The Power of the Purse: How Money Saved Ivanishvili’s Regime

The recent rifts within the Georgian Dream may not seem to threaten the regime’s edifice, but they serve as indicators of fault lines of the system that billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili has erected to protect and advance his interests.

On 28 November 2024, Georgian Dream Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced that Tbilisi was unilaterally suspending talks on joining the European Union, drawing a mix of confusion and outrage across the political spectrum. The statement seemed not only ill-timed but also miscalculated. After all, he was speaking to a public where pro-European sentiment is deeply embedded in the national psyche; a memory of several popular uprisings, all driven by aspirations for democratic reforms and alignment with the West.

Yet, the Georgian Dream managed to survive the twin crises of domestic backlash and international condemnation.

So, what explains the system’s resilience? Has the public become less enthusiastic about the concept of democracy and European integration? Or have the authorities become more adept at suppressing dissent? There may be some truth to both, but neither fully accounts for what we are witnessing in Tbilisi.

For most of its post-independence history, politics in Georgia has been as much about the economy as about democracy, human rights, and foreign policy orientation. But much like in previous times, the economy does not receive the attention it deserves in the mainstream political analysis of recent developments.

To understand why the Georgian Dream survived, we need to follow the money.

So, to understand why the Georgian Dream survived, we need to follow the money. And to follow the money, we must untangle a complex and increasingly opaque web of relations between political leaders, informal figures, and business elites – a system shaped and sustained under the shadow of Bidzina Ivanishvili, the oligarch whose influence continues to define Georgia’s political landscape of the last 13 years.

State-Business Relations in Georgia

In the early 1990s, Georgia’s economy was more a casualty of politics than its driver. Internal conflicts and the collapse of state institutions left the country’s economy in shambles. The GDP collapsed by nearly two-thirds from 1991 to 1993, one of the most dramatic contractions in contemporary history. A recovery around 1995 relied on classical fiscal tightening and privatization, backed by international financial institutions. Georgia also became a node in hydrocarbon pipeline projects aimed at linking Türkiye and Europe with the Caspian region. But entrenched corruption, coupled with organized crime and weak governance, undercut growth and social recovery. Severe budget deficits, unpaid wages, and soaring unemployment remained unaddressed.

Ultimately, public discontent with Eduard Shevardnadze's political and economic policies led to the Rose Revolution of 2003, ushering in a team of young reformists under the leadership of former President Mikheil Saakashvili. Inspired by free market ideology, Saakashvili’s government launched an aggressive campaign against corruption, simultaneously reducing administrative burdens and minimizing the state’s role in the economy. The nimbler, less corrupt government and investor-friendly rules spurred GDP growth and budgetary revenues, although the benefits were slow to trickle down to the broader public. Still, Georgia demonstrated remarkable agility in recovering from both the Russian embargo of 2006 and the Russian invasion of 2008.

But with more money came the temptation to leverage it for political purposes. Numerous accounts from the early years of Saakashvili’s administration indicate that funds were extracted from businesses. At the same time, later, companies were reportedly pressured to finance specific infrastructure or social projects. Others were directly co-opted by the authorities, offering preferential access to economic opportunities in exchange for political loyalty and generous pre-election endowments.

The year 2012 witnessed the first-ever orderly democratic transition and held promise, including in the economy. Although the central tenets of Georgia’s economic policy, such as trade liberalization and bureaucratic simplification, remained in place, the Georgian Dream adopted more socially oriented policies. Several large-scale social spending programs were enacted, particularly in healthcare and education, financed in part by cuts in the defense budget, increased Western financial support, and a revival of trade with Russia, which had dropped to near zero following the 2006 embargo and the 2008 invasion. This shift (but also perhaps earlier improvements in the quality of healthcare) yielded some results – mortality rates declined, and the quality of life improved for some segments of the population. Still, the GDP grew at a moderate pace and rising expenditures, combined with external shocks in the mid-2010s, led to a significant depreciation of the national currency.

By the time COVID-19 hit, these pressures were largely offset by revenues from tourism, exports, and services, particularly in the transport and logistics sectors. In parallel, Georgia continued to reap the benefits of free trade agreements, concluded first with the EU and later with China. The opening of visa-free travel to the Schengen Area had a positive effect as well, boosting remittance inflows from Georgians working in the European Union. No less important was the sustained financial support from the West. In short, although there were no significant economic leaps forward in the first decade of the Georgian Dream administration, there was also no significant worsening.

