Corridors of Power: How Connectivity Becomes the New Battleground in the South Caucasus

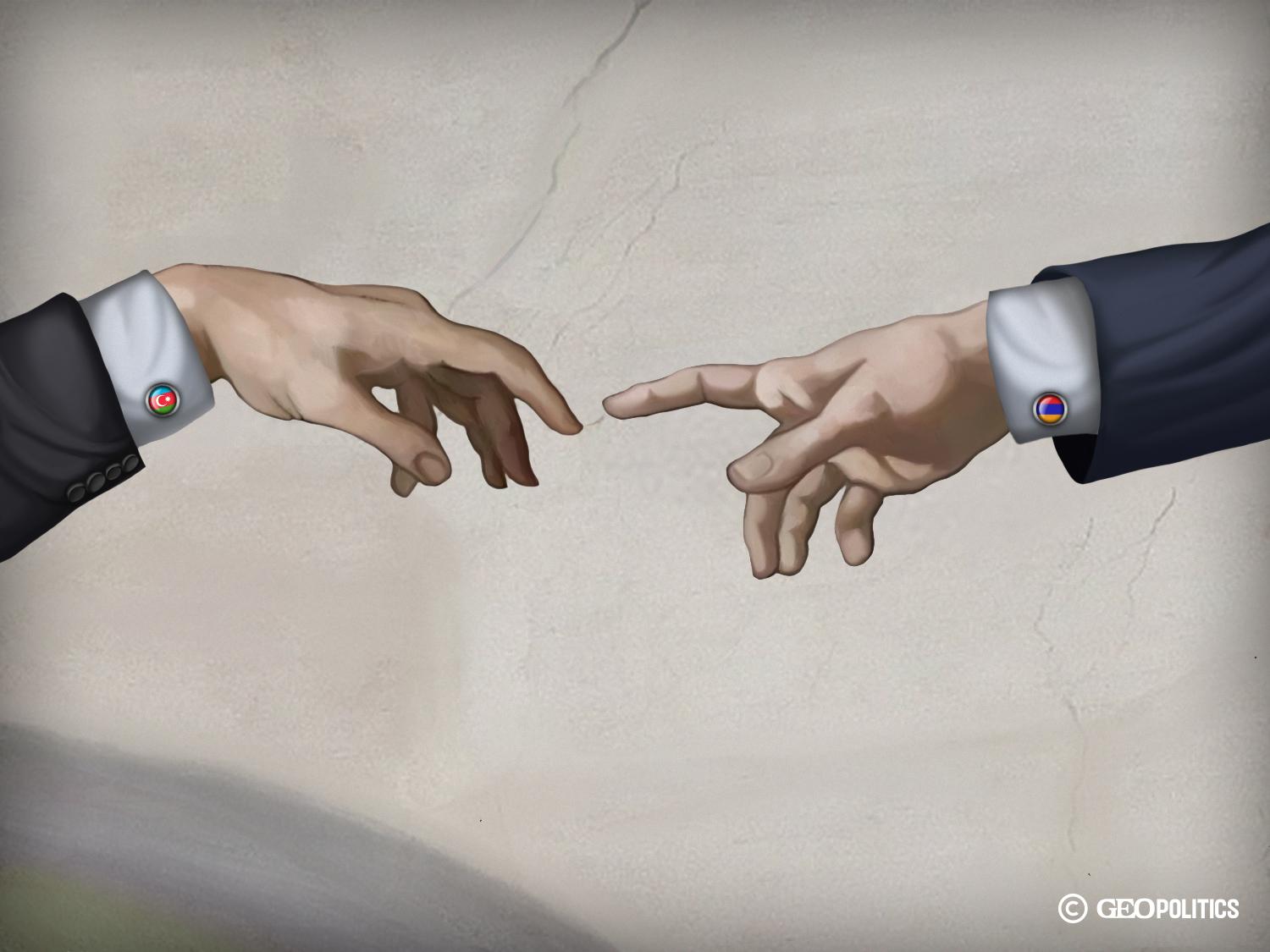

The post-2020 period was hailed as a turning point for the South Caucasus — a moment when Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia could shape their regional agenda without the overbearing weight of Russia’s influence. Moscow’s preoccupation with Ukraine, Armenia’s pivot away from its traditional alliances, and Azerbaijan’s ascendancy following its military victories seemed to enable a rare experiment in self-directed diplomacy.

