The South Caucasus has long been defined by dynamic geopolitical change and challenges. But the past several years have been marked by the most dramatic shifts in regional geopolitics. For Georgia, the course of reform and democratization has become beset by internal obstacles and serious setbacks well beyond the lingering geopolitical burden of the legacy of the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008. Azerbaijan, for its part, has emerged as a more assertive and, at times, more aggressive geopolitical power, defeating Armenia in a 44-day 2020 war and seizing Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023. Against this significant shift in regional geopolitics, Armenia has weathered the most severe threats and embarked on the most decisive strategic reorientation.

The most notable element of this new geopolitical landscape of the South Caucasus is the broader context of Russia’s failed invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Obviously, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine triggered much more profound repercussions far beyond the region. For the three countries of the South Caucasus, there were three important yet indirect considerations.

The first of these repercussions from Russia’s failed invasion of Ukraine was the onset of an unusual period of Russian distraction as Moscow quickly became overwhelmed by its shock of military failure. Diversion of Moscow’s attention elsewhere offered a rare respite for Russia’s other neighbors. This distraction only downgraded other agenda items of Russian interest in the South Caucasus, from occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia to Nagorno-Karabakh.

This period of Russian distraction or “geopolitical neglect” also encouraged Azerbaijan to rely on the power of arms in a display of geopolitical force projection to militarily move against Armenia and target the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Moscow can no longer hide the steady erosion of its capacity for force projection and the slow death of the “myth of Russian military might.”

A second related element of the aftermath of the failed invasion of Ukraine was the military weakness of the much-vaunted Russian military power and prowess. The reaction to the rather surprisingly sudden and serious setbacks for Moscow was far-reaching, with a more realistic revelation from Central Asia to the South Caucasus of the weakness of the inherent threat of Russian hard power. This also means that Moscow can no longer hide the steady erosion of its capacity for force projection and the slow death of the “myth of Russian military might.”

Further, in assessing Azerbaijan’s military victory over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023, Russia’s failure to deter Azerbaijan and the passive proximity of the Russian peacekeepers suggests complicity. In terms of power perception, however, Russian weakness in the face of the Azerbaijani use of force has been matched by Azerbaijan’s capability to challenge Russia. This is also seen in the embarrassing humiliation of the Russian peacekeepers, the challenge to Russia’s power and position in the South Caucasus, and Azerbaijan’s open defiance of Russia. Against that backdrop, Russia’s position in the South Caucasus is now one of weakness, not strength, and remains more insecure than self-confidence.

However, the broader context of regional geopolitics was observed on a different battlefield. This third factor stemmed from the “success” of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. More specifically, Moscow was quite successful in terms of three strategic outcomes. First, Russia was able to unite the West with a rare commitment to resolve. A second Russian achievement was seen in the immediate restoration of the geopolitical relevance of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), as seen more recently in the Finnish and Swedish accession to the alliance, as well as the validation of the Georgian and Ukrainian pursuit of NATO membership as the only way of ensuring security in the face of Russian expansionism.

Russia was also quite effective at demonstrating the imperative for its neighbors to strengthen their independence and sovereignty based on self-sufficiency in the wake of Russian weakness.

Perhaps more significantly, Russia was also quite effective at demonstrating the imperative for its neighbors to strengthen their independence and sovereignty based on self-sufficiency in the wake of Russian weakness. This last factor only vindicated Georgia’s long-standing recognition of the Russian threat, a lingering legacy of the often-ignored lesson from Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia. It also encouraged Armenia to embark on its own strategic reorientation away from Russia in a pivot to the West.

From an Armenian security perspective, the threat environment has long been clear. Situated in a threatening neighborhood, Armenia has become accustomed to being a prisoner of geography and a slave to geopolitics. The threat from Azerbaijan, with Türkiye’s unprecedented military backing for Baku, has been a constant concern. Yet even after the 2020 war with Azerbaijan (and largely also because of that war), Armenia is now facing a new “Russia challenge,” rooted in the mistake of believing in Moscow’s security promises. In fact, as the military defeat in the 2020 war and the 2023 loss of Karabakh have painfully revealed to Armenia, Russia is an unreliable country, deceptively posing as a partner.

