Peace, Power, and Paradoxes: Trump's Iran Gamble and Its Regional Reverberations

The greatness of a President is measured by the wars he has avoided - Donald Trump once declared. As his attempts to impose peace in Ukraine stall and dreams of “peace in 24 hours” or “in a few weeks” evaporate, the Iranian nuclear issue may well offer the American president another opportunity to claim greatness and, incidentally, peace in the eyes of the American voters. The latter are far more important to him than the opinion of any of the U.S. allies, even the oldest and most loyal.

The Trump administration is now attempting to revive the idea of a nuclear deal with Iran, something the West painstakingly and laboriously achieved in 2015 in Vienna, an agreement known as the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), which Trump walked away from in 2018, calling it a catastrophe. Trump was not the only one to look askance at the JCPOA. Israel made no secret of its dissatisfaction at the time (just as it is doing now about this new wave of negotiations), Gulf states were not happy, and even French diplomacy signed it reluctantly under pressure from the Obama administration. The key point was the lack of confidence in the Iranian leadership and the fear that the agreements and the consequent easing of sanctions would allow the Tehran “mollarchy” to prolong its life.

For this reason and because of the memory of General Qasem Soleimani's elimination by an American missile in January 2020 (he was known to be the true architect of Iran's regional influence and the right-hand man of the Supreme leader), Donald Trump's return to power for many was synonymous with an imminent increase in pressure on Teheran, even with the dramatic rise of the risk of war against Iran. The first steps of the Trump 2.0 administration did indeed point in this direction. In January, the White House reinstated the "maximum pressure" policy, aiming to reduce Iran's oil exports to zero. The administration imposed new sanctions targeting entities involved in Iran's oil trade, particularly those facilitating sales to China. The U.S. expanded its sanctions a few weeks later, targeting Iran's drone and ballistic missile programs and the entities in Iran and abroad involved in procuring components for these programs. Additionally, the U.S. sanctioned networks for facilitating the sale of Iranian liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in violation of U.S. sanctions.