Moreover, the EU’s 2023 decision to grant Georgia candidate status, along with intensified discussions on shared economic interests — including Black Sea connectivity, the revived Anaklia port project, the prospective undersea electricity cable, and proposals for enhanced digital links through a new submarine internet cable (complementing the existing one) or even space-based communication — have, on paper, created promising opportunities for new forms of regional integration. Notably, all of this has emerged without Moscow’s dominance.

Russia’s influence has not vanished; it has metastasized. In Georgia, the government’s authoritarian drift has followed a distinctly Russian script, reinforced by the passage of repressive laws, election manipulation, and a crackdown on the opposition, civil society, and free media.

However, by 2025, this illusion of autonomy is already unraveling. Russia’s influence has not vanished; it has metastasized. In Georgia, the government’s authoritarian drift has followed a distinctly Russian script, reinforced by the passage of repressive laws, election manipulation, and a crackdown on the opposition, civil society, and free media. In Armenia, the internal backlash to peace negotiations, led by pro-Russian actors, has destabilized Nikol Pashinyan’s position. Russia’s peacekeepers may have left Nagorno-Karabakh, but their shadow still lingers.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan and Türkiye have emerged as the dominant axis of regional power. Baku’s military triumphs and Türkiye’s strategic assertiveness have created a duo that actively reshapes regional dynamics, not through multilateralism but through strategic imposition. The bilateralization of Armenia-Azerbaijan talks, Azerbaijan’s rejection of international mediation, and the sidelining of the EU and the U.S. reflect this shift. The Trump administration’s lack of interest in the region and its economic potential adds to the vacuum, reinforcing the perception that Western actors are either absent or irrelevant in shaping the future of the South Caucasus. In this environment, Azerbaijan and Türkiye are not just filling a gap; they are redrawing the map to serve their strategic vision.

What initially appeared as a window for regional agency has morphed into a landscape of growing asymmetry where power, not consensus, sets the rules. In this new reality, connectivity is no longer a pathway to peace and prosperity but a strategic instrument of leverage and control.

Connectivity as a Tool of Leverage

The new era of South Caucasian diplomacy is defined by infrastructure, but not as a bridge of peace. Corridors are now symbols of sovereignty, tools of coercion, and prizes in the contest for regional dominance.

The new era of South Caucasian diplomacy is defined by infrastructure, but not as a bridge of peace. Corridors are now symbols of sovereignty, tools of coercion, and prizes in the contest for regional dominance.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of the so-called Zangezur (or Syunik) Corridor proposed by Azerbaijan as a land link to Nakhchivan, potentially opening the north-south and east-west trade routes through Azerbaijan. Baku’s maximalist push — demanding extraterritorial access policed by the Russian FSB through the Zangezur corridor — transformed a technical project into a strategic threat to Armenian sovereignty. President Aliyev’s rhetoric that “the Zangezur Corridor will definitely be opened, whether Armenia wants it or not” left little doubt. This puts Armenia in a conundrum – agree by coercion or resist and risk another territorial conflict. Neither seems a viable option at this stage.

Armenia’s counterproposal, the “Crossroads of Peace,” envisions mutual access, reciprocal sovereignty, and multilateral guarantees. But in a power-asymmetrical environment, such ideas remain aspirational. Baku sees the corridor not just as a logistical route but as a final piece of the post-war puzzle — a physical and symbolic reunification with Nakhchivan, bolstering Aliyev’s domestic and regional stature.

Even Georgia, once the default hub of east-west trade, is at risk of marginalization. A parallel branch of the Middle Corridor through Armenia could divert freight and investment, especially if geopolitical instability or Western distrust persists. With Anaklia’s future uncertain and Russian naval buildup in Ochamchire threatening Black Sea access, Georgia’s transit potential is under siege by both domestic choices and external constraints.

The Anaklia deep-sea port, as detailed elsewhere in this issue, remains far from completion. The Georgian government’s decision to award the project to a sanctioned Chinese company has yet to be implemented. Nearly a decade has been lost — first to the ruling party’s deliberate sabotage of the project for geopolitical and political reasons and later to its half-hearted revival efforts aimed at avoiding friction with Russia, the U.S., or China — an impossible balancing act. Today, it appears that the Georgian Dream, more focused on preserving and legitimizing its rule than on strategic development, treats Anaklia less as a national priority and more as a bargaining chip to gain favor with external actors willing to support the regime.

Meanwhile, Iran and Russia are anchoring the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) as their geo-economic lifeline. For Tehran, the corridor is a strategic hedge against sanctions and isolation. For Moscow, it is a sanctions-proof artery to Asia — one that bypasses the West and consolidates influence through logistics.

Connectivity, once promoted as a shared opportunity, now resembles a zero-sum game. If the post-2020 dream was connectivity as cooperation, the reality has become connectivity as coercion.

