Turning the Irony of History into a Big Success for Georgia

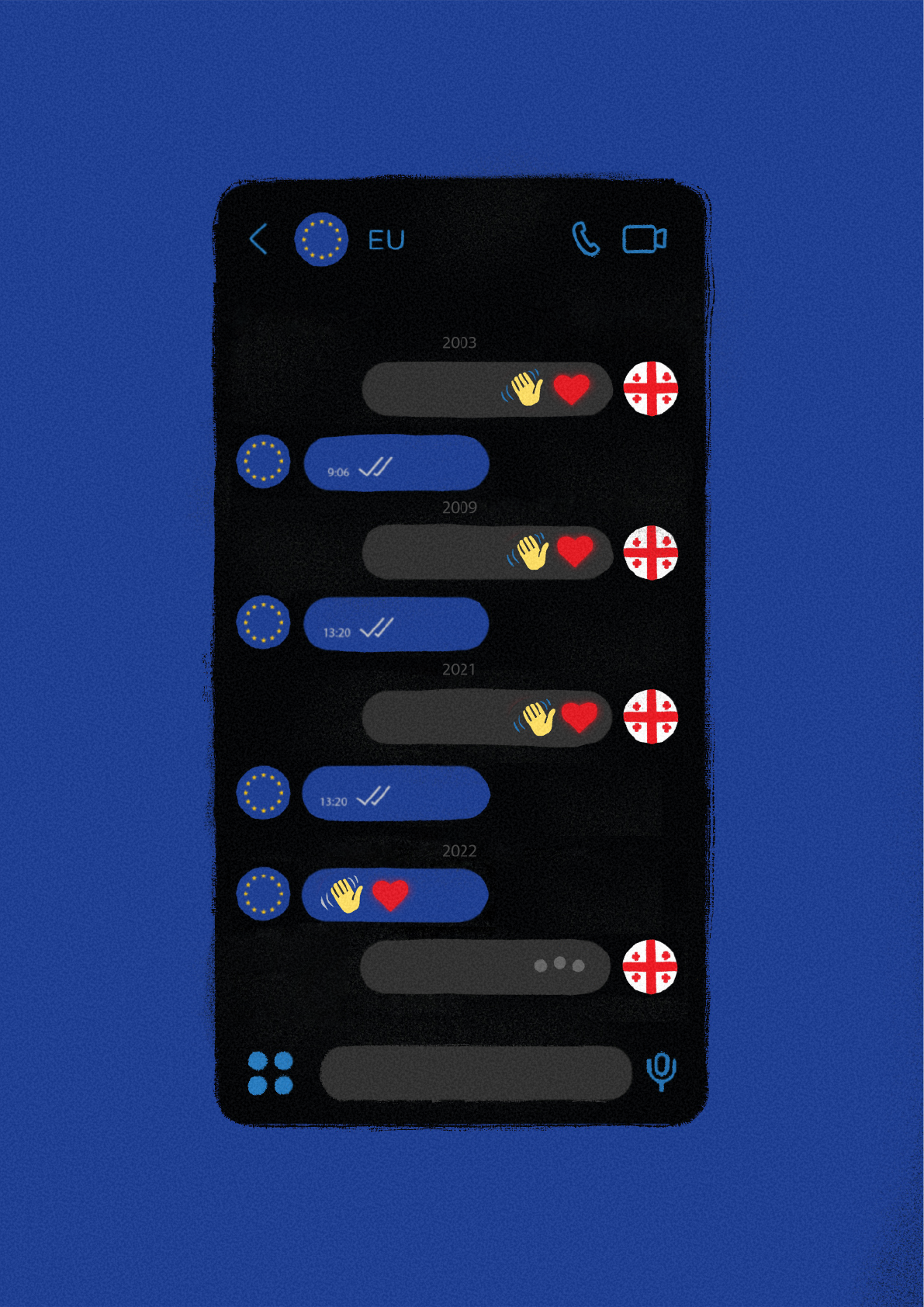

Charlie Chaplin once said that the irony of life was doing wrong things at the right moment or doing right things at the wrong moment. It is hard not to see the irony that the EU wants to speed up Georgia’s European integration now when the least pro-European Georgian Dream (GD) government since Georgia’s independence is in power. The previous highly pro-European United National Movement (UNM) government (2004-2012) never saw such enthusiasm regarding its aspiration to join the EU.