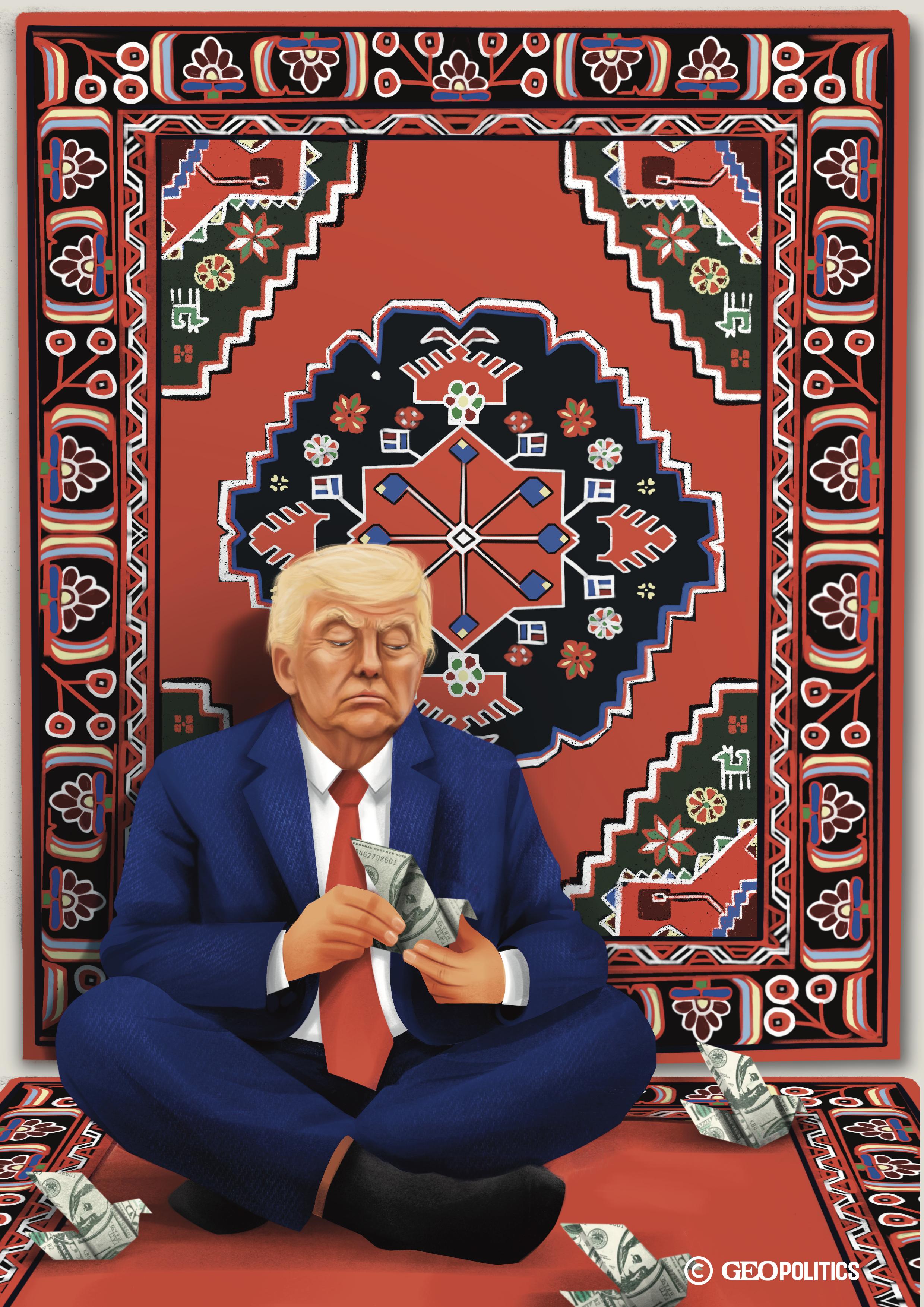

But on 7 March, President Trump made yet another breaking announcement that he had sent a letter to Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, proposing new nuclear negotiations. The letter reportedly demanded the full dismantling of Iran's nuclear program, the cessation of uranium enrichment, and an end to support for proxy groups like Hezbollah and the Houthis. Initially, Khamenei rejected the overture, accusing the U.S. of seeking dominance rather than genuine negotiation. However, by the end of March, Iran expressed readiness to engage in talks, leading to the initiation of negotiations in April. The peace doves Trump is sending to Tehran, however, are folded from dollar-bill origami—a not-so-subtle promise of sanctions relief and investment in exchange for submission. To this end, three rounds of negotiations have already taken place in Masqat, Oman, between Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and Donald Trump's special envoy for the Middle East, Steve Witkoff, and two rounds were organized in Rome.

The Logic Behind Iran’s Interest in Negotiations

Iran in 2025 is much more vulnerable than it was ten years ago when the nuclear deal was signed in Vienna.

Iran in 2025 is much more vulnerable than it was ten years ago when the nuclear deal was signed in Vienna. The regime is at bay, economically exhausted, internally contested, and now deprived of its regional proxies. Economic ties only with China and Russia did not help Iran to develop and grow, and the country needs to ease sanctions to attract Western investments.

Since the U.S. withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) in 2018, Tehran has significantly expanded its uranium enrichment activities. As of May 2025, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reports that Iran has accumulated approximately 408.6 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60% purity—a level just below weapons-grade. While Iran’s total stockpile of enriched uranium across all levels has reached around 9,247 kilograms, only a small portion of that is enriched to the highly sensitive 60% level. This accumulation remains a serious concern, as no other non-nuclear-weapon state is known to enrich uranium to this degree.