Corridors of Contestation

What unites the strategies of various regional actors is not cooperation but competition. And what is at stake is not only trade routes and connectivity-related proposals but regional order.

Ambitions are crisscrossing the South Caucasus: Azerbaijan’s Middle Corridor, Iran’s INSTC, Armenia’s multilateral vision, Russia’s push for oversight and control, Türkiye’s pan-Turkic goals, and Georgia’s balancing act tilting towards Moscow and mainly preoccupied with the regime’s survival. With the EU and the U.S. all but absent from the geopolitical discussions, the connectivity, defined by each actor on its terms, becomes a harder-to-reach goal. What unites the strategies of various regional actors is not cooperation but competition. And what is at stake is not only trade routes and connectivity-related proposals but regional order.

Azerbaijan and Türkiye are building an axis that ties transport to territorial influence. Baku’s integration into energy and freight networks — from the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline — underpins its leadership in the Organization of Turkic States. The Zangezur Corridor would seal this hegemony.

Armenia, meanwhile, faces contradictory imperatives. It seeks normalization with Azerbaijan and Türkiye to break out of isolation, yet fears that ceding control over corridors could compromise sovereignty. Its push to get rid of Russian presence and reengage with the EU through more common initiatives, such as visa liberalization or an updated Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement, signals a strategic shift, but economic dependence on Russia and energy reliance limit its room for maneuver.

Having lost formal security footholds in Armenia — symbolized by the withdrawal of peacekeepers from Nagorno-Karabakh, the expulsion of Russian border guards from Zvartnots Airport, and Yerevan’s de facto departure from the CSTO — Russia is now seeking indirect means to retain strategic leverage in the South Caucasus. Chief among them is corridor control.

Moscow’s interest in overseeing the Zangezur Corridor — the proposed transit route linking Azerbaijan proper to Nakhchivan through Armenia’s Syunik province — is not only about ensuring safe passage for freight. It is about reasserting itself as an indispensable regional player.

Moscow’s interest in overseeing the Zangezur Corridor — the proposed transit route linking Azerbaijan proper to Nakhchivan through Armenia’s Syunik province — is not only about ensuring safe passage for freight. It is about reasserting itself as an indispensable regional player. Article 9 of the 2020 ceasefire agreement, which vaguely refers to the unblocking of all economic and transport links and “unimpeded movement,” has been used by both Baku and Moscow to push for Russian Federal Security Service oversight of the corridor. This would allow Russia to insert itself into east-west connectivity projects that are increasingly bypassing its territory, especially the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), also known as the Middle Corridor.

In geopolitical terms, the corridor presents Russia with a twofold opportunity: first, to act as a gatekeeper in the trade infrastructure of the South Caucasus without requiring direct territorial control; second, to secure routes that facilitate sanctions evasion, particularly in sectors such as energy, dual-use goods, and strategic materials. The Baku-Dagestan-Russia corridor, especially via the Yarag-Kazmalyar crossing, already provides a logistical alternative to the increasingly scrutinized Verkhny Lars route.

Furthermore, by insisting on security oversight, rather than economic partnership, Russia can retain relevance even during the economic decline. This explains its rejection of alternative oversight proposals, such as Swiss or international monitoring forces for Zangezur. Control, not commerce, is the goal.

Russia’s corridor obsession reflects a deeper strategic adaptation: from peacekeeper to chokepoint manager, ensuring continued influence by physically embedding itself in the region’s arteries of trade.

In sum, Russia’s corridor obsession reflects a deeper strategic adaptation: from peacekeeper to chokepoint manager, ensuring continued influence by physically embedding itself in the region’s arteries of trade.

Iran’s position on connectivity in the South Caucasus is driven not by economic calculus alone but by existential strategic concerns. With regional adversaries encroaching, particularly Türkiye and Israel-backed Azerbaijan, Tehran views land corridors through Armenia as geopolitical lifelines, essential to preventing encirclement and preserving access to critical trade routes.

Iran opposes the Zangezur Corridor proposal vehemently, viewing it as an attempt by Baku and Ankara to create a contiguous Turkic belt from Central Asia to the Mediterranean, cutting Iran off from the South Caucasus and reducing its leverage. Tehran’s military leadership has repeatedly warned that any alteration of Armenia’s borders is a red line. The 2023 uptick in joint Iranian-Armenian military contacts and Foreign Minister Amir-Abdollahian’s remarks reaffirming Armenia’s territorial integrity were signals of Iran’s deep unease.

