms, resorts to violence against opponents, and structurally cheats in elections still claim to aspire to European Union membership and expect to make imminent progress on this path? The dismay of activists and commentators is entirely understandable. The European Union has made it clear that the accession process is on hold for now. However, there is one pre-accession country example where Brussels tolerates similar behavior: Serbia.

A country roughly twice the size of Georgia by population has a complicated relationship with the liberal West, an Orthodox Christian heritage, and ties to Russia. Like Georgia, Serbia has been led by one political party since 2012. That party is dominated by a single man: Aleksandar Vučić.

Serbia was granted the EU candidacy in 2012 and opened accession negotiations in early 2014. Twenty-two out of 35 chapters of the membership negotiations have been opened, and two have been provisionally closed. In 2023, the EU formal report on the accession identified shortcomings but kept highlighting progress.

In stark contrast, the OSCE ODIHR, an international election watchdog, issued a damning report about the electoral process in 2023, openly speaking of the ruling party’s “overwhelming advantage.” Indeed, only one election has been held in Serbia since 2012 under the regular election schedule. The ruling party schedules snap elections whenever it wants. This gives the opposition little time to organize or campaign. Vučić constantly promotes the sense of emergency to trigger early elections, one of his key political instruments to secure political continuity.

In 2024, Freedom House, an international watchdog, reported a considerable drop in all democracy and governance ratings. Serbia’s democracy had been steadily declining since 2014, and in 2020, Freedom House no longer qualified it as a democracy. Now, Serbia is grouped among the “transitional or hybrid regimes,” just like Georgia.

Yet, Georgia boasts a considerably higher overall democracy score of 3.06 on a scale of one to seven, where one is a perfectly functioning consolidated democracy, and seven is a bloody dictatorship. In 2024, Serbia’s score was a mere 3.61. Furthermore, the Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International places Serbia in 104th position out of 180 countries in 2024, while Georgia is evidently performing much better, ranking 49th.

This raises the pertinent question of whether the Georgian Dream still has a long way to go to hit rock bottom. Are the pro-government pundits right in saying that progress towards the EU could still be achieved despite state capture and the repression of independent institutions and free voices? Let us look deeper at Vučić’s experience and tactics and try to discern what keeps his antics still palatable for the EU. And for how long that patience may last.

The “Vučić system” is based on three pillars: a party-based patronage network, security services, and unfettered propaganda.

Just like other populist authoritarians from Venezuela to Hungary, Vučić’s tactic has been to capture the state institutions gradually. The “Vučić system” is based on three pillars: a party-based patronage network, security services, and unfettered propaganda. This edifice was constructed stage by stage.

Having succeeded in rebranding the far-right, Srebrenica genocide-denier Serbian Radical Party (SRS) into a frequentable and (at least on paper) pro-European Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) is perhaps Aleksander Vučić’s most masterful political feat.

To consolidate and durably hold on to power, SNS took advantage of the pre-existing patronage networks that linked political parties to clients like state-owned enterprises and down to the hospitals, schools, and sports clubs. Before SNS’s rise, these were controlled by several key political actors and were used to distribute favors (such as appointments, social aid, appointments with a good doctor, or placements in a good school), collect rents (in the form of kickbacks, through football hooligans-cum-racketeers) and influence politics (e.g., through municipal media and tabloid press).

SNS took control of these, sharing modestly with its junior partner, the Serbian Socialist Party (SPS). The network flourished: SNS claimed to have over 700,000 card-carrying members in 2018, making it the largest party in Europe. And no wonder – the SNS card gives preferential access to public services and, crucially, employment. Neither is party membership a mere formality: as a minimum, newbies are expected to attend party chapter meetings, where they are indoctrinated in party views.

When capturing the institutions, Vučić prioritized security and intelligence services. Immediately after landing as First Deputy Prime Minister, he claimed the defense portfolio, became the secretary of the National Security Council, and the security services coordination supremo, the position he kept after becoming the President in 2017. Party cadre was massively promoted within the Security Intelligence Agency (BIA) and other security-intelligence agencies, and personal loyalty to Vučić remains crucial when picking the head of intelligence. SNS adversaries and allies were (and likely continue to be) targeted by massive surveillance, which only became public after a local NGO successfully sued BIA at the European court of Human Rights for concealing the open data. The party control perdures to this day and has been complemented by significant infiltration of Russian influences. Previous, brazenly pro-Russian head of BIA, Aleksandar Vulin, stepped down in 2023 after being sanctioned by the U.S. for helping Moscow in its “malign” activities. But he stayed on as vice Prime Minister.