Since 2018, Iran has also accelerated the development of its ballistic missile program—a development that must be assessed in tandem with its advancing nuclear capabilities. In parallel, Tehran has reinforced its so-called “axis of resistance,” a network of militant and armed proxies including Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Palestine, the Houthis in Yemen, Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, and numerous Shia militias in Iraq. Through their military activities, these proxies have formed a strategic security buffer for the Iranian regime, allowing Tehran to project power across a broad arc stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean (Tehran-Baghdad-Damascus-Beirut) and the Red Sea via Sana’a.

And last but not least, the end of the JCPOA pushed Iran to reinforce strategic relations with Russia, which appeared in the coordinated action and alliance of the two countries in Syria and the massive delivery of Iranian military equipment, including Shahed drones, to Russia, after its all-out invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Paradoxically, despite Iran’s assertive and seemingly successful regional posture, the regime’s domestic stability has significantly eroded during this period. The country has been shaken by recurring waves of unrest, driven by mass protests, economic hardship, and mounting anti-regime sentiment. The Islamic Republic now faces a profound legitimacy challenge, rooted in widespread public discontent. This unrest stems not only from severe inflation and economic deterioration, exacerbated by international sanctions, but also from systemic repression, entrenched corruption among the ruling elites, and a pervasive sense of injustice across Iranian society.

Currently, Iran can barely export 600,000 barrels of oil daily, compared to more than two million barrels exported before 2018. The recent U.S. sanctions targeting Chinese companies importing Iranian oil, if the Chinese comply, will drastically reduce even these amounts. Inflation is devouring people's revenues, reaching an annual rate of around 40%. The anger of the population was all the greater as the regime, despite the hardships of its citizens, continued to spend billions on maintaining proxies throughout the Middle East.

Among the most significant anti-regime uprisings in recent years were the nationwide protests of November 2019, sparked by a sudden increase in gasoline prices. Spreading across more than a hundred cities, these demonstrations—later dubbed “Bloody Aban” (Aban being the Iranian calendar month)—were met with brutal repression, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of civilians at the hands of security forces. Even more prominent were the protests that erupted in September 2022 following the killing of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman, by Iran’s so-called “morality police.” Known by the rallying cry “Women, Life, Freedom,” these protests became the largest and most sustained popular movement since the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979, united by a singular, unequivocal demand: the end of the regime.

Some observers now argue that the Islamic Republic has shifted from a theocratic dictatorship to a military-security state.

As a consequence, the regime is grappling with a profound erosion of popular legitimacy, marked by what appears to be a deep—and possibly irreparable—rift between society and the state. This has led to an increasingly militarized approach to internal security, with growing reliance on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Basij militia. Some observers now argue that the Islamic Republic has shifted from a theocratic dictatorship to a military-security state. Its ongoing struggle to suppress dissent, despite sustained repression, signals a long-term breakdown in its authority and capacity to govern through consent.

Iran has also faced significant strategic setbacks. The so-called “Axis of Resistance” it painstakingly built, once appeared robust and assertive across multiple fronts. However, the Hamas terrorist attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s unprecedented military response drastically altered the regional balance of power. Israel has severely and enduringly weakened the military capabilities of both Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, leaving them in a state of near-collapse. In a domino effect, the Assad regime in Damascus succumbed to the offensive by Sunni militias of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), leading to the cutting of Hezbollah’s logistical support. Iran had long armed, funded, and sustained these proxies to create a protective buffer around its borders, but that buffer is now fractured. This erosion of regional leverage is prompting Tehran to adopt greater flexibility as it seeks to safeguard its own survival.

Faced with mounting internal and external pressures, Iran’s leadership—led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—opted to replace hardliner President Ebrahim Raisi, who conveniently perished in a helicopter crash, with the more moderate Masoud Pezeshkian in July 2024. The move appeared aimed at restoring a degree of public trust and signaling a less confrontational approach in foreign and regional policy. However, given the limited influence that previous so-called moderate presidents—Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005) and Hassan Rouhani (2013–2021)—had on the core policies of the Islamic Republic, neither the Iranian public nor Western governments harbor serious expectations about Pezeshkian’s ability to bring meaningful change. His appointment and subsequent election, marked by very low voter turnout, are widely seen as a tactical maneuver by the regime to project a façade of flexibility and stave off further instability.

