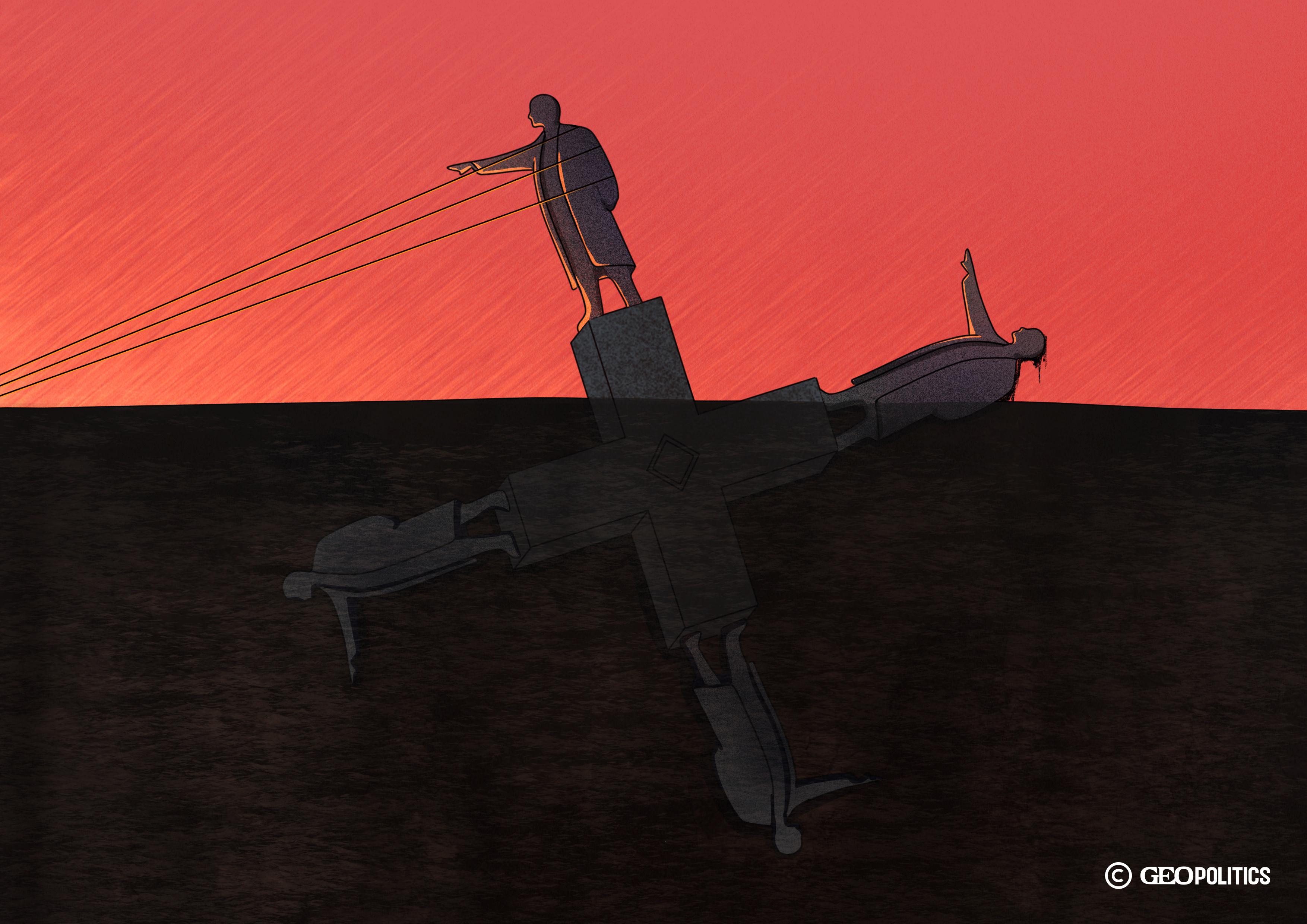

Empire vs. Republic: A New Hope

In January 1921, just a month before the Red Army seized Tbilisi, Georgian authorities announced the arrest of 513 Bolshevik-Communists, including foreign agents and members of the local Communist Party. An official report from the Special Detachment (Security and Counterintelligence Service) to the Minister of the Interior detailed how these individuals had been secretly working to undermine the Georgian state and its democratic order. They had gathered and distributed weapons to hostile groups, passed on classified military and civil information, spread propaganda, circulated funds to incite unrest, and engaged in other covert activities aimed at destabilizing the republic. Over a century ago, Georgian intelligence successfully exposed and dismantled this vast network of anti-state conspirators, halting Russia’s subversive operations—yet within weeks, brute military force crushed the fledgling Georgian state.

When the Georgian Democratic Republic was established in 1918, the aftermath of World War I was still being addressed. The young republic, led by the Social Democratic Party, which enjoyed widespread popularity, was facing existential threats from multiple directions. The military frontline was stabilized quickly. First, Germany helped by controlling its Ottoman allies and then the Entente powers. However, the threat from the former imperial patron, the Russian Empire, persisted.

In fact, until 1920, Georgia had to deal with not just one but at least two Russias. The Volunteer Army of General Anton Denikin exercised control over the North Caucasus and the northwestern shores of Georgia's Black Sea border. Denikin's primary objective was the restoration of the Russian Empire, and he regarded the existence of an independent Georgia as a temporary anomaly. However, his primary concern was to challenge the Bolshevik regime in Russia itself and later, to resist the onslaught of the Red Army led by Leon Trotsky. The Russian civil war had created a challenging security environment for Georgia, particularly given the continued instability along its northern borders.

The republic fell due to a military invasion, yet the "fighters of the invisible front" achieved notable victories in countering and mitigating the Russian threat. These lessons remain applicable in modern times as well.