This combination of Russia’s abandonment of Armenia, or even complicity with Azerbaijan against Armenia, with the hollow expectations of security from the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), now clearly demonstrates that Yerevan stands alone. But this new painful Armenian reality has forged a new strategy for Armenia, seeking to “diversify” its security partners and allies.

For Armenia, this belated recognition of the limits of its “partnership” with Russia was not new, given Russia’s arrogant neglect of Armenia. In fact, Russia’s only consistency in its policy toward Armenia has been one of inattention, not intervention, and of distraction, not determination, as Moscow has long taken Yerevan for granted, with Armenia receiving few, if any, tangible benefits. Of course, the question of how far and how fast Armenia can move closer to the West is a strategically critical question.

As Armenia seeks to resist the “gravitational pull” of the “Russian orbit,” timing is essential for two reasons. First, there is a window of opportunity due to Russia’s continued distraction and overwhelm by its failed invasion of Ukraine. Second, there is a related opening for Armenia based on unprecedented Western (and European) interest in Armenia. In this context, Armenia is now viewed as a partner that is both a more reliable democracy and endowed with more strategic significance than before.

The key is not to try to “replace” Russia with the West but rather to offset Russia by diversifying security partners and allies.

However, the key is not to try to “replace” Russia with the West but rather to offset Russia by diversifying security partners and allies. This requires Armenia to adopt a more sophisticated transactional strategy and a policy approach of bartering and bargaining with both Moscow and the West. This is obviously a difficult and even dangerous challenge, but it is even more dangerous not to try.

Thus, the imperative for Armenia now centers on the need for strategic readjustment and reorientation. A pursuit of complementarity has long defined Armenian foreign policy as Yerevan sought a balance between its security partnership with Russia and its interest in deepening ties to the EU and the West. However, that policy has been difficult to maintain over the years, especially given the pre-existing trend of over-dependence on Russia. Obviously, Yerevan lacks the leverage to challenge Russia directly but can change the terms of that relationship. Armenian advantage comes from an endowment of increased strategic significance, a greater degree of stability and resilience, and a rare commodity of democratic legitimacy.

Currently, there is a rare opportunity for regional cooperation with the post-war geopolitical landscape in the South Caucasus, which offers a degree of promise over peril. More specifically, this opportunity for regional cooperation stems from the outlook for restoring regional trade and transport.