In politics, this meant there were no strong forces for change. The large-scale social spending created the impression that the authorities were responsive to public needs. A gentleman’s agreement gradually took hold – one in which the state was expected to address basic social needs while largely stepping back from interfering in private enterprise, at least in most cases. This arrangement suited business circles well. For many in the business community, the new rules of the game seemed less intrusive; the state no longer coerced businesses into funding favored projects and the overall trajectory seemed more predictable, they argued.

Underneath It All

The foundational elements of big business-state relations leaned further into political and crony favoritism, exemplified by lucrative public procurement contracts to well-connected firms, often with close links to Ivanishvili’s inner circle.

Behind the formal façade, however, some of the uglier elements of the political economy of power were retained and even expanded. The foundational elements of big business-state relations leaned further into political and crony favoritism, exemplified by lucrative public procurement contracts to well-connected firms, often with close links to Ivanishvili’s inner circle. The revolving door between politics and business also widened, especially for former officials from law enforcement. Similarly, the practice of political donations in exchange for protection or economic advantages persisted and grew even stronger.

But while the underlying transactional dynamics remained intact, one key difference emerged: Georgia now had a leader who was not merely a politician balancing among competing business circles, but a business actor himself. And like leaders of his stamp, Ivanishvili had a direct stake in the economy—a significant departure from all three of Georgia’s post-independence leaders and also a marked contrast from the so-called “illiberal” European leaders, such as Viktor Orbán or Aleksandar Vučić.

Importantly, Ivanishvili was also backed by his vast personal wealth, which insulated him from domestic political pressures to an extent unimaginable for all previous Georgian leaders. This meant that Ivanishvili could buy his way through the usual constraints of electoral politics. He made this very clear on several occasions – first in the 2018 elections, when the ruling party’s favorite, Salome Zourabichvili, came close to losing a race against the opponent, and then in 2020, when the opposition fielded an effective campaign against the Georgian Dream. To reverse the tide, Ivanishvili intervened directly, pouring millions into the campaigns to secure victory for his party.

On most other occasions, however, it was not Ivanishvili but his lieutenants who were expected to chip in, including in financing the Georgian Dream’s propaganda machinery, satellite political parties, and a network of loyal commentators. In other words, the oligarch was very prudent in staking his own money into political control, preferring the role of the lender of last resort, rather than the primary financier.

For Ivanishvili, controlling Georgia was much more than a profit-making opportunity or an occasional diversion. What Georgia offered was much bigger - it lent a convenient sovereign shield for his assets.

But for Ivanishvili, controlling Georgia was much more than a profit-making opportunity or an occasional diversion. What Georgia offered was much bigger - it lent a convenient sovereign shield for his assets. So, when a rogue Credit Suisse trader swindled Ivanishvili in an illicit investment scheme, and he came to see it as a malevolent conspiracy masterminded by the West to oust him from power, Ivanishvili began a dangerous game of brinkmanship with the West, signaling that he was willing to leverage the country’s foreign policy orientation unless his money was fully and unconditionally recovered.

By 2020, the Georgian Dream had gained relative stability as a monolithic party of power, overcoming internal differences and capturing nearly all state institutions. The Georgian Dream also managed to retain a façade of international respectability.

But Russia’s invasion in Ukraine has upset this status quo in several important ways.

Stress Test of Ukraine

When Georgian authorities refrained from adopting economic sanctions against Russia – and instead deepened their ties with Moscow – many were taken aback. How could a society that had experienced similar aggression appear so indifferent to its Ukrainian peers, they asked. How could a staunch Western ally remain silent in the face of Russian brutality, others echoed the sentiment. But the reality was that this was no longer about historical memory, shared trauma, or foreign policy orientation.

Georgia met the Russian invasion of Ukraine not with solidarity but with the logic of a deeply clientelist, rent-oriented system – one in which state institutions were routinely leveraged to serve the interests of a single individual and his inner circle; with a system where political loyalty was sustained not through genuine redistribution but through large-scale social spending and co-optation of business elites. Importantly, this was a country whose leadership understood (and shared) the mentality and business interests of the Russian elite.

The overwhelming support of the majority of Georgians to the Ukrainian cause, or the fresh memories of the Russian invasion, mattered little compared to financial gains. What mattered was money and regime survival.

This was also a system in which the basic principles of democratic accountability had long been broken down. As a result, the overwhelming support of the majority of Georgians to the Ukrainian cause, or the fresh memories of the Russian invasion, mattered little compared to financial gains. What mattered was money and regime survival.