Georgia established diverse security services to address these threats while the political leadership prioritized resilience. Ultimately, the republic fell due to a military invasion, yet the "fighters of the invisible front" achieved notable victories in countering and mitigating the Russian threat. These lessons remain applicable in modern times as well.

Ideological Coherence Enhances Resilience

Georgia's nascent security services were operational even before the establishment of the republic. Following the Bolshevik coup in Russia, the imperial army disbanded. The command system had largely collapsed. Bolshevik sympathizers were numerous in the Tbilisi garrison of the troops, creating a credible threat of a coup that would capture the erstwhile capital of the Russian "Transcaucasian" provinces. On 12 December 1917, following a tip-off from intelligence sources, 250 fighters from the Public Security Commission proceeded to disarm the Tbilisi garrison and seize armaments. This decisive victory prevented the Bolsheviks from immediately seizing control of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The fighters, primarily Social-Democratic militants led by Valiko Jugheli, became the core of the National Guard, an armed people's militia largely created along party lines.

The ideological coherence of the National Guard and their visceral resentment of the Bolsheviks made them the most resilient security formations in the early days of the republic, when its police and army were still in infancy. Jugheli, who had previously engaged with Bolshevism before rejoining the Social Democrats, had a deep understanding of his opponents and their methods. This allowed him to predict and preempt their actions, giving him a significant advantage. Beginning in 1918, the National Guard played a pivotal role in quelling Bolshevik-inspired riots and rebellions in multiple provinces and towns across the country.

Gogita Paghava, a young delegate of the Constituent Assembly from the Social Democratic Party, was soon appointed to the position of Head of the Information Department of the National Guard Headquarters. He was the emerging leader within the Georgian intelligence services, demonstrating a high level of proficiency in establishing and sustaining networks of assets throughout Georgia as well as in the North Caucasus and the Ottoman Empire. In this case, ideological proximity and loyalty proved to be the primary factors contributing to cohesion.

