Readied to Serve: From Civil Service to Political Servants under Georgian Dream

On 20 February 2025, the rump Georgian Parliament, where only MPs from the Georgian Dream party sit, abolished the Civil Service Bureau, a body created in 2004 which aimed, according to its website, at “implementing a unified state policy in the field of civil service to align with European Union values and principles of public administration.” That symbolic decision marked a final breakoff of Georgia’s ruling party from those very principles - one of the “fundamentals” of the EU accession process.

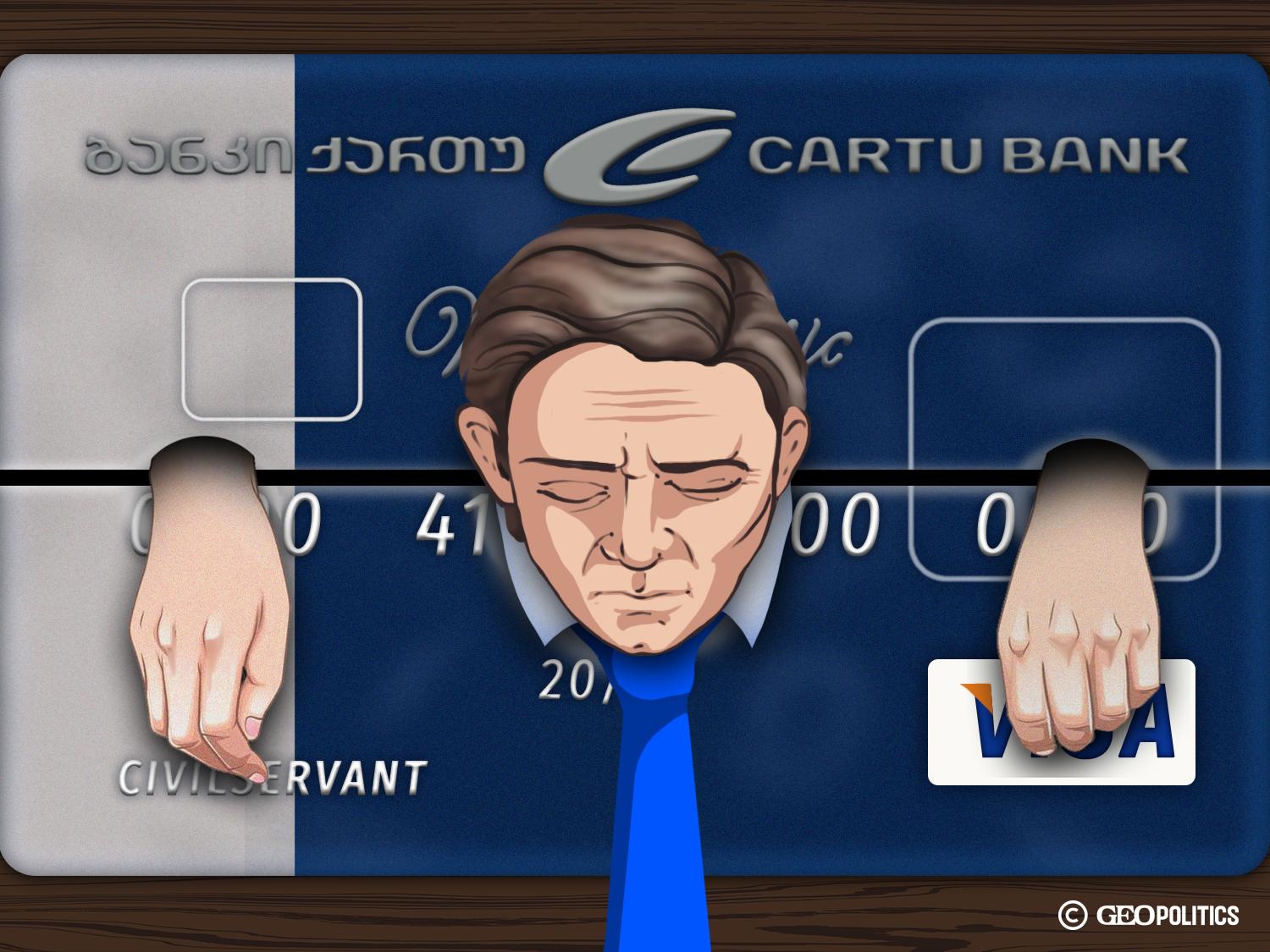

On the New Year’s Eve of 2025, over 50 civil servants received their dismissal letters. One of the first acts of Mikheil Kavelashvili, inaugurated president by a single-party electoral college on 29 December 2024, was to sign into law the changes that established political dominance over the civil service and abolished the political independence of senior civil servant positions and made it easier to fire or hire them on a political whim, immediately upon his inauguration.

