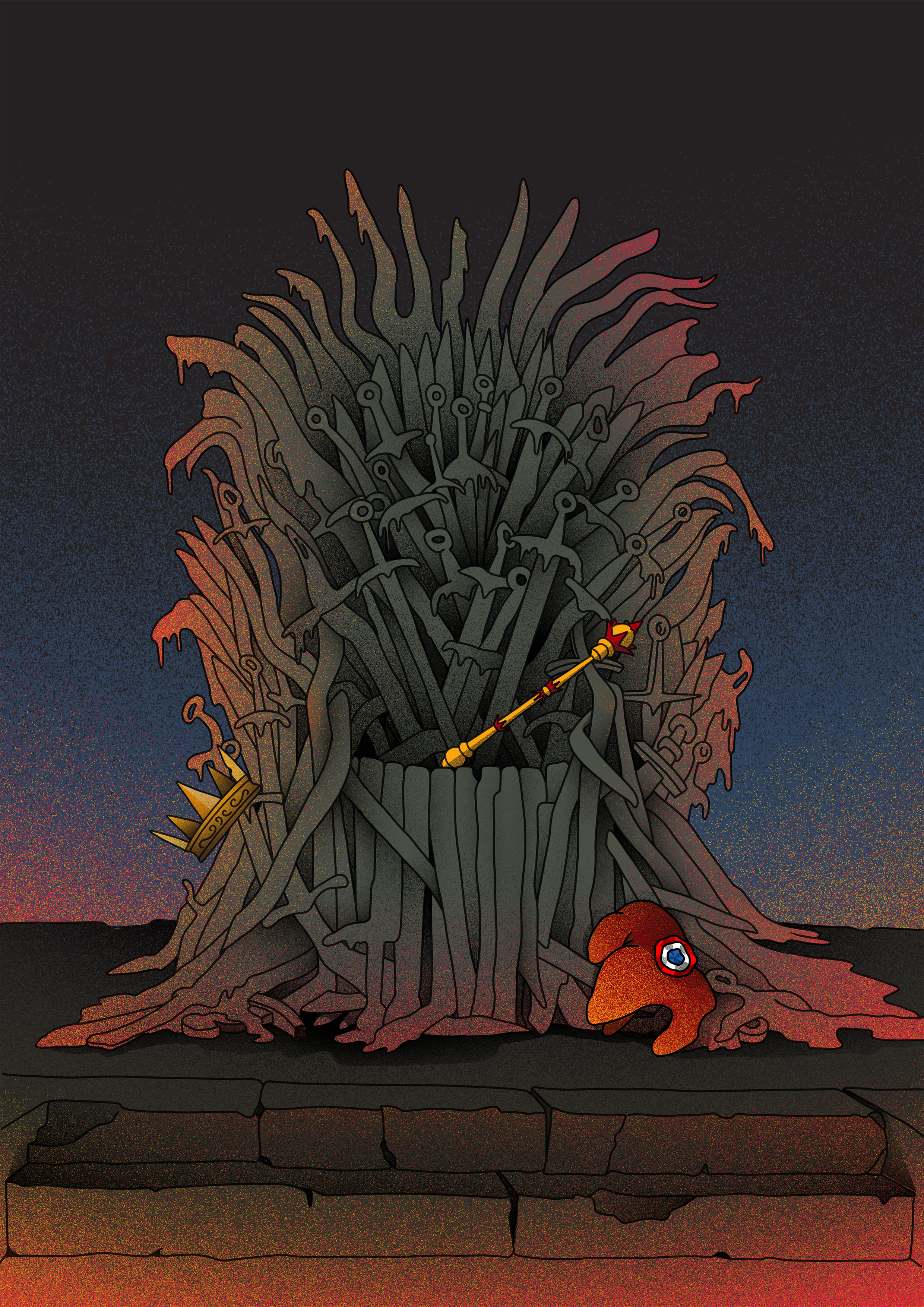

Autumn of the Sovereignist Patriarchs?

The annual Nations in Transit report by Freedom House, a watchdog, is a sobering read. In the context of re-emerging warfare, it paints a region stretching from Eastern Europe to Central Asia that is “being reordered by autocracy and democracy” and where “the countries caught between the two orders are coming to terms with the fact that there is no third option.”

Regimes that previously vacillated between democracy and autocracy—out of conviction or perceived expedience—are having a particularly hard time keeping their balancing act going.

I wrote back in 2016 that the “grey area” between consolidated democracies and autocratic Russia was particularly fertile ground for the oligarchs. They have learned to play by hybrid rules: knowing the Kremlin’s game, learning to show the democratic façade, and profiting from both. Figures like Bidzina Ivanishvili in Georgia or Vladimir Plahotniuc in Moldova embodied such leaders. Those “happy days” are now gone. Some, like Plahotniuc, stumbled on the scale of corruption and were overthrown through elections. Others also find it difficult to cling to, despite the temporary financial windfall profits the Western sanctions on Russia have created (even short of outright sanction-busting).