This coherence is evident in the strategic roles often assumed by National Guard personnel during the planning and execution of intelligence operations against the Soviet regime while in exile.

Institutional Memory - An Invaluable Asset

The National Guard of the First Republic was a quasi-military formation with intelligence components that played a role in stabilizing the security situation. However, in (relative) peacetime, the primary responsibility of counterintelligence fell to investigative and police functions. By mid-1919, the Bolsheviks and Denikin's army had shifted their focus to undermining and sabotaging the government in Tbilisi with the aim of destabilizing it. This task required a different approach, a longer-term perspective, and diligent sleuthing.

The former Imperial security officers' extensive experience proved invaluable in this regard, although they were subject to strict oversight from the executive. The People's Militia, also known as the police force, was established under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, led by Noe Ramishvili, a highly skilled administrator and a prominent figure in the political arena. Following the Social Democratic Party's vision, standard policing functions were transferred to local and city self-governments as soon as they were established. The Ministry of the Interior retained the functions of general coordination and training.

However, when it came to combating organized crime and counterintelligence operations, these units were strategically positioned at the core of the Ministry. The "Special Detachment" was established in the summer of 1918. Melkisedek Kedia, a former Gendarmerie officer, had been appointed to the command position. In close coordination with the Special Detachment of the Criminal Militia, which also oversaw the rapid reaction units, the Special Detachment's influence expanded significantly. Initially comprising 20 officers and 40 line militiamen, it doubled in size by 1920.

The "Specials" had a significant advantage in this regard, having maintained a substantial network of informers and agents from the times of the Russian Empire. Given their previous service to the Tsars, these individuals rightly viewed the Bolsheviks with greater concern than the Social Democrats, their declared adversaries. Therefore, in regions facing an imminent Bolshevik threat, the Special Detachment had an extensive network that extended deep into Russian territory, particularly in the North Caucasus via Vladikavkaz, which boasted a substantial and well-established Georgian community.

In the Georgian government's efforts to counter Denikin's army, there were instances of agents demonstrating allegiances that were not necessarily aligned with the Georgian side. Kedia's team relied on networks within the left-wing movements, sometimes including the Bolshevik faction, as well as local nationalist movements. The former Bolshevik field commander of the National Guard, Valiko Jugheli, was able to tap into these networks easily.

Diversity of Services – Assets and Risks

The National Guard and the Special Detachment were undoubtedly setting the standard. In addition, the Army headquarters’ intelligence department was responsible for handling military classified information and counterintelligence.

The National Guard demonstrated the most significant ideological coherence and loyalty to the government, making it the most difficult unit for adversaries to infiltrate.

The diversity of the Georgian security services contributed to their resilience as they leveraged various networks and were able to withstand certain threats more effectively than others, thereby fostering a sense of complementarity. The National Guard demonstrated the most significant ideological coherence and loyalty to the government, making it the most difficult unit for adversaries to infiltrate. The Special Detachment was the most professional and capable of exploiting human intelligence networks more extensively for counterintelligence. The Army intelligence unit was particularly susceptible to infiltration by former comrades-in-arms, namely Tsarist army officers. Many of these officers had served on Denikin's side and subsequently joined the Red Army. However, they were staunchly anti-Communist and sought to enlist their former comrades who had joined the Red Army under duress rather than out of personal conviction. This vulnerability proved advantageous in the Army's efforts to recruit a robust network at the points of contact with the Red Army in the North Caucasus in 1920. This network provided crucial intelligence, enabling the Army to receive advance warning of operations.

The National Guard commander was skeptical of the Army and did not fully trust the Special Detachment's Gendarmerie cadre. However, he had a positive relationship with the Minister of the Interior, whom the party had appointed. This enabled two services to work closely together. Notably, following his emigration, Giorgi Paghava assumed command of the Special Detachment, which subsequently provided crucial intelligence to Allied forces, offering vital insights into Russian and later Soviet activities in the occupied South Caucasus region.