Seen through this lens, the Georgian Dream’s reaction was hardly surprising – on the contrary, it was entirely logical. They saw the war as an opportunity to profit and seized it without hesitation or regard to morality.

And they opened the gates to the Russians.

Cut off from the rest of Europe, tens of thousands of Russians flocked to Georgia. In 2022 alone, 62,304 Russians entered and remained in the country; in 2023, the corresponding number was 52,627. Georgia proved particularly appealing – and welcoming – for Russians. Its liberal residency requirements allowed them to stay for a year or longer, while its banks made it possible to access the global financial market.

The benefits seemed mutual. Fearing collapse in their banking system, Russians relocated their assets to Georgia – bringing more than two billion USD only in 2022, a fourfold increase as compared to the previous year. They rented or purchased houses and apartments, boosting the real estate sector. They also started businesses. In that year alone, Russians established 11,000 new enterprises, mostly in the IT sector.

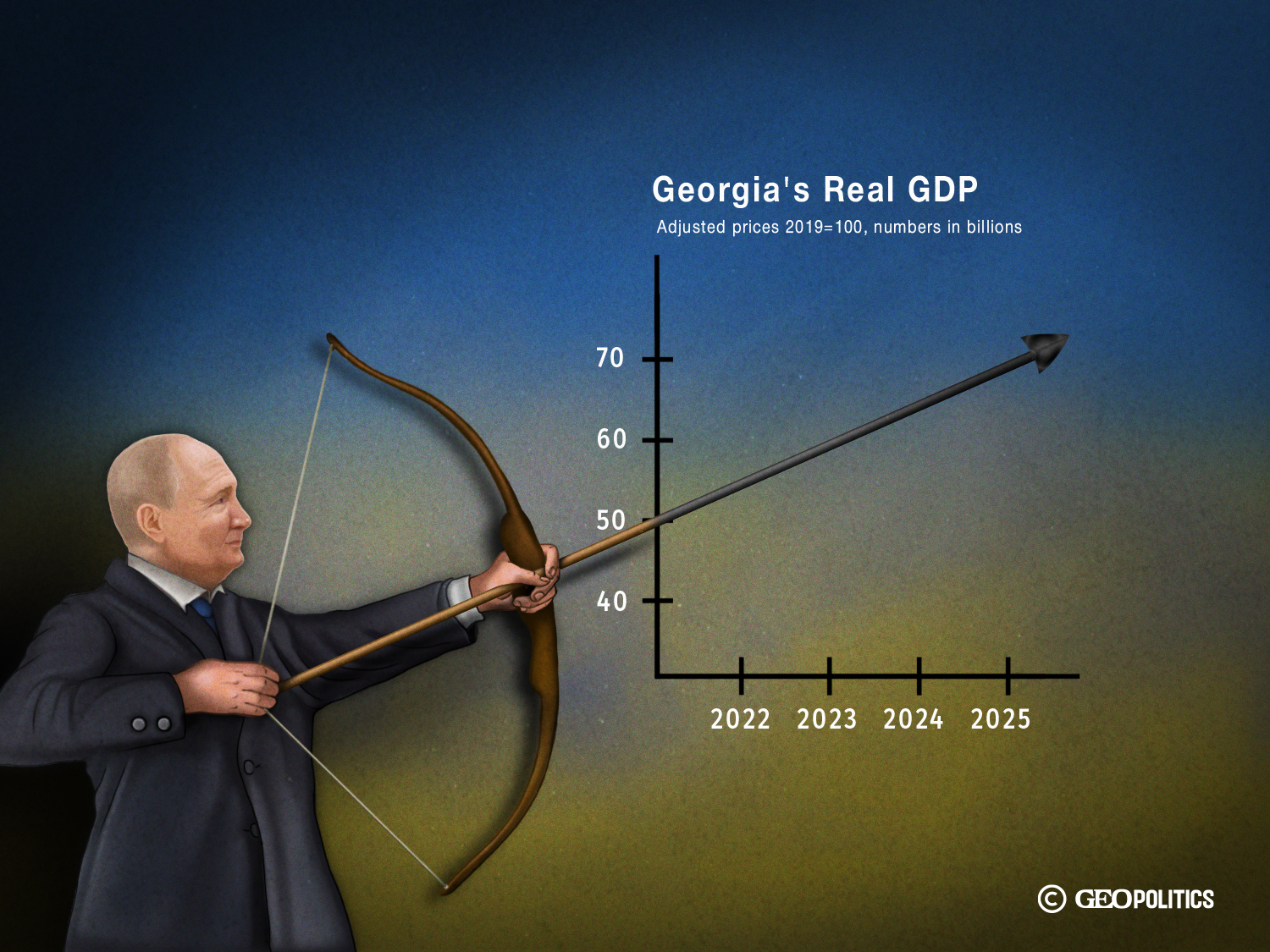

In parallel, trade and cargo transit increased. The air traffic resumed in May 2023, despite opposition from Europe, followed by Moscow lifting visa requirements for Georgian nationals. All of this played a significant role in the increased economic output in Georgia. As a result, in 2022, the economy grew by 10.4%. In 2023, the number stood at 7.8%, and in 2024, the country registered a 9.4% GDP growth.

While no official accounts provide evidence of outright sanctions evasion, numerous reports indicate that post-invasion trade has operated in a legal gray zone.

But there is much more to the story than transactional post-Soviet government and business elites piggybacking on new economic opportunities. While no official accounts provide evidence of outright sanctions evasion, numerous reports indicate that post-invasion trade has operated in a legal gray zone.

Over the past three years, Georgia’s trade volumes have increased across several commodities, including cars, electronics, and other consumer goods. While trade turnover with Russia has remained relatively stable since the invasion, exports to third countries have surged. One report indicates that exports to Armenia increased by 128% from 2022 to 2023, while those to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan rose by 201% and 148%, respectively. This suggests that the country has been enabling the flow of goods into Russia.

The re-export of automobiles to Russia is a case in point here.

Since the outbreak of the full-scale war, Georgia has become a key transit corridor for vehicle trade. Brought by sea into Georgia from Europe and the United States, cars are exported either directly to Russia or via Armenia, Kazakhstan, or Kyrgyzstan, where they are first cleared for customs within the Eurasian Economic Union and then sent to their final destination in Russia. According to Geostat, Georgia’s national statistics office, car exports from Georgia increased from USD 0.5 billion in 2021 to USD 2.4 billion in 2024.