European Commission recommended offering candidate status “with conditions to be met” to the government that calls the EU “unfair,” “oppressive,” and accuses the Europeans of trying to drag Tbilisi into the war with Russia.

On November 8, 2023, the European Com- mission recommended offering candidate status “with conditions to be met” to the government that calls the EU “unfair,” “oppressive,” and accuses the Europeans of trying to drag Tbilisi into the war with Russia. Just 15 years ago, many European diplomats and politicians could not hide, at best, their amusement and, at worst, their annoyance at seeing European flags hoisted on all Georgian public buildings by the decision of the UNM government: “You are not an EU member, and you will not get there anytime soon” was the most common reaction at the time.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the topic of EU enlargement reemerged on the policy agenda in Brussels and among the member states. The opening of the member- ship path for the Eastern Trio (Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia) and beyond (several Western Balkan candidacies are simmering again, and some have started dreaming about bringing Armenia in shortly) is Ukraine-driven. It is both Russia's extreme revisionism and the Ukrainian armed forces’ heroic resistance that created the momentum that the EU cannot ignore. There is now a “strategic need” for enlargement, and no other choice exists. In this, the new wave of enlargement will differ from the previous ones, driven by the opportunity created by the collapse of communism and the positive agenda of uniting the European continent under freedom and democracy banners. In the current historical context, Brussels and other European capitals understand that the cost of non-enlargement is more significant than that of enlargement.

Georgia's good fortune is to be caught by Brussels on the right side of the new dividing lines. With Russia and the new camp of authoritarian states on one side and Ukraine and the West on the other, the EU perceives Georgia to be on the right side becauseof the strong Europhilia of Georgia's population, despite the markedly Eurosceptic, not to say Europhobic, tendencies of its government.

This decision, however, raises many questions. Is granting Georgia candidate status in these circumstances a good choice? Will it have positive medium- or long-term consequences for Georgia and the EU? What can be done to avoid making the same past mistakes? How can the negative scenarios that have characterized older candidate countries (e.g., Serbia and Turkey) be avoided? How should the increasing Russian influence be countered and the subsequent decline of popular support for EU membership be avoided? How can the enlargement process stop the slide toward authoritarianism with- out substantial reforms?

EU-Georgia Relations under UNM and GD: A Swinging “je t'aime, moi non plus”

For Georgia, the EU is almost unconditional love.

For Georgia, the EU is almost unconditional love. The desire for Europe, especially among the cultural and intellectual elites, predates the country's independence, even if the fascination with Europe is more recent for ordinary Georgians and probably follows other imperatives than sharing the same values. An analysis of the roots and causes of the Georgian population's Europhilia is not the purpose of this piece. Still, it is a decisive factor worth considering.

The EU’s response to this almost blind and unconditional love depended on which phase the Georgia-EU relations were in. Before the November 20023 Rose Revolution, Georgia and the entire Caucasus region were seen as, above all, a potential source of such problems as ethnic conflicts, crime, and refugees. The reforms of the Rose Revolution in Georgia sparked increased European interest in Georgia during the 2000s. However, Georgia was still considered just a neighbor with no immediate prospects of joining the “European club.” The Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008, marking Moscow's first military foray beyond its borders since Afghanistan, significantly altered European geopolitical perceptions, highlighting Russia as a rising threat to the continent. The war's impact on geopolitical dynamics led to the creation of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative, officially launched in 2009.