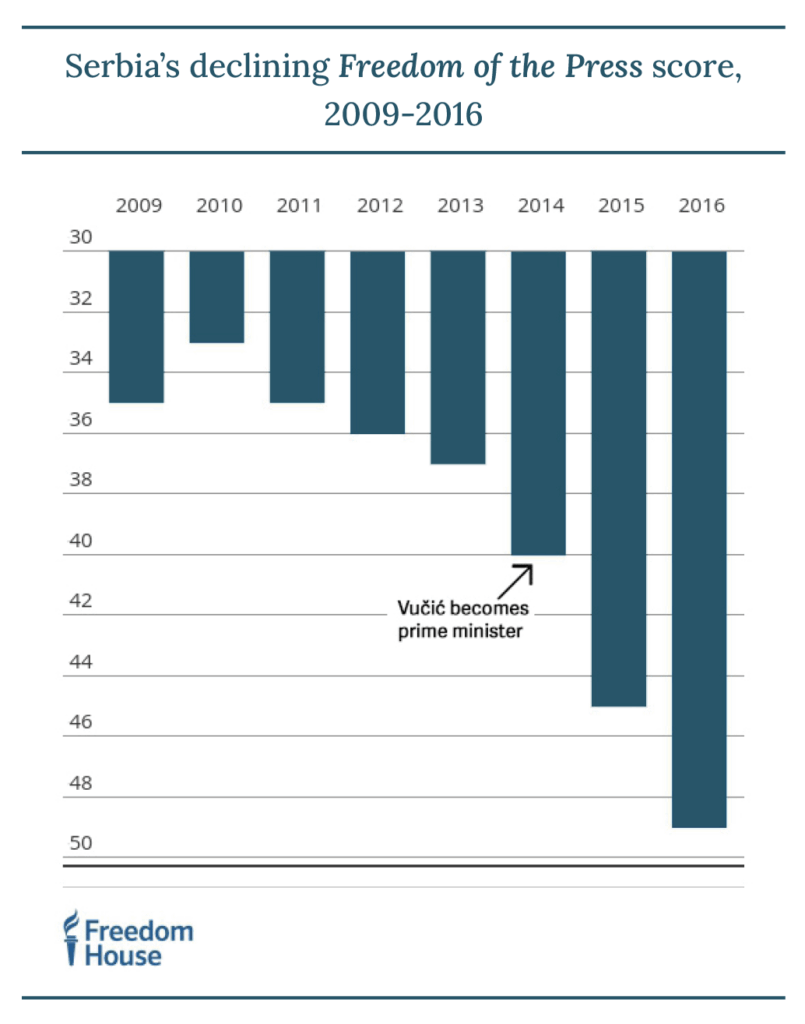

Media subversion is one of Vučić’s strong suits. After all, he served as the Minister of Information under Slobodan Milosevic’s genocidal rule and already has mastered the country’s media scene as well as the techniques of pressure and intimidation. Rebranded as a committed democrat, Vučić often warped market forces to shape the country’s media scene to his liking. By 2012, Serbia had a panoply of media operators – including influential independent television stations, local press, and several state-controlled outlets – national and regional TV stations, newspapers, and a state news agency. However, although the media’s political and opaque financial patronage has long been a concern, they took off after 2012, flooring the press freedom index (see the graph above).

The preferred method for bringing media to heel has been to starve the opposition-minded outlets of cash – by cutting public service advertising and contracts from state-owned companies – while simultaneously subsidizing loyalty. In this way, PINK TV, which previously was mostly airing entertainment content, received over EUR 7 million in public contracts in 2014-2016 and became a keystone in Vučić’s propaganda machine.

The Serbian government also doggedly resisted the calls to privatize the state-owned outlets. For example, Tanjug, the state news agency whose privatization the EU was demanding, was formally closed down in 2015 but functioned as a government mouthpiece until 2021, when its copyrights were ceded to the shady company created by a folk singer whose budget jumped from EUR 500 in 2019 to EUR 7.2 million in 2021. First, bankrupting and then selling the media assets to well-connected businesses has been one of Vučić’s preferred tactics.