Curiously, it was the Georgian Dream that initiated the new Law on Civil Service in 2015, putting the country’s administration on a path of approximation with EU standards. The law and the strategy that went with it were generously supported – financially and in kind, through training, partnerships, and counselling – by the European Union as well as by others such as the government of the United Kingdom (through UNDP), Germany (through GIZ) and the United States (through USAID). These programs and the dedication of the individual civil servants brought important results, even if often invisible to ordinary citizens. The government's policymaking process was streamlined and put on a solid methodological basis across the ministries. Human resources policies were also synchronized to ensure a professional, merit-based process. Steps were also made to unify the training for the new civil servants and integrate topics such as non-discrimination. Largely thanks to these civil servants, Georgia administratively responded to the exceptional opportunity of the EU candidacy in record time.

So what went wrong and what lessons must international actors retain from this abrupt collapse?

Reversal of the Tide?

States came to the idea of a professional civil service as the complexity of state management and international relations grew over time. By the 17th century, European courts realized officials who attained their positions through protection or bribes were no longer good enough. Few “fonctionnaires” were appointed. Experience was particularly valued in managing the crown’s finances and the military. However, the notion of a “civil servant” came about first in the East India Company, which started competitive recruitment in 1806.

The 1854 Northcote-Trevelyan Report generalized the practices of merit-based recruitment and career path, setting a division between “technical” and “administrative” posts. This foundational model was enriched in the 20th century. In the democracies of the 1960s and the 1970s, the notion prevailed that professional state servants utterly serve the legal order and public interest, even though they are subordinate to elected political leadership. By the 1980s, the New Public Management approach dictated that administration serves citizens and provides state services.

Both of these 20th-century developments fed into the European Principles of Public Administration that set the freedom from political patronage as its cornerstone and established the “policy process” as the key avenue through which elected leaders channel their publicly approved programs via the machinery of state. In this model, civil servants are topical experts and service providers. Their most senior representatives, almost on par with political leaders, ensure that the political decisions conform to the realm of Constitutional legality.

The Georgian Dream speaks of the Deep State as some kind of global conspiracy, but that term in the mouth of populist leaders with authoritarian tendencies refers, more often than not, to the civil service, independent institutions, and the so-called “established media.”

It is this very concept of professional, politically neutral administration that is coming under fire, not only in Georgia but also in some established democracies. The Georgian Dream speaks of the Deep State as some kind of global conspiracy, but that term in the mouth of populist leaders with authoritarian tendencies refers, more often than not, to the civil service, independent institutions, and the so-called “established media.” In the U.S., the calls to “defeat the administrative state” are close to the MAGA mainstream. In Europe, too, the populist leaderships rail against the so-called “unelected officials” of the European Commission based on the same premise – that their legitimacy acquired through professionally serving the legal order is inferior and thus should remain subordinate to that granted by (often assumed) popular mandate.

In this sense, the leadership in Tbilisi is riding the reversal of the international tide to push for its own partisan benefit. But from another point of view, strengthening the professional civil service goes inherently against the incentives of political leadership.

Hesitant Reforms

Empowering a politically independent, professional, career-based, and citizen-oriented civil service means democratic elected leaders sharing crucial bits of power and – importantly for a democratic process – credit for success. In a paternalistic state like Georgia, top executives are expected to – and credited with – small advances in people’s lives. A village water supply repaired, a pothole fixed, social assistance delivered to those in need – all of these small but crucial benefits can be claimed for political credit or be implemented by the civil service (or, for that matter, local government). The first way gives political brownie points to the leaders and benefits the few. The second way goes invisible but has the potential to help many. It is one thing in countries where the civil service seemingly “always” existed and quite another thing in places where the ruling party and the executive have always dominated the civil service. In these places, politicians need additional incentives to opt for sharing power and establishing a civil service.