With the EaP, Georgia had the chance to negotiate the Association Agreement (AA) and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU. As is often the case in EU policies, an assumed ambiguity and operational misunderstandings emerged. While most Western and Southern European members thought the AA was a tool to avoid any eventuality of enlargement, the pro-enlargement “usual suspects” (Po- land, Baltics) along with the Eastern European states signatories to the AA (Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia), considered these treaties as a first step towards future enlargement, even if the prospects for this future enlargement seemed ambiguous and distant at the time.

Following Chaplin's definition of irony, the problem with the AA, the DCFTA, and the visa liberalization agreements was that their conclusion occurred during the period of “enlargement fatigue.” In the 2010s, most West- ern Balkan countries received candidate status, and some even started negotiating membership (Montenegro, Serbia). Still, within the EU, the time for enlargement was not yet ripe. Many thought that the EU had not digested the enlargements of the 2000s and that institutional functioning was becoming more complicated with 27 or 28 members. Fears of uncontrolled enlargement took precedence over geopolitical ambition, and the approach became minimalistic.

Thus, in the final stretch of negotiations on the AA text between the EU and Georgia, a fierce battle took place over the evocation of the European perspective in the treaty pre- amble. Substantial resistance to anything that could have even remotely given the hope of enlargement came from the major capitals (Berlin, Paris). Several rounds of negotiations on each comma resulted in a rather vague formulation about “political association and economic integration,” acknowledging “the European aspirations and European choice of Georgia” and recognizing that Georgia was an “Eastern European country.

With the entry into force of the AA, the DCFTA, and visa liberalization, the relations of Brussels with its Eastern partners followed a period of creativity breakdown. Enlargement was often portrayed as the root of numerous problems in many member states, with politicians frequently presenting it as a convenient scapegoat for various issues.

Bidzina Ivanishvili, a Georgian billionaire with Russian connections, and his Georgian Dream party came to power amidst this con- text. Unlike the previous ruling party, which started to annoy many European leaders with its overflowing activism and the strong desire to accelerate European integration, the “temperance” of the new ruling party and its “middle” position between the West and Russia found a positive echo in Europe, too tired of enlargement and eager to find a lasting modus vivendi with Moscow.

The first foreign policy statements of Ivanishvili about the non-existence of threats from Russia (“I don't believe that Russia's strategy is to occupy its neighbors’ territories”) and the fascination with Armenia’s foreign policy positioning (“Armenia's policy towards NATO and Russia is a good example for Georgia”) were not considered as particularly problematic by the Europeans at that time.

Before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and even shortly after, the enlargement file remained politically frozen. The EU calmly followed a bureaucratic enlargement routine by emphasizing the necessity to strictly comply with the spirit and letter of the membership criteria. As objectively no candidate or aspiring country met the criteria, the EU was poised to remain passive on enlargement for many years and possibly even decades.

Finally, in the spring of 2022, Ukrainian resistance and the demonstration that it could survive and even prevail against Moscow radically changed the situation. There was an apparent shift in attitude among the three European leaders (Macron, Scholtz, Draghi) following their joint visit to Kyiv in the summer of 2022. Macron recited a true profession of faith in favor of enlargement in his significant GLOBSEC Bratislava speech in Spring 2023. Thanks to the Ukrainian resistance, a traditional champion of non-enlargement, France made its aggiornamento.

Georgian government's lack of enthusiasm for Europe and its hesitancy to implement essential reforms are outweighed by geopolitical factors.

Within this scenario, the current Georgian government's lack of enthusiasm for Europe and its hesitancy to implement essential reforms are outweighed by geopolitical factors. The determined spirit of the Georgian people further bolsters these considerations. The favorable recommendation by the Commission was issued despite the actions of the Georgian Dream government rather than because of them.