At the same time, Iran is doubling down on the International North-South Transport Corridor, which runs from India through Iranian ports like Bandar Abbas and Chabahar, up through Azerbaijan or Armenia, and into Russia. The INSTC is not only Iran’s most promising trade corridor but also its most sanctions-resilient route, particularly after the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and Tehran’s growing isolation from Western markets.

Iran’s urgency increased following the Houthi disruptions in the Red Sea beginning in late 2023. Attacks on shipping by Iran-aligned militias made it clear that Tehran sees land corridors as alternatives to maritime chokepoints vulnerable to interdiction or conflict. Tehran’s own officials have promoted the INSTC as a “safer alternative” to the Suez Canal and Russia has eagerly supported this framing.

Furthermore, Iran’s economic cooperation with Russia has intensified in this context. The completion of the Rasht–Astara railway, a vital missing link, is now prioritized. Infrastructure coordination, financing through Iranian banks, and integration with Caspian Sea ports like Anzali reflect the regime’s all-in investment in the INSTC vision.

For Tehran, therefore, the corridors through Armenia are not just trade routes. They are survival routes — essential for breaking out of diplomatic isolation, projecting regional relevance, and ensuring that Iran is not boxed in by a Turkic-NATO-Israeli arc to its north and west. If Trump-instigated negotiations on nuclear disarmament, especially with the participation of Russia, as Trump hinted in his tweet, succeed, Tehran’s goal of boosting its role in regional connectivity could become a reality.

Georgia: From Strategic Hub to Connectivity Dead End?

Georgia, once the uncontested east-west transit hub of the South Caucasus, is at real risk of losing its centrality in the region’s connectivity agenda. While it remains geographically pivotal — home to the Black Sea ports of Poti and Batumi, and a core component of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad, and the Middle Corridor — its political trajectory is casting serious doubt on its reliability as a partner for the West.

The revival of the Anaklia deep-sea port, long seen as Georgia’s strategic gateway to Europe and Asia, remains mired in political stagnation. Despite renewed interest, the project has not progressed and the decision to award it to a sanctioned Chinese company has further complicated matters. The ruling Georgian Dream party torpedoed the original Anaklia Consortium, backed by Western investors, for political reasons, fearing that strategic infrastructure under Western control would provoke Russian ire. The jealousy towards the possible builders of the port, now opposition politicians from the Lelo party, could have also played a role.

Now, Georgia finds itself struggling to attract Western attention and investment, not for lack of opportunity but due to growing mistrust. The adoption of Russian-type anti-democratic laws since 2024, mass repression of protesters, and democratic backsliding have alarmed the EU and the U.S. alike. Washington has suspended the strategic partnership, the European Union has cut the financial aid and stopped high-level contacts, which inevitably affects the decisions of European and American companies to invest in a country drifting closer to Russia and China.

Meanwhile, Georgia’s transit potential is also threatened by alternative routes. Should Armenia be integrated into east-west connectivity via Zangezur, and the Black Sea-Caspian traffic be rebalanced towards Azerbaijan-Dagestan, Georgia may face significant losses in freight traffic and customs revenues. The Zemo Lars crossing — vital for trade with Russia — could be eclipsed by Yarag-Kazmalyar if Moscow and Baku intensify cooperation.

Compounding the problem is the militarization of the Black Sea. Russia’s expansion of its naval presence in Ochamchire, in Georgia’s occupied Abkhazia, just 30 km from the proposed Anaklia port, is a strategic warning shot. It demonstrates that any attempt to turn Georgia into a Western trade hub will meet military pushback, further chilling investor enthusiasm.

In short, Georgia’s fate in the connectivity game now hinges not on geography but on governance. Without clarity of foreign policy, firm democratic credentials, and strategic alignment with the West, it risks becoming a country with a prime location but no invitations — bypassed by partners and boxed in by neighbors.

Among the many corridors that could reshape the South Caucasus, one remains conspicuously closed — the railway and highway link connecting Russia to Georgia and onward to Armenia through Abkhazia. Once a key artery of Soviet-era logistics, the Sochi-Sokhumi-Zugdidi railway, which traverses the strategic Enguri River, has been dormant since the war in Abkhazia in 1992-1993. Its reopening, under different geopolitical circumstances, could have been transformative.

In a context where Georgia remained committed to its European integration path and aligned with EU sanctions policy against Russia, such a project — implemented with international oversight and under status-neutral arrangements — might have had merit. It could have served as a confidence-building measure, re-establishing cross-Enguri trade, reducing isolation in Abkhazia, and reconnecting the broader South Caucasus with northern markets. The Enguri River, currently a de facto border and chokepoint, could have been reframed as a gateway for regulated commerce.