The Nations in Transit also found that to keep hold of power, most hybrid regimes have been growing more authoritarian in the past few years. That shift has been anchored in a somewhat eclectic political ideology that mixes the elements of reactionary conservatism, religious fundamentalism, and cultural nativism. It mixes those with a corrosive dollop of xenophobia and homophobia, stirring it up with conspiracy theories and fearmongering. This toxic mixture entices citizens to reject the universal applicability of liberal norms—human rights, freedom of speech, and assembly—as an external ploy to weaken their nation.

These “sovereign democracies” – Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Türkiye, and, increasingly, Georgia – with all their differences, quirks, and particularities, are sought-after travel companions for the Kremlin in its crusade against liberal Europe.

These “sovereign democracies” – Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Türkiye, and, increasingly, Georgia – with all their differences, quirks, and particularities, are sought-after travel companions for the Kremlin in its crusade against liberal Europe. What is worse, such ideology is resonating in Western Europe through a plethora of primarily ultra-right, anti-establishment parties. Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s strongman and one of the chief ideologues of the movement, promises to “occupy Brussels” in the upcoming 2024 European elections.

But recently, something has gone awry in the affairs of the autocratic leaders whose political longevity and economic prosperity seemed immutable.

Little Fires Everywhere

On 1 April 2024, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development (AK) party was dealt a severe blow by its chief rival, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), which swept local elections in big cities, including Istanbul. Even though the nationwide, overall score gave the opposition only a minimal margin, Erdoğan himself was forced to admit the event represented a “turning point” – a far cry from the bluster of 2019 when he called Istanbul election administration officials who gave victory to his party’s rival “idiots” and proceeded to crack down on opposition.

Erdoğan’s political ideology has never been liberal, but it took a particularly sinister turn after the failed 2016 coup, to which the AK responded with a monumental crackdown on all sorts of domestic opponents by arresting tens of thousands and purging hundreds of thousands from all walks of life, especially civil service. Despite, or thanks to, those strong-arm methods, the AK has consolidated power and, until recently, seemed unassailable.

This allowed Erdoğan to become a regional power player with no firm attachments, juggling his country’s traditional alliance with the US and its membership in NATO, arms supply deals with the Kremlin, readiness to accept a massive wave of Syrian refugees, assertive and even aggressive stance towards the European powers in the Aegean Sea, supply of deadly UAVs to Ukraine, and backdoor oil deals with Russia’s oil companies.

Yet, despite the attractiveness of such strongman politics in Türkiye and the rediscovery of Ankara’s traditional identity as a medium but critical power at the junction of the Occident and the Orient, the AK’s overall policies seem to have disappointed many Turks.

The sovereignist regimes live and die on the promise of predictability and stability.

The sovereignist regimes live and die on the promise of predictability and stability. Still, the unending economic troubles and the government’s much-criticized response to the 2023 earthquake have dented that premise. With the widening discussion about corruption and nepotism in AK ranks, the popularity of the democracy-minded opposition has also grown, especially under the new leadership. Some local analysts even say Erdoğan may respond to a crisis by scrapping the all-powerful executive presidency, fearful that it will fall into the hands of the opposition and bring back the parliamentary system.

Another patriarch of “sovereign democracy,” Viktor Orbán, also unexpectedly found himself in hot political water. Orbán’s Fidesz has been riding the wave of winning the fourth consecutive parliamentary term in 2022. More than once, it willingly set itself on a collision course with Brussels, effectively using the veto on aid to Ukraine to wrestle out financial aid despite stifling democratic institutions and the rule of law. With the political system, courts, and the media rigged to favor Fidesz, Orbán’s position also seemed rock-solid.

Yet, his highly socially conservative movement, which was purporting to protect children from the corrupting influence of “gay propaganda” and “gender politics,” blew up on a fast-burning child abuse scandal which led to the resignations of Hungary’s President and Justice Minister, both high-ranking Fidesz politicians.

As Orbán failed to contain the crisis, Péter Magyar, once an insider in the Fidesz party, emerged as a consolidating opposition figure. Tens of thousands of Hungarians—including from Fidesz’s traditional conservative electoral base—took to the streets demanding a change of government.

Add to this trend the political defenestration of Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party in the late 2023 elections by their longtime liberal rivals, and the outlook for Europe’s most established conservative and anti-liberal political forces suddenly looks less bright than often assumed. What is happening?

Choosing Your Camp

As the Freedom House report justly points out, in Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia, democratic regimes have coexisted with increasingly autocratic ones, leaving a range of grey areas: consolidating democracies and hybrid regimes. In Europe, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine projected a stark geopolitical shadow: there can be no middle ground between aggressive Russia and Europe.

In Europe, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine projected a stark geopolitical shadow: there can be no middle ground between aggressive Russia and Europe.

Before the war, the European Union plunged into the lethargy of “enlargement fatigue,” but after Russia invaded Ukraine, it opened its doors to Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. Implementing European governance standards was an obvious precondition for negotiations and eventual accession.