How to avoid a post-candidate status failure

Was the Commission right to give a positive recommendation to Georgia's candidate status in November 2023 when its government did not deserve it and adopted a series of measures that knowingly went against the recommendations? Is it wise to continue the path of enlargement with a Georgian Dream taking up the “pinnacles” of Russian propaganda on the war in Ukraine, the “moral decay of Europe,” and its “crisis of values?” Should Brussels reward a government that seeks candidate status solely for internal political use and has no real intention of adopting reforms, as the latter would directly threaten its monopoly on political power, its domination in media, and its control of the judiciary? Is the EU not making the same mistake as in the case of Serbia, a candidate country since 2012 and in membership negotiations since 2015, but in apparent decline in terms of compliance with EU criteria of democracy, the rule of law, the fight against corruption and the alignment with EU foreign policy decisions?

The subject of EU enlargement can be viewed through two prisms: geopolitical and transformational.

The subject of EU enlargement can be viewed through two prisms: geopolitical and trans- formational. That is to say, either enlargement happens because there is a geopolitical imperative or because the aspiring state has successfully transformed its political, economic, and social systems, adopted the values of the EU, and led a foreign policy compatible with that of the Union. The new wave of enlargement is geopolitical, which is very good news. Without geopolitics, Georgia's accession to theEU would be impossible in the visible future. But this geopolitical/transformational dichotomy becomes irrelevant if no sign of transformation and backsliding of reforms blocks the geopolitical momentum and causes the failure of the enlargement process.

In this respect, the comparison of Georgia with Serbia can be interesting. Serbia received candidate status from the European Council in October 2012, and the first inter- governmental conference that launched the negotiations took place in January 2014. Nearly three-quarters of the 35 chapters are open, and two have been negotiated and temporarily closed. However, after more than ten years of talks, the political situation in Serbia has evolved in the wrong direction. The Serbian political system is considered a “competitive authoritarian,” meaning it is formally pluralist, but the protagonists are not equal. The main Serbian media outlets are generally close to the ruling party, and opponents have little or no access to them. Public sector employees are encouraged and even forced to vote for the ruling party. The Serbian opposition considers that the elections in the country are unwinnable given the conspiracy of the ruling party's interests and economic and criminal circles. Freedom House believes that Serbia is no longer a democracy but a “hybrid regime.” A law aimed at restricting the activities of NGOs and the independent media was adopted in July 2020. In addition, the country is developing solid relations with forces hostile to Europe, notably with Putin's Russia, and has signed free trade agreements with China, agreements which the EU considers to be difficult to reconcile with the economic integration of Serbia with the EU. Those who know Georgia will see many similarities.

Serbia does not follow the EU’s sanctions on Russia and, conversely, de facto participates in circumventing them. Its alignment rate with EU foreign policy is under 50 % (the same indicator is above 90% in the case of Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Albania) even though the country is the largest recipient of EU funds.

Serbian experience can help us understand the risks for Georgia. Letting go of reforms and refusing the transformative aspect of the accession process will ultimately cause the strengthening of authoritarianism and establishing an illiberal regime that will eventually move the country away from, and not closer to, Europe.

The illiberal regime's priority is power conservation, so this imperative is incompatible with European integration. On the contrary, the latter becomes the main threat, and consequently, the regime is obliged to attack Europe and its values through propaganda tools, thus undermining public support for the EU. This is the final stage of the process, where the circle is complete. According to the latest polls, only around 20% of Serbs view the EU positively, and only a third of the population favor joining the Union. In a way, Serbia is following the path already taken by Turkey, the oldest candidate and neighbor to have started accession negotiations. Once very favorably disposed towards the EU, with a majority of the population fervently in favor of membership (still 46-48% in the 2000s), Turkey today seems the furthest from the EU in the history of relations between Brussels and Ankara. Many even believe that the process is beyond repair and dead.

Once again, Serbia’s and Turkey's paths contain many specificities. For example, Islam and European states’ skepticism towards Turkey are non-negligible factors. The same applies to a violent confrontation in the 1990s between Serbia and NATO, of which most EU states are also members.