This is precisely what happened in the early 2000s. Georgians had had enough of the government's ineptness, that brought the country to the verge of state failure. The new administration in 2003 set out to change that and made reformed public services (civil registry, property registry, etc.) into trademark successes. Young people and seasoned professionals were brought into the civil service and its prestige grew. But impressive as it was, the progress was uneven – the United National Movement administration never conceded to a fully professional, unified civil service. The ministries competed for qualified staff and those with higher budgets and prestige benefited disproportionately. This meant that while the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of the Interior became star reformers, important agencies such as the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare were held back. Crucially, the United National Movement never introduced the position of senior civil servants (also known as state secretaries in some European countries) who lead civil servants in any given ministry or agency and are (almost) co-equal interlocutors to a minister. The minister governs while the state secretary manages – in conversations with the author, representatives of the former administration in 2010 argued that this concept was too inflexible, alien to the organizational culture, and, ultimately, politically inexpedient.

When the Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, they were deeply suspicious of civil servants hired under the preceding regime. At the same time, however, the ruling party tried to mark its credentials as a pro-European force and willingly followed the European Union's advice to bolster the civil service. By 2015, the Georgian Dream was often mocked for the ineptness of its administration and the new Prime Minister, Irakli Garibashvili, bet on civil service reform to make his mark. In 2015, the new Law on Civil Service was born. Yet, its concept and implementation suffered from three key weaknesses.

Politicized Process

The politicization of the reform process frayed its foundations. The reform was supposed to build a firewall between the political leadership and the civil service. In practice, however, high-ranking officials and political decision-makers—often lacking genuine reform experience—consistently intervened in operational details such as performance evaluations, recruitment processes, and training programs. This not only diluted the reform’s transformative potential but also reinforced informal networks that were based on loyalty and patronage rather than merit. The political leaders never intended to “let go” of their primacy.

Regulatory Inadequacies

Another critical inherent weakness was the fragmented legal and regulatory framework. The initial legislative design was never implemented. The reform’s success hinged on the swift adoption of a unified set of laws and bylaws. However, persistent delays in legislating key components, such as the laws on remuneration and the status of Legal Entities of Public Law (LEPLs), created a protracted state of uncertainty. These delays allowed entrenched interests to maneuver around the intended reforms, thereby preserving practices that maintained and expanded the loopholes for partisan/political influence. LEPLs and local government (initially supposed to be kept out of the Law’s purview) became the key loopholes for consolidating political influence as reservoirs for building patronage networks.

Professionalization of the civil service never touched the senior civil service. In fact, the senior civil servant/state secretary positions were never created. LEPLs were never properly brought under the umbrella of civil service law with multiple reports that many of them were used as a reservoir for partisan mobilization, especially at a local level.

Insufficient Institutional Capacity and Leadership

The lack of a cohesive, professionally driven vision for civil service reform meant that even when technical guidance was available from international partners, it was not translated into practice or ignored when it clashed with partisan agendas.

Finally, the reform effort was undermined by chronic deficiencies in institutional capacity. The Civil Service Bureau was never integrated into the executive management structure and remained a quasi-agency without sufficient “pull power” beyond spearheading technical adjustments in implementing policy processes. Without strong, dedicated leadership to champion the reform agenda, the political imperative further diluted the intended impact. The lack of a cohesive, professionally driven vision for civil service reform meant that even when technical guidance was available from international partners, it was not translated into practice or ignored when it clashed with partisan agendas.

Downhill

Yet, even with some hesitant changes, the Georgian civil service was exhibiting performance appreciated by most citizens, especially in the areas where they came into direct contact with the administration. The inertia of reforms has kept qualified and motivated civil servants inside most center-of-government agencies. Yet, it has been a worry of many experts, including the author, that the adapted legislation and rules of procedure were primarily implemented formally. They co-existed with the patrimonial organizational culture dominated by the politically appointed minister who unified political and administrative roles. It has long been evident that such centralization created the expectations and culture of personal loyalty, while the absence of the position of senior civil servant meant individual officers were defenseless against the political diktat. While the Civil Service Bureau lacked the power to arbitrate personal disputes, going to the courts to defend one’s interests, as, for example, a whistleblower, was considered an extremely costly step.

Already in 2020, the concerns about informal security surveillance on civil service were brought into sharp contrast during the so-called "cartographers’ case” when, during the election campaign, two civil servants were charged with alleged treason. The Public Defender of Georgia identified political motives behind the allegations and while the two civil servants were released on bail in January 2021, the case was never closed.