Orbán’s antics on Ukraine have exasperated the Western capitals. As a ranking member of the German Parliament remarked recently, “the prospect of another Orbán-like regime will lower the chances of […] joining the European Union down to zero.”

On its side, Russia is on a war footing, and more than ever, the thuggish inhabitants of the Kremlin demand and value unquestioned loyalty above all. The demise of the top warlord, Evgeni Prigozhin, showed that even Putin’s personal, valuable cronies could not play the “Tsar is Good, but the Boyars are Bad” card to gain more influence.

These days, Russia demands undiluted loyalty in the form of legislative shibboleths, such as the “foreign agent laws,” be it in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Republika Srpska or Georgia which work to bring the repressive powers of the overbearing state into sync with Russia’s repressive laws.

So, what lessons are from Türkiye, Hungary, and Poland? Which way are things going?

People tire of authoritarian populists, too.

First lesson: People tire of authoritarian populists, too. Their speeches lose luster, their promises ring hollow, and once the economy hits the doldrums or abuses of power become too apparent and outrageous, voters seek new champions.

The regimes that have stacked all the cards against the opposition are vulnerable if they are left standing in the real vestiges of electoral democracy.

Second, even the regimes that have stacked all the cards against the opposition are vulnerable if they are left standing in the real vestiges of electoral democracy. You may designate the opposition and quash it through repression (like in Türkiye), ruse (like in Hungary), or legislative capture of the key institutions (like in Poland or Moldova), but the old forces can re-consolidate (like in Moldova, Poland, and Türkiye), and the new ones may emerge, often from inside the regime (like in Hungary).

So far, it is promising for the partisans of the liberal worldview and democracy. But not so fast.

Institutional capture and the dominance of security institutions leave ample space for autocratic leaders to quell and turn the tide of opposition.

Thirdly, institutional capture and the dominance of security institutions leave ample space for autocratic leaders to quell and turn the tide of opposition. Adam Bodnar, the Polish justice minister tasked with restoring the independence of the judiciary, said recently that the task is “colossal,” and once captured, these institutions are hellishly difficult to revert to normal while staying within the confines of the Constitutional order. Similarly, Moldova finds it hard to shed the vestiges of state capture, especially in the justice sector, left over by the oligarchic rule. The challenge seems daunting for Hungary as well, where Fidesz has been gnawing at the institutional foundations of democracy longer, or Türkiye and Georgia, where they have not been fully consolidated to begin with.

Being under the Western/NATO security umbrella makes it easier – if not inevitable – to make a pro-democratic choice.

Fourth, security plays a significant role: being under the Western/NATO security umbrella makes it easier – if not inevitable – to make a pro-democratic choice. Being left outside such an umbrella exposes one to the whims and wrath of unchained authoritarian powers, making choices ever starker. This augurs ill for Ukraine and Georgia. Also, obviously, the larger the country is – in terms of its territorial and population, but mostly its geopolitical weight – the larger its freedom of maneuver and range of choices.

Fifth, in-country choices are closely tied to regional and international trends. Citizens are not passive actors but perceive the stark choices before them. A choice towards autocracy is often a choice for stability and based on the fear of a catastrophe, such as war, civil strife, and economic collapse, whether conscious or unconscious, real or manipulated.

A resounding success of Western support for Ukraine will convince many that liberal democracies are indeed capable of self-defense and are less of a risky proposition than the leaders led them to believe.

A resounding success of Western support for Ukraine will convince many that liberal democracies are indeed capable of self-defense and are less of a risky proposition than the leaders led them to believe. The longer the current penury of Western aid leaves Ukraine defenseless against the Russian onslaught, the weightier the Russian menace and the more tempting it is to submit to its diktat.

Finally, although the Nations in Transit report shows that the established Western European democracies have been consolidating, we face years of crucial elections. The success of the sovereignist, anti-liberal political forces in the US, France, and Germany will put in the sails of their eastern and southern precursors. And even if one populist strongman stumbles, another will take his place.

Time for Stark Choices

War in Europe is a harbinger of ideological polarization both within the countries and between the emerging camps. As the grey zones shrink, citizens face stark choices. Their ability to make those choices is not equal in every country. While Western Europeans will choose their leaders freely, in Europe’s east and southern neighborhoods, they would first have to counter the gravity field created by anti-liberal forces and autocratic regional powers.

Recent developments show that democracy retains its rallying force of attraction even in places where populist sovereignism has captured politics – and state institutions - for decades. Citizens band together, sometimes across the political divide, to make their voices heard and to restore a functioning democratic institution. People in Ukraine make advances in their democratic institutions, even as they wage an existential war against revisionist Russia.

In 2024, Europeans who live in democracies will make a choice: either to stand in solidarity with their brave neighbors and thus expand the field of attraction of the freedom-loving pole or to go into a fatal lockdown against the rising tide of authoritarianism. Nothing is decided yet.