The Serbian and Turkish examples should put the EU on alert with Georgia, which was off to a perfect start, but its illiberal and authoritarian turn is jeopardizing its membership bid.

The Serbian and Turkish examples should put the EU on alert with Georgia, which was off to a perfect start, but its illiberal and authoritarian turn is jeopardizing its member- ship bid. Georgia is yet to arrive there, though. Even if the current leadership in Tbilisi is at least as illiberal and undemocratic as in Belgrade, the critical asset of the Georgian candidacy is its public opinion, which, despite the anti-EU propaganda often disseminated by the pro-government media, remains firmly anchored in favor of the EU. This temporary asset may progressively dis- appear if the government keeps methodically destroying the foundations of pro-EU feelings among citizens.

The recommendation by the Commission to grant Georgia candidate status for member- ship, which is anticipated to be finalized by the European Council in December, rep- resents a positive step. If the EU strategically positions Georgia on the favorable side of the emerging geopolitical divide despite its “different geography,” such a move should be met with resounding approval. However, the EU must maintain a transformational approach to its enlargement policy, ensuring that stringent conditions are upheld. Providing unconditional support to a government that desires the status of a candidate without a commitment to European values could lead to severe repercussions.

The Commission's evaluation has highlighted the importance of engaging Georgian civil society and the political opposition. The EU has set a clear expectation that candidate status for Georgia is contingent upon meeting specific conditions and beginning or completing significant reforms. EU messages are loud and clear: the government's strategy of deflecting blame on to Brussels for infringing upon national sovereignty is unlikely to find traction with public opinion. Conversely, vagueness in communication allows the government to point fingers at the EU, the opposition, and civil society for hindering the process of European integration. By conveying explicit messages and delineating responsibilities, the Georgian Dream could alienate its pro-European voter base, which is substantial. If European institutions precisely attribute the accountability for integration setbacks, the fear of losing the pro-European segment of Georgian Dream supporters, including civil servants, could pressure the party's leaders.

Conclusion

Three main elements stand out when examining the factors affecting the EU's decision to enlarge. Geopolitical considerations often take precedence, followed by the level of public support and the extent to which a country aligns with the EU's Copenhagen Criteria, encompassing democratic principles, the rule of law, a functioning market economy, and adherence to EU laws and regulations. This alignment is also regarded as a transformative factor, with geopolitics frequently being the primary catalyst for expansion. However, a notable gap exists be- tween the rhetoric surrounding “geopolitical enlargement” and the reform efforts, especially in Georgia's case.

The experience of EU-Georgia relations illustrates that a pro-European stance and a desire for transformation through reforms are insufficient for rapid progression toward EU membership without a strong geopolitical drive. Currently, Georgia lags behind its Eastern European counterparts in its enthusiasm for the EU, but this does not rule out its candidacy. The EU may relax its criteria when geopolitical needs, backed by public support, call for it.

The Georgian government may exploit its candidate status and the negotiation process to entrench its power rather than genuinely integrate with the EU.

Nonetheless, there are inherent dangers in offering commitments to an essentially Eurosceptic government. If the EU does not adhere to strict conditionalities and a transparent dialogue about responsibilities for a failure to meet objectives, the Georgian government may exploit its candidate status and the negotiation process to entrench its power rather than genuinely integrate with the EU. This could lead to establishing an illiberal regime, jeopardizing the country's EU membership prospects. The EU has the financial and administrative means to further the enlargement's transformative goals and, if faced with resistance from the national authorities, bolster society and ensure trans- parent electoral processes, particularly looking ahead to the pivotal 2024 elections.

It does not matter if some good things occur in the form of the irony of history; the most important thing is to seize the opportunity and achieve profoundly positive societal changes. After all, according to Emile Cioran, the “history of the whole of mankind is irony on the move”.