The efforts of Georgia's security services proved to be a swift success. By August-September 1919, clandestine Bolshevik cells had been largely dismantled, with many of their members arrested or deported to Russia. In May 1920, a treaty was concluded with the Soviet Union, recognizing Georgia's sovereignty and establishing its northern border. According to the terms of the treaty, Tbilisi committed to reinstating the Georgian Communist Party, contingent on their acknowledgement of Georgia's legal framework and Tbilisi's authority. However, within a matter of months, the majority of Georgian Bolsheviks were once again forced to flee, resulting in the disruption of their operational cells.

At the onset of the Red Army's offensive in early 1921, no party cell, not even a single member of the Communist Party, had any prior awareness of the attack in Georgia. This is known from a classified report by Philipe Makharadze, the Communist Party chief and a senior executive in occupied Georgia, to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party. The report was sent on 6 December 1921. The report was intercepted by Georgian intelligence and subsequently published in the émigré newspaper, Free Georgia. Makharadze stated that the success of Georgian intelligence was detrimental to the interests of the Soviets. He explained that the entry of the Red Army and the declaration of Soviet rule were clearly perceived as an external conquest because Georgian communists did not consider an uprising. A failure to portray the intervention as "liberation" in the early stages led to a loss of crucial legitimacy for the new power.

Primary Vectors of Russian Pressure

Georgia selected Germany as its primary ally while the Volunteer Army aligned more closely with the United Kingdom and the Entente powers. The eventual victory of the Entente powers could have potentially undermined Georgia.

Russia had several ways of exerting pressure on Georgia during the First Republic. Denikin's army did not support the Georgian independence movement and was prepared to use force to suppress it if necessary. For the Volunteer Army HQ, the legal continuity of the Russian Empire after the Bolshevik coup, as well as Georgian statehood and government, was illegitimate. In the early days of the Republic's formation, the global landscape was favorable to Denikin. Georgia selected Germany as its primary ally while the Volunteer Army aligned more closely with the United Kingdom and the Entente powers. The eventual victory of the Entente powers could have potentially undermined Georgia. However, the Bolsheviks were exerting pressure on Denikin's army while the Georgian National Guard and army were taking every opportunity to push the Volunteer Army out of Abkhazia and beyond. In the field of intelligence, Denikin's intelligence HQ attempted to cultivate ties with former Georgian army officers. However, the Social Democrats confronted them with the nationalism tinted with anti-imperialism.

The situation with the Bolsheviks proved more complex as they demonstrated a notable resilience and strength. The Bolsheviks were steeped in clandestine action during their illegal activities in the Empire. They were emboldened by the brutality that was not only tolerated but promoted by Lenin and implemented by Leon Trotsky as the head of the Red Army. The Bolsheviks undertook to destabilize and reabsorb all former imperial lands that gained independence—Georgia included. Notably, many of the cadres that the Bolsheviks deployed for subversion were Georgian communists. Veteran Philipe Makharadze, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and Stalin himself held both operational and policy positions and served as "handlers" of their networks.

The Bolshevik propaganda narrative asserted that Tbilisi was under the control of Western imperialist powers—first Germany, then the Entente powers—and that the revolutionary forces had the responsibility to confront this "puppet government."