The Revived Interest of the Regional Powers

Beyond the United States’ determination to secure a deal and Iran’s limited capacity to resist one, a notable shift has occurred among many of the Islamic Republic’s traditional rivals—most now favor a diplomatic approach toward Tehran, with the exception of Israel. The Gulf monarchies, especially Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), once firmly aligned with U.S. efforts to contain Iran’s nuclear ambitions, have reassessed their stance. In 2018, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi backed President Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA, citing Tehran’s ballistic missile development and destabilizing actions across the region. Yet by spring 2023, this posture had significantly softened. In a landmark agreement brokered by China, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to restore diplomatic ties, marking a major step toward regional de-escalation. By 2025, Saudi Arabia has gone a step further, offering to mediate between Washington and Tehran to help revive a nuclear accord. During a historic visit to Tehran, Saudi Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman encouraged Iran to consider President Trump’s proposal as a means to prevent a potential confrontation with Israel.

The Saudis and other Gulf states are strongly opposed to another war in the region. They recognize that any military strike on Iran—whether by Israel, the United States, or both—could escalate into a prolonged and destabilizing conflict, drawing in multiple countries and non-state actors. With ambitious development agendas underway, including Saudi Arabia’s plans to host the 2034 FIFA World Cup, regional stability is seen as essential. Another key factor is their privileged relationship with Washington: following Donald Trump’s high-profile Middle East tour and the signing of massive arms and investment deals worth hundreds of billions of dollars, Saudi and Emirati leaders have become the most favored regional actors in the White House—receiving far more attention and deference than traditional European allies or even Israel.

Still, even if a new nuclear agreement is reached, a full normalization of relations with Iran remains unlikely. While Iran’s nuclear ambitions are the most urgent concern, they are far from the only one. Tehran’s aggressive regional policies, hostility toward Israel, and ongoing missile development present persistent challenges. Most fundamentally, the Islamic Republic’s ideology is built on enmity toward the United States and Israel. The regime relies on its confrontation with the “Great Satan” and the “Zionist entity” as a cornerstone of its legitimacy. A reopened U.S. embassy in Tehran, with massive crowds of Iranians lining up for visas, would represent not just a political embarrassment but a devastating blow to the regime’s core narrative.

An Unexpected Gift for Moscow?

Expert discussions on Iran rarely highlight the fact that this country borders the South Caucasus. Even if it does not play a leading role there, developments in and around Iran can have significant consequences for the region. Today, however, the most influential factor shaping the geopolitics of the entire post-Soviet space—and indeed of the European continent as a whole—is the war in Ukraine, in which Iran also plays a notable role. This role consists of supporting Vladimir Putin’s war machine through the supply of weapons manufactured in Iran and the joint production of military equipment. Iran and Russia also rely on covert mechanisms, such as gold transfers and the use of intermediary countries, to bypass international sanctions.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Tehran and Moscow have considerably deepened their military cooperation, engaging in joint arms production and technology transfers.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Tehran and Moscow have considerably deepened their military cooperation, engaging in joint arms production and technology transfers. For instance, Russia has set up a drone factory in the Elabuga Special Economic Zone in Tatarstan, where it produces Iranian-designed Shahed drones, rebranded as Geran-2. Iran has reportedly also delivered ballistic missiles, such as the Fath-360, which have been used against Ukraine. In May 2025, the Iranian parliament ratified a 20-year strategic partnership agreement with Russia, formalizing their defense ties.

Russia and Iran’s deepening military ties are a serious concern for Europe, which backs Ukraine’s independence and views Moscow as the principal threat to the continent’s security.