The opportunity was not merely theoretical. In 2011, Georgia and Russia reached a landmark agreement brokered by Switzerland, clearing the way for Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). As part of the deal, the parties agreed to establish an international monitoring mechanism for the movement of goods through the Abkhazia and South Ossetia corridors, involving a neutral private company — later identified as SGS (Société Générale de Surveillance) — to oversee the trade.

The agreement, while status-neutral and diplomatically significant, was never implemented by Georgia (or Russia). The GD government avoided selecting the monitoring company, failed to build the necessary infrastructure, and allowed the agreement’s political momentum to dissipate. This inertia was driven by fears of legitimizing Russian control over the occupied territories, internal political sensitivities, and a lack of vision. In hindsight, it was a missed strategic opening.

If implemented at the time, this arrangement could have served two purposes. It could have reinforced Georgia’s image as a constructive regional actor capable of pragmatic engagement without compromising sovereignty. And it would have enabled Georgia to retain leverage over trade routes passing through its internationally recognized territory with clear monitoring and international backing.

Taken together with the Anaklia deep-sea port, Georgia could have become the anchor of a dual-transit strategy — east-west via the Middle Corridor and north-south via a status-neutral corridor through Abkhazia. But both cards were squandered. Georgian Dram sabotaged Anaklia and the WTO trade agreement was shelved.

Today, the idea of reopening the Russia-Georgia-Armenia rail link via Abkhazia is politically toxic. With Georgia’s government under fire for democratic backsliding and passing the Kremlin-inspired restrictive laws, any attempt to revive the Abkhazia corridor would be seen as a capitulation to Moscow, both domestically and internationally.

Domestically, the public perception of the Georgian Dream as a pro-Russian force would be further entrenched. Activists and opposition figures would likely frame such a move as treasonous — a betrayal of Georgia’s territorial integrity and Western orientation.

Internationally, neither the EU, the United States, nor Azerbaijan, which historically views Armenia’s links to Russia with suspicion, would support a project that helps Russia bypass sanctions or strengthens Moscow’s foothold in the region.

What might have been a strategic trump card a decade ago is now a non-starter, buried under the weight of Georgia’s political drift, regional mistrust, and the changing nature of Russia’s role in the South Caucasus.

In effect, Georgia’s inaction has neutralized its leverage. By neither advancing the Anaklia project nor activating the WTO-brokered corridor through Abkhazia, it has ceded the initiative to others. Connectivity decisions that could have been made on Georgia’s terms, backed by the West and tied to European integration, are now viewed through a very different lens — as potential tools for Russian circumvention, not Georgian leadership.

Integration or Fragmentation?

The recent Armenia-Azerbaijan normalization process has opened a rare window for regional peacebuilding, and connectivity could be its most durable anchor. But for that to happen, corridors must be built not as tools of dominance but as frameworks of mutual benefit. So far, that vision remains elusive. The Zangezur Corridor continues to be framed by Azerbaijan in extraterritorial terms while Russia and Iran have co-opted the north-south axis for sanctions evasion and strategic maneuvering. Even the Middle Corridor, once hailed as a unifying route from China to Europe, risks fragmentation into competing branches based on geopolitical loyalties rather than logistical efficiency.

Tbilisi has squandered two potential game-changers: the Anaklia deep-sea port, which could have anchored Georgia as a Black Sea hub, and the WTO-brokered trade corridor through the occupied regions, which could have restored leverage over Russia while promoting status-neutral engagement.

The problem is not a lack of opportunity but a failure of political will, particularly in Georgia, but also in almost all regional powers. Tbilisi has squandered two potential game-changers: the Anaklia deep-sea port, which could have anchored Georgia as a Black Sea hub, and the WTO-brokered trade corridor through the occupied regions, which could have restored leverage over Russia while promoting status-neutral engagement. Both remain dormant. Instead of utilizing connectivity to reinforce sovereignty and regional agency, Georgia’s ruling party has opted for a path of appeasement, aligning itself with Russian interests at the expense of public trust, strategic autonomy, and Western support. What could have been built as a shield against authoritarian influence is now seen as a potential conduit for it.

The result is a new era of connectivity traps — corridors that promise integration but deliver dependence, routes that bind rather than bridge. For the wider region, this means more fragmentation, more suspicion, and fewer platforms for inclusive cooperation. For Georgia, it means the gradual erosion of its transit centrality and geopolitical credibility. Unless the region redefines connectivity not as a race for control but as a vehicle for coexistence, it risks turning infrastructure into the next frontier of rivalry — and losing peace just as it comes into view.