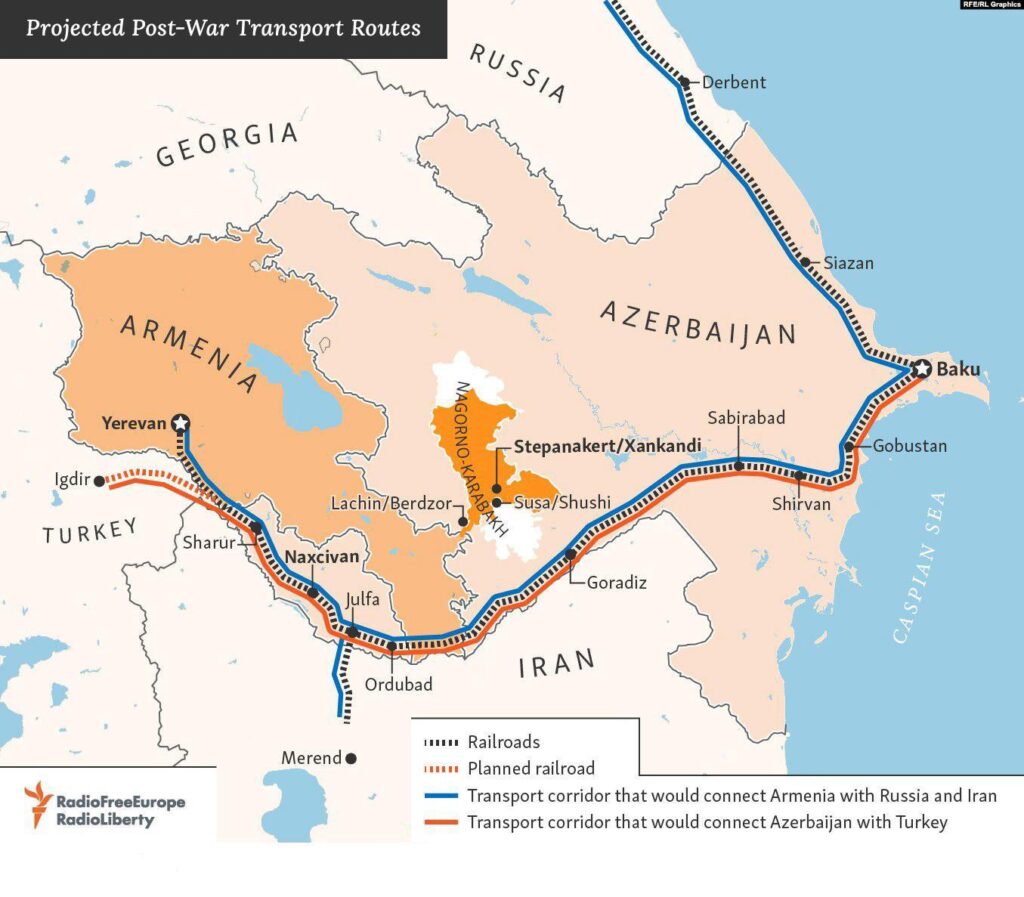

Negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, formally coordinated by Russia, have advanced in the work of a tripartite working group on regional trade and transport. More specifically, the working group’s negotiations resulted in an important preliminary agreement reiterating and reaffirming Armenian sovereignty over all road and railway links between Azerbaijan and its exclave, Nakhchivan, through southern Armenia. The successful agreement over the restoration of regional trade and transport is limited to the links between Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan as the first stage, however, with the planned reconstruction of the Soviet-era railway link and the construction of a highway through southern Armenia.

The broader second stage of regional trade and transport encompasses a more expansive and significantly more expensive strategy that includes the reopening of the closed border between Türkiye and Armenia and the restoration of the Soviet-era railway line between Kars and Gyumri as well as the eventual extension of the Azerbaijani railway network to allow Armenian rolling stock from southern Armenia in a north-eastern direction through Baku and on to southern Russia.

The issue of restoring regional trade and transport is significant as the only clear example of a “win-win” scenario for post-war stability with the economic and trade opportunities significant for all countries in the region.

The issue of restoring regional trade and transport is significant as the only clear example of a “win-win” scenario for post-war stability with the economic and trade opportunities significant for all countries in the region. It is also crucial to regain deterrence by forging economic interdependence to prevent renewed hostilities. In this way, financial incentives and trade opportunities have been elevated to a new and unprecedented degree of importance that has been long missing from the region.

Over the next few months, the post-war negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan are expected to accelerate in two core areas: border demarcation and the restoration of trade and transport. The primary driver for this acceleration of diplomatic engagement stems from two main factors. First, the Armenian concession over three border villages in late April offers a new precedent of a successful, albeit partial, restoration of a key dispute over border delineation. This will only encourage Azerbaijan to remain committed to the process of border demarcation talks, especially as Russia is now less of a direct manager of the talks.

A second promising sign is Azerbaijan’s move to lower its rhetoric and lessen its demands over the so-called “Zangezur Corridor.” For its part, Azerbaijan is no longer demanding “extraterritoriality” or any such weakening of Armenian sovereignty over the road and railway planned to traverse southern Armenia and give Azerbaijan access to its exclave of Nakhchivan.

Azerbaijan’s position continues to remain stubbornly maximalist, driven by domestic politics and defined by bellicose rhetoric.

Despite the likelihood of progress in the diplomatic negotiations, Azerbaijan’s position continues to remain stubbornly maximalist, driven by domestic politics and defined by bellicose rhetoric. This only suggests that Baku will seek to secure ever more concessions from Yerevan, imposing a punitive post-war peace on its own terms, thereby only increasing the insecurity and instability of the South Caucasus.