The EU progress report for 2023 highlights the highly problematic physical and verbal intimidation of journalists by officials (183 attacks on journalists reported in 2023), intimidatory litigation by officials, politicians, and connected businesspeople, and harassment by the loyal media regulator (REM). As of today, four out of five national broadcasting licensees are held by strongly pro-governmental companies, while the regulator has delayed since 2022 the attribution of the fifth and final license.

These are, of course, just the largest blocks in Vučić’s Lego castle of autocracy. Add to that neutered Parliament, subservient courts, and public administration that became synonymous with the ruling party, and you get your basic autocratic infrastructure.

But how could one speak about progress – let alone progress towards the EU – under these circumstances?

In a way, Serbia has had the advantage of a very low starting point. Long after Milosevic, the country was cast as Europe’s main villain. European diplomats and politicians were fed up with the inefficiency, broken promises, and corruption of the so-called “democratic forces.” Their bickering and incompetence facilitated the SNS’s rise to power. Vučić campaigned on anti-corruption and effective government in 2012 and made good on his promises, arresting a notorious tycoon and a known drug lord by 2014. And his unquestioned nationalist credentials allowed Vučić to sideline the most odious veterans of Serbian far-right politics – Tomislav Nikolic and Vojislav Seselj. Not only was Serbia no longer seen as the Balkan spoiler-in-chief, but Vučić also signed an agreement on the normalization of relations with Kosovo in 2013 and attended the commemoration of the Srebrenica massacre in 2015. In a dramatic and welcome break from the past, these steps earned him a reputation in Europe as a pragmatic and responsible politician who could get things done. And even though the SNS was simultaneously taking steps to throttle the media and capture state institutions, its EU neighbors chose to focus on the positive.

Leveraging economic ties for political benefit and balancing the interests of the EU, China, and Russia has become a hallmark of Vučić’s charm offensive.

From 2014 onwards, when Vučić gradually consolidated his power to become president in 2017, his government made a significant effort to relaunch the economy and investment. 2.2% of GDP was spent on state aid to enterprises – much of it to bolster patronage networks. But importantly, Belgrade launched gigantic infrastructure, transportation, and investment projects that the government heavily subsidized. An important part of this support came from China and the United Arab Emirates. Still, over 12 years, it received foreign direct investment (FDI) from the EU countries totaling EUR 21.3 billion, which accounts for 58.4 percent of all FDIs in Serbia during that period. Leveraging economic ties for political benefit and balancing the interests of the EU, China, and Russia has become a hallmark of Vučić’s charm offensive. This policy continues: most recently, the European Commission has developed a strategic interest in the country’s lithium mines, pressing ahead with partnership despite massive public protests over the mine’s anticipated ecological impact. Similarly, purchasing Rafale fighter jets from France in 2024 is Vučić’s other typical invitation for the European partners to choose economic interest over principles. In the period of 2014-2020, when these projects were initiated and launched, SNS tightened control over client networks (including with EU money), marginalized the opposition, and subverted the free press.

This period saw the intensification of collaboration between the security services on one side and football hooligans and organized criminal groups on the other. Although present since the 1990s, it took a form of partnership where reportedly SNS exchanged protection for these groups pressuring its political opponents from the political party and activists – a claim for which the investigative journalists were targeted by a defamation campaign. The tabloid press – with links to intelligence services and organized crime – was often used to target activists. More broadly, civil society organizations were increasingly targeted, with the EU Serbia Report of 2019 speaking of the “environment not open to criticism” and “harsh campaigns” against human rights and civic activists. In a concomitant development, the government started creating a parallel network of government-sponsored NGOs (GONGOs), often with names similar to known groups, which occupy media space, delegitimize their critics, and shield the SNS from criticism.

Yet these worrying developments contrasted with symbolic progress in others: for example, Serbia has held Belgrade Pride Weeks, previously targeted by official bans and extreme violence, since 2014. Moreover, Vučić appointed an openly gay female prime minister, Ana Brnabic, in 2017, which his government repeatedly used to shield itself from criticism about rights restrictions. Brnabic, of course, proved to be as loyal to Vučić and his conservative policies as others in his cabinet.