Recent investigative work by Georgian journalists has also suggested that the country is used as an intermediary for exporting dual-use items to Russia, both directly and through third countries. These include electronic devices, such as radio navigation equipment, routers, processors, and recorders – all of which are fit for military purposes and are banned by Western sanctions.

The import of oil and petroleum products from Russia has also increased, from USD 0.8 billion in 2021 to USD 1.3 billion in 2024, leading some observers to suggest that Georgia may be circumventing the sanctions regime by reselling oil (a commodity the country produces in only modest amounts) to Europe.

Money, Elections, and Pivot from the West

Despite consistent economic growth, the increase did not translate into improved well-being for large segments of the population. On the contrary, with a large migratory influx, property prices soared and most Georgians continued to grapple with rising inflation. Indeed, a recent survey found that 81% of Georgians believe their economic conditions have either remained the same or worsened over the past three years.

During the 2024 election campaign, the party captains reportedly threatened voters that they would lose these benefits if they voted against the Georgian Dream.

Still, additional windfall profits allowed the authorities the freedom of lavish social spending. For instance, from 2021 to 2024, the number of subsistence allowance beneficiaries increased from 587,524 to 671,337, to nearly one-fifth of the electorate. As the already weak differentiation between the state and the ruling party effectively vanished, this spending was leveraged for electoral gain, giving the ruling party an unfair advantage. In the lead-up to the October 2024 elections, the Georgian Dream also introduced a range of additional state-funded programs, including debt forgiveness schemes, public employment initiatives, and salary increases for civil servants. During the 2024 election campaign, the party captains reportedly threatened voters that they would lose these benefits if they voted against the Georgian Dream.

The new geopolitical landscape gave the ruling party additional confidence. A key factor was the closure of the Northern Corridor – China’s traditional overland trade route to Europe. Georgia, as an element of the Middle Corridor, an alternative trade route project connecting China to Europe, found itself not only economically stronger but also more strategically important. Tbilisi’s standing was further enhanced by discussions on an underwater electricity cable linking Azerbaijan, Georgia, Romania, and Hungary. The EU’s interest in these two projects – and by extension, Georgia's role within them – gave Tbilisi an impression of becoming indispensable. “Europe needs Georgia as much as Georgia needs Europe,” the Georgian Dream’s leaders argued with self-assurance.