What impact could a potential U.S.-Iran deal have on the war in Ukraine? Most likely, the American negotiators avoided addressing the issue of Iran’s military cooperation with Russia. The talks with Tehran’s envoys in Muscat and Rome appear to have focused solely on nuclear matters. Unlike the JCPOA negotiations, the Europeans (France, the United Kingdom, and Germany) are no longer involved—neither the Americans nor the Iranians want them at the table. Yet Russia and Iran’s deepening military ties are a serious concern for Europe, which backs Ukraine’s independence and views Moscow as the principal threat to the continent’s security.

Thus, if Washington and Tehran reach an agreement on uranium enrichment levels, stockpile limits, the import of nuclear materials from third countries, and conditions for permanent inspections, U.S. sanctions—at least a significant portion of them—will be lifted. This would inject new life into the Iranian economy and strengthen a regime that will likely continue its military cooperation with Russia with even greater energy. In other words, we might see more Shaheds and Iranian missiles against Ukraine.

The nature of Europe’s relationship with Iran has changed drastically in recent years. During the JCPOA era, European governments largely supported normalization with Tehran, the lifting of sanctions, and even rushed to invest in the Iranian market. Today, however, Europe’s stance on the Islamic Republic is far tougher than Washington’s. Beyond the nuclear file, what makes normalization nearly impossible are the brutal crackdowns following the “Women, Life, Freedom” uprising and Iran’s appalling human rights record and democratic regression.

The Trump administration views the situation very differently. It shows little concern for Iran’s domestic repression or its military alliance with Russia. On the contrary, Trump hopes to leverage the close ties between Moscow and Tehran to reach a deal with Russia serving as the intermediary. Both Trump and his envoy Richard Goldberg openly acknowledge that Iran is a topic of discussion in their contacts with the Kremlin and they count on Putin’s assistance. There is little reason to believe the Russian leader would refuse—on the contrary, he is likely to help, and at Ukraine’s expense.

It is worth recalling that this idea of using Russia to broker a deal with Iran is not new. President Obama also made this strategic misstep during his term, although at that time, Russia, while already the aggressor in Georgia and the occupier of Crimea, had not yet launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

If, in a deal with Moscow, the West fails to demand an end to Russian-Iranian military cooperation while Russia, for example, insists on halting NATO enlargement, then that cooperation will only intensify. Sanctions relief would embolden both regimes.

What holds true for Trump’s approach to Iran also applies to his posture toward Russia: if, in a deal with Moscow, the West fails to demand an end to Russian-Iranian military cooperation while Russia, for example, insists on halting NATO enlargement, then that cooperation will only intensify. Sanctions relief would embolden both regimes. The fundamental error lies in Washington’s attempt to treat negotiations with these two adversarial regimes separately when, in reality, they are deeply aligned and mutually reinforcing.

New Opportunities for the Caucasus-Black Sea Region

Beyond its implications for the Russia-Ukraine war, a potential U.S.-Iran agreement could also have a direct impact on the three South Caucasus countries.

Azerbaijan is likely to be the most affected. Notably, it was the only country in the region visited by Steve Witkoff, the chief U.S. negotiator with Iran, in March, shortly after Trump’s letter to Ayatollah Khamenei became public. Azerbaijan maintains an ambivalent relationship with Tehran, historically marked by tensions over national identity, conflicting historical narratives, Iran’s stance during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–1994), and the status of the sizable Azerbaijani population in Iran. While these tensions have eased somewhat in recent years, they persist beneath the surface.

Despite these complex ties, Baku has no interest in a military conflict involving Iran. A war, especially one initiated by Israel or the United States, could destabilize Azerbaijan, potentially triggering a wave of (mostly ethnic Azerbaijani) refugees from Iran. Moreover, if Tehran sought to retaliate against Azerbaijan for its close partnership with Israel, the country’s vital oil infrastructure, within easy reach of Iranian missiles, would be an obvious target.

Yet, full normalization of Iran’s global status could also pose challenges for Baku. The reentry of Iranian oil and gas into world markets could depress energy prices, threatening Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon-dependent economy. In addition, a reintegrated Iran might seek a greater role in East-West trade corridors, potentially undermining Azerbaijan’s position as a key transit hub in the South Caucasus.