By the time local elections were held in 2021, political leaders had exploited the civil service to further entrench party interests. The OSCE/ODIHR noted that the ruling party had “blurred the line between the party and the state, at odds with OSCE commitments and good practice.” Incidents such as the mobilization of public servants for partisan rallies, the overt politicization of local governance and the quasi-state agencies, and the public pronouncements by top officials underscored a deliberate blurring of the lines between state institutions and party politics. These measures, taken ostensibly to secure electoral victories by the ruling party, directly undermined the impartiality and professionalism required for effective public administration reform. Moreover, they created an atmosphere where these qualities were less and less valued by the political leadership.

Cases of using “reorganization” as a pretext for firing civil servants whose partisan loyalty was questioned accelerated from 2021 onwards.

A policy brief published by the Caucasus University in late 2021 found that 6,434 civil servants were terminated from the civil service in this period, which is a considerable number since the Civil Service Bureau reported a total of 14,826 civil servants in Georgia in 2021 (excluding the Ministry of the Interior). Repeated cases of arbitrary dismissal have been reported since and even though former civil servants often won their cases in court, they were rarely restored to their positions. Cases of using “reorganization” as a pretext for firing civil servants whose partisan loyalty was questioned accelerated from 2021 onwards.

From the end of 2022, the ruling party, first indirectly, through affiliated radical political movements, and then openly, moved to restrict the operation of independent civil society groups and accused Western partners of fomenting dissent. The debate over the passage of the restrictive “law on foreign agents” dominated the public debate in 2023 and 2024, leading to widespread protests, which were often violently suppressed.

The manipulation of public institutions for electoral gain, combined with selective enforcement of regulations, created a double standard in governance. This double standard eroded the legitimacy of reform efforts as civil servants became increasingly demotivated by an environment that rewards loyalty over competence.

Between 2021 and 2025, the political landscape in Georgia experienced a series of dramatic shifts that fundamentally undermined the premises of the public administration reform. The continuous cycle of disruptions led to the erosion of core principles of European public administration—transparency, accountability, efficiency, and a citizen-oriented approach. The manipulation of public institutions for electoral gain, combined with selective enforcement of regulations, created a double standard in governance. This double standard eroded the legitimacy of reform efforts as civil servants became increasingly demotivated by an environment that rewards loyalty over competence.

Serving Repression?

Many reforms since 2003, in continuity between the two, politically viciously opposed administrations, did contribute to building and sustaining the civil service's resilience as long as possible. Most civil servants trained and coached through these efforts – often with foreign support – have fulfilled their duties faithfully to their oath of serving the Constitution. Hundreds – including the officers of the Civil Service Bureau – have spoken out at a critical juncture when the government suspended the accession process in the EU, saying it was going against Constitutional provisions.

Yet, many civil servants continue to fulfill their functions, even as in 2024 and early 2025 when Georgia experienced both legislative changes and societal events that distanced it considerably from the policy objectives still enshrined in official strategic documents and the Constitution.

Legislative changes introduced since 2024 and challenged by constitutional lawyers have affected essential freedoms. They restricted LGBTQI+ rights, abolished mandatory gender quotas in parliamentary elections, proposed a legislative package that seeks to eliminate the terms "gender" and "gender identity" from all Georgian legislation, facilitated offshore capital transfers, and instated the controversial "foreign influence" laws, severely limiting the operations of civil society organizations and curbing media freedom. Changes to the administrative offenses code and the criminal code put many civic activists on the docket – or in prisons.

So, was public administration reform a complete failure? The answer is nuanced.

Despite apparent failures, they created a residual organizational and professional knowledge that may again become relevant if and when Georgia’s democratic trajectory is restored and is likely to contribute to citizens receiving an acceptable quality of service in areas that are least affected by the unfolding crisis. The development of local administrative expertise in areas such as policy planning, the assessment of government programs and costing, budget planning and public services strengthens the country’s long-term capacity for policy development and implementation should the environment change.

Without institutional safeguards to protect professional integrity and ensure continuity, the foreign expertise directed toward civil service and public administration reforms is easily wasted.

These failures must also serve as a lesson that, without institutional safeguards to protect professional integrity and ensure continuity, the foreign expertise directed toward civil service and public administration reforms is easily wasted. Any effort to support countries in their transition toward European standards must involve continuous assessment of the implementation context, including political messaging, as civil service reform is not merely a technical or administrative process. Above all, it requires leadership committed to changing the attitudes of the political elite and the ring-fencing of civil servants who are working to drive this transformation.