The Bolshevik propaganda narrative asserted that Tbilisi was under the control of Western imperialist powers—first Germany, then the Entente powers—and that the revolutionary forces had the responsibility to confront this "puppet government." This message was disseminated through legal and clandestine newspapers to incite workers against Noe Jordania's Social-Democratic government. However, it had a significant presence among the urban working class and a strong electoral position. The Bolsheviks successfully initiated significant strikes in 1918 and, to a certain extent, in 1919, notably at the Poti port docks. However, the city's strategic decentralization and the strengthening of its trade unions played a crucial role in effectively managing labor discontent. The Bolsheviks' attempts to exacerbate existing divisions were more successful. Certain groups expressed discontent regarding the nationalization of land by the Social Democrats, particularly the aristocratic circles. Some adhered to an ethno-nationalist ideology, with Communists criticizing Tbilisi for what they saw as an absence of internationalism and "chauvinism." This criticism was based on Tbilisi's promotion of the use of the Georgian language in public administration, the reestablishment of the independence of the Georgian Church, and the promotion of Georgian nationalism. The ethnic card proved particularly damaging; even when revolts occurred for economic reasons, Bolshevik outlets presented them as ethnic, notably involving a pauperized population in Shida Kartli, which included many Ossetians but also Georgians, and which was suppressed rather brutally by the National Guard.

Paradoxically, the fact that the Social Democrats were the political cousins of the Bolsheviks during the Empire contributed to the development of Georgian resilience.

Paradoxically, the fact that the Social Democrats were the political cousins of the Bolsheviks during the Empire contributed to the development of Georgian resilience. Leaders in Tbilisi were well-versed in their former comrades' conspiratorial tendencies, and they themselves exhibited similar behaviors. In fact, some of their clandestine networks appear to have overlapped. At times, this was used to Georgia's advantage. For instance, when Denikin's chief of HQ, Nikolai Baratov, visited Tbilisi in September 1919, he was severely wounded in a bomb attack on his vehicle. Soviet historiography has attributed this attack to a Bolshevik cell, and a street in Tbilisi has long carried the name of the fallen attacker, Elbakidze, a name that is still commonly used today. However, recent findings by Georgian historians suggest that National Guard officers may have had contact with the attackers and may have either encouraged or failed to prevent the attack. Baratoff was on a diplomatic mission, but Tbilisi was aware of the efforts of the Volunteer Army to gain a foothold in Batumi, which the occupying British Army was about to leave. One strategy that was employed to gain a tactical advantage was to cripple Baratoff.

Russia Can Be Beaten

The experience of the Georgian Democratic Republic's intelligence services and political leadership demonstrates that Russia can be defeated even by Georgia when it comes to clandestine operations.

A brief review of Russia's imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet strategies toward Georgia reveals striking parallels. It is imperative to note that the experience of the Georgian Democratic Republic's intelligence services and political leadership demonstrates that Russia can be defeated even by Georgia when it comes to clandestine operations.

The first element is national and ideological coherence. The establishment of institutions that facilitate constructive dialogue is a crucial step in ensuring civic peace and thwarting subversive activities. The Bolsheviks, whose credo was to mobilize workers and the proletariat, were unsuccessful in their task. This was due to the fact that the Social Democrats often offered a working social model for these classes that did not include the same level of Communist brutality.

The second element is nationalist mobilization. When dealing with an imperial opponent, it is essential for the nation to unite under its leadership. This approach fosters a sense of motivation to persevere. Tbilisi responded to the "internationalist" rhetoric emanating from the Kremlin by emphasizing Georgian identity, sovereignty, and the cultural and civilizational choice of Europe. This approach was contrasted with the perceived "Oriental barbarism" and despotism embodied by the Bolsheviks. It appears that sidelining more nationalist elements for ideological reasons may have been an error. This decision may have led to their willing or unwilling collaboration. After the occupation, the Bolsheviks for a short time tolerated the right-wing National Democratic Party and even enrolled former army officers. However, they did not tolerate the Social Democrats or the National Guard, which led the resistance.

Thirdly, familiarity with adversaries cuts both ways: from 1918 to 1921, Georgian intelligence built a formidable network in Russia's North Caucasus, based on army officers as well as socialist underground members. The Georgian leadership and militia had intimate knowledge of the Bolshevik clandestine tactics, which helped them disarm their cells.

As Georgia becomes increasingly permeable and vulnerable to the Russian worldview, it is essential to keep these lessons in mind.

The illustration is inspired by the artwork of Polish artist Pawel Kuczynski.