The pandemic and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine have hardened Serbia’s policies. Vučić used the pandemic to declare emergency rule, introduce a military curfew, and crack down on opponents. He took credit for getting vaccines from Russia, China, and the EU. He cast these as the benefits of a “balanced” foreign policy. Serbia has carefully managed its distance from the EU since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. It has partly applied EU sanctions but also welcomed hundreds of thousands of Russians, boosting domestic consumption and the economy. Vučić is trying to court Moscow with the help of Aleksandar Vulin, a U.S.-sanctioned former intelligence chief. At the same time, Belgrade vies for the support of Brussels, Paris, and Berlin and shows the Europeans and US that he holds the keys to the Balkan stability by staging periodic escalations in Kosovo.

For Georgians, similarities with Serbian developments in the past 12 years abound. A brief glance at the current Georgian and Serbian government mouthpieces is even more telling: Vučić’s government has been pushing conspiracy theories, tagging civil society as spies on foreign pay, and increasingly channeling traditional religious conservatism. Most commentary about the war in Ukraine comes from Russia, involving current and retired Russian military.

In the past decade, the country lost an estimated 350 thousand people to emigration, mostly women and young people of working age. As in Georgia, Serbia heavily relies on remittances (mostly from Europe; see graph above) to keep afloat impoverished suburban and rural areas where the official social protection net is scant and public services sub-optimal—people who often vote for the ruling party to retain control.

Just like the Georgian Dream recently, SNS has pursued the foreign policy “balancing,” inviting Russia and, especially, China to make strategic investments, which are then likely funneled into the clientelist networks through corrupt schemes.

The state institutions and courts are captured, and even massive protests – like the recent ones in Serbia against lithium mines, or against violence, or the one against the “agents law” in Georgia – seemingly fail to bring long-term change.

Georgia has no such pivotal role, and its credibility with the EU was primarily based on its status as the frontrunner in reforms – which has by now all but evaporated.

Yet, there are differences. For once, there is a difference in the starting point: Serbs have legitimate trauma associated with the Belgrade bombings that makes them highly skeptical of Western institutions. The country holds the key to fragile stability in the Balkans, and keeping it broadly on track toward the EU is in the pragmatic interest of Brussels, Berlin, and Paris, among others. Vučić has cultivated a close relationship with the outgoing EU enlargement commissioner Olivér Várhelyi – just like the Georgian Dream did – to the extent that the Commissioner was accused of embellishing the EU reports to Serbia’s favor. Georgia has no such pivotal role, and its credibility with the EU was primarily based on its status as the frontrunner in reforms – which has by now all but evaporated.

Serbian leadership is also positioned to provide significant “carrots” – investment opportunities and subsidies, strategic lithium reserves, and promises to normalize relations with Kosovo and not undermine Bosnia’s territorial integrity – things that Georgian leadership lacks.

The only significant difference working in favor of Georgia’s European future is the position of its citizens. In Georgia – 86% support EU membership.

The only significant difference working in favor of Georgia’s European future is the position of its citizens. In Georgia – 86% support EU membership. By contrast, according to recent polls, 46% of Serbs say Russia is their most important ally, and only 40% said they would vote for EU membership if a referendum were held. Thirty-four percent would vote ‘No’.

Perhaps Georgians can convert their strong opinion into a political choice. A dramatic difference of opinion from the Serbs regarding the importance of joining the EU, could still prove to be a tipping point. Still, the electoral process can be hacked, and the outcome remains to be seen in October.

Relying on push or pull factors from the EU to compensate for internal political shortfalls decisively is a naïve hope. Authoritarian populist regimes have found ways to hack into the EU decision-making processes, primarily by hiding behind the “sovereignty” banner

If anything, Serbian experience tells us that relying on push or pull factors from the EU to compensate for internal political shortfalls decisively is a naïve hope. Authoritarian populist regimes have found ways to hack into the EU decision-making processes, primarily by hiding behind the “sovereignty” banner (a trick that the Georgian Dream has taken up) and by appealing to so-called “pragmatic” – geostrategic, economic, and business – interests in bilateral and multilateral relations. If they can keep the domestic protest insulated, circumscribed to street protests without access to political decision-making mechanisms and official positions, there is little that the EU can tangibly do.

Serbia is at the heart of Europe. Germany, Austria, and other neighbors want to see it in the EU as quickly as possible, which gives President Vučić ample room for bargaining. In other words, integrating Western Balkans as a regional entity is in the Union’s strategic interest, whereas Georgia is on the periphery and increasingly isolated.

If the Georgian Dream decides to go “full Vučić,” Georgia’s EU perspective would be definitively dead and buried.