Increased revenues from alternative sources, beyond traditional Europe-bound trade, allowed Ivanishvili to hedge his positions against potential economic repercussions of worsened relations with Europe. At the same time, the new geopolitical constellation fostered a sense of geopolitical impunity. At the same time, the ideology of mortal confrontation with the West and fears of lurking conspiracy have permeated his mindset, likely reinforced through communication with Moscow circles who pride themselves on knowing “what is really happening.”

Tightening the Regime

This new constellation played out particularly negatively for Georgian democracy. War profits emboldened the ruling party, prompting more aggressive actions against dissenting voices and strengthening the tendency to downplay – if not outright dismiss – external concerns over democratic deterioration. As a result, the Georgian Dream’s authoritarian drift accelerated.

Demonstrating Ivanishvili's pattern of thinking as primarily an economic actor, the party went after money - specifically, the sources financing resistance to the regime. Laws targeting foreign support to civil society and media were rubber-stamped by the Parliament one after another.

Beyond ideological virtue signaling to Moscow, the stack of legislation served to undercut the only financial flows over which Ivanishvili had no control. This proved particularly painful for civil society. Compounded by the withdrawal of USAID and a general drop in aid budgets in European states as they rearm and support Ukraine, organized civil society groups have found themselves operating in a survival mode.

Simultaneously, the Georgian Dream moved to choke the protest financially, issuing fines for alleged violations of protest legislation at an unprecedented scale and frequency. The middle class, which has been driving the protests, found its economic base stretched to the limit while business elites sympathetic to the movement exercised caution, opting to make decisions based on market instincts rather than values and principles.

Pro-democracy protesters have found themselves fighting an uphill battle – fighting for their survival while challenging a government that is not only repressive but increasingly propped up by revenues from murky trade flows between Russia and the West.

As a result, pro-democracy protesters have found themselves fighting an uphill battle – fighting for their survival while challenging a government that is not only repressive but increasingly propped up by revenues from murky trade flows between Russia and the West.

The Going Gets Tough

Excessive violence and financial terror against citizens did not cancel the protest. On the contrary, it widened rifts among the Georgian Dream’s high-ups, prompted mid-level defections, and eroded overall support.

Even though things seem to be going well for the Georgian Dream in many ways, worrying signs also abound. Its authoritarian slide was met with more resistance at home than their leaders expected. Excessive violence and financial terror against citizens did not cancel the protest. On the contrary, it widened rifts among the Georgian Dream’s high-ups, prompted mid-level defections, and eroded overall support. A reset with the U.S., fueled by the election of Donald Trump (undoubtedly murmured by Muscovite elites into the Georgian Dream leader’s ears), did not occur either.

Threatened by sanctions, Ivanishvili rushed to repatriate his assets, a move that is significant on two levels. Not only did it expose his vulnerability to external political shocks, it also highlighted how closely his wealth is interlinked with Georgian politics. More worryingly, it also signaled how reliant Ivanishvili has become on maintaining political control in Tbilisi – ruling Georgia was once just a profitable convenience when the billionaire had the luxury of leaving wherever and whenever he pleased. Now, a threat to his power in Georgia could prove much costlier.

Profits from Russian immigration have also dwindled as Moscow found larger economic partners and put its economy on a war footing. This, combined with domestic instability and confrontation with the West, seems to have strained Georgian Dream coffers enough for Ivanishvili to call in some of his earlier investments. And as Vladimir Putin found at the outset of the war, his Georgian counterpart came to realize that some of his henchmen had pilfered and could not repay. The large wave of purges currently taking place under Irakli Kobakhidze’s watch, including the mysterious shooting incident involving the former head of the Adjara government, Tornike Rizhvadze, and the seemingly routine discovery of a firearm in the travel suitcase of a prominent Georgian businessman, appears to fit this pattern all too well.

Looking Ahead

Seeing through this light, Georgia's immediate future is played out in bank accounts as much as it is in the streets of Tbilisi and elsewhere. The Georgian Dream might have carried the torch unchallenged until this day, but its model of politico-economic governance – rooted in clientelism and underpinned by general fiscal laxity – is also hitting its limits. Georgia may continue to benefit – by inertia – from being a comfortable zone through which the opponents trade, legally or less so, but a sanctioned hardline regime in a domestic crisis of legitimacy cannot perform this function for long.

Moving forward, Ivanishvili could make a step towards compromise with the West and the domestic opposition or inject his own money in order to stabilize the authoritarian system. But for that, he would need much more visible, personal, and direct control.

Are current purges a sign of dawning personalized autocracy? This may well be, but without underpinning natural resources or personal political charisma to proffer it, such a regime is likely to be very brittle.