Strategically, the resurgence of Iran, even as a non-nuclear regional power, runs counter to the interests of Azerbaijan’s main allies. Türkiye sees Iran as a regional competitor while Israel regards it as an outright adversary. For Baku, then, peace with Iran is acceptable—but not at the cost of empowering Tehran politically, economically, or militarily.

Armenia, by contrast, has enjoyed consistently positive relations with Iran since gaining independence. Tehran supported Yerevan during the 1990s conflict with Azerbaijan, helping deliver Russian arms and natural gas to offset Armenia’s severe energy shortages. To this day, Armenia remains Iran’s largest trading partner in the South Caucasus.

More recently, however, Armenia has begun pivoting toward the West, particularly Europe, spurred by a sense of Russian abandonment after the loss of Karabakh. A U.S.-Iran agreement could open new economic opportunities for Armenia, including access to cheaper energy. A normalized Iran, better integrated into global markets, could serve as a partial substitute for an increasingly unreliable Russia. Armenia might also benefit from its geographic position as a potential land bridge between Iran and Georgia, facilitating trade to the Black Sea and beyond. Politically, however, alignment with the Tehran-Moscow axis no longer seems to be Yerevan’s priority.

Georgia, the only South Caucasus state without a direct border with Iran, would experience fewer immediate economic gains from sanctions relief. Nevertheless, Iranian goods could reach Georgia via Armenia or Azerbaijan, thereby boosting activity in its Black Sea ports, such as Batumi and Poti. Georgia could leverage its location to position itself as a transit hub for Iran-Europe trade, particularly through cooperation with the EU or Chinese infrastructure initiatives, such as the International North-South Transport Corridor.

Politically, the ruling Georgian Dream party—now increasingly alienated from the EU and the United States—has been seeking closer ties with Iran.

Politically, the ruling Georgian Dream party—now increasingly alienated from the EU and the United States—has been seeking closer ties with Iran. The attendance of Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze at President Raisi’s funeral, standing alongside Hezbollah figures, drew intense criticism from Washington and is now frequently cited as evidence of Georgia’s drift from the West.

Should Washington and Tehran reach an agreement, the Georgian government may further solidify its rapprochement with Iran, framing it as consistent with U.S. policy. However, Tbilisi will need to tread carefully to avoid antagonizing Baku, whose political and economic influence in Georgia is steadily growing. If Georgia’s overtures to Iran extend too far, it could jeopardize its increasingly important relationship with Azerbaijan.

The prospect of a renewed U.S.-Iran nuclear agreement vividly underscores the contradictions and trade-offs at the heart of Donald Trump’s foreign policy. Framed domestically as a victory for peace over conflict, such a deal would bolster Trump’s electoral narrative by highlighting his signature brand of bold, transactional diplomacy. However, the implications of such an agreement would stretch far beyond the borders of Iran and the United States.

Reintegrating Iran into global political and economic systems without securing serious commitments risks empowering the regime rather than moderating it. In the absence of concrete guarantees regarding its support for militant proxies, its ballistic missile program, and—most critically—its expanding military partnership with Russia, the agreement could ultimately reinforce two regimes, in Tehran and Moscow, that actively undermine the existing international order.

For Europe, particularly states bordering Russia and relying on transatlantic solidarity to counter Putin’s war in Ukraine, the prospect of ignoring or downplaying the Iran-Russia nexus is deeply concerning.

For Europe, particularly states bordering Russia and relying on transatlantic solidarity to counter Putin’s war in Ukraine, the prospect of ignoring or downplaying the Iran-Russia nexus is deeply concerning. Should Washington lift sanctions on Tehran without addressing this military alliance—and worse, rely on Moscow as a backchannel to finalize the deal—it will be seen not as a diplomatic breakthrough but as a grave strategic misjudgment across the European continent.