Can Targeted Sanctions Set the Georgian Dream on Fire?

“I don't see any problem. I don't expect any sanctions or for someone to be sanctioned (...). All this is not serious; it's just ridiculous.” “The sanctions are not a problem; everything will change and be settled. There will be a different world and Europe soon.” These statements belong to Kakha Kaladze, Mayor of Tbilisi, and the current Secretary General of the Georgian Dream. The two statements were made six months apart in June and December 2024; that is, before the fraudulent elections on 26 October, the Georgian Dream's decision to suspend negotiations with the EU on 28 November, and after the announcement of the first European and American sanctions.

How Did We Get Here?

Unlike Kaladze, a footballer-turned-mayor with limited knowledge of international relations, Ivanishvili—the true decision-maker in Georgia—was well aware of the path he was steering the country toward and had long been preparing for international sanctions. On December 30, 2023, upon announcing his second official return to politics as Honorary Chairman of Georgian Dream (GD), he claimed to be “already de facto under sanctions,” citing his lawsuit against Credit Suisse, which had frozen approximately USD 500 million of his assets, as supposed proof. His conspiracy theory—that Credit Suisse acted on orders from the U.S. government—became a central narrative for the ruling party and a focal point of Georgia’s foreign policy.

During his visit to Tbilisi in May 2024, Jim O’Brien, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, was boycotted by Ivanishvili but met with the oligarch’s Prime Minister, Irakli Kobakhidze. O’Brien could barely conceal his astonishment when Kobakhidze told journalists he had shared “only 30%” of what he knew about the so-called global war party. In response, the American diplomat remarked, “At this stage, there is no sanction on him (Ivanishvili). The fact that such an influential person is so ill-informed is both disappointing and shocking.”

A Transparency International Georgia study revealed that Ivanishvili owns dozens of offshore companies in jurisdictions like Panama, the Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands.

Shortly after passing the “foreign agents” law in May 2024, the Georgian Dream-controlled parliament rushed through legislation facilitating the repatriation of offshore funds. These tax code amendments granted exemptions not only for offshore financial assets but also for non-financial holdings such as yachts and aircraft brought into Georgia. The move was clearly driven by Ivanishvili’s growing concerns over impending Western sanctions. A Transparency International Georgia study revealed that Ivanishvili owns dozens of offshore companies in jurisdictions like Panama, the Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands. Since December 2024, he has rapidly transferred funds into eight newly registered shareholding companies in Georgia, held in the names of his family members.

Western sanctions—visa bans, asset freezes, and the blacklisting of individuals connected to the Georgian regime under the Magnitsky Act—are steadily becoming a reality. Just a year ago, this seemed unlikely, as the government was still basking in the achievement of EU candidate status while claiming to have preserved its “dignity,” a euphemism for refusing to meet Brussels’ conditions.

Anticipating Western sanctions after Georgia’s geopolitical shift and crackdown on protests, Ivanishvili sought a pretext to deflect blame for breaking with the West. He framed his legal dispute with Credit Suisse as U.S.-orchestrated pressure, despite winning in arbitration courts—making his conspiracy claims absurd. To justify state involvement, he recast the issue as a broader Western plot to blackmail him into dragging Georgia into war with Russia. In a quasi-Thomistic co-substantiality fusion, he equated his personal financial defense with safeguarding the Georgian nation, presenting himself as a martyr punished not for state capture and repression but for resisting Western-imposed war and moral decay, including same-sex marriage.

It remains unclear whether Ivanishvili orchestrated this scheme entirely to justify his growing alignment with Moscow, genuinely believes in the conspiracy, or has been manipulated by Russia. However, the undeniable reality is that all of Georgia is now trapped in this surreal narrative.

Where Does Georgia Stand Now?

While discussions now center on Western sanctions, historically, it was Moscow that used coercive measures to exert influence, even before Mikheil Saakashvili’s pro-Western government. Under Shevardnadze’s presidency in 2000, Russia introduced a visa regime for Georgian citizens while exempting those in the Kremlin-backed separatist regions of Abkhazia and Tskhinvali. Around the same time, Moscow also attempted to block remittance transfers from Georgian emigrants, a move the Russian ambassador, Felix Stanevski, described as the end of “Russian economic aid” to Georgia.

By 2006, under Saakashvili’s leadership, the Russian government imposed an embargo on Georgian agricultural products, dealing a severe blow to the wine industry, which heavily depended on the Russian market. This embargo remained in place until 2013 when the Georgian Dream came to power. That same year, Moscow forcibly deported 4,634 Georgian citizens, indiscriminately expelling both legal and undocumented residents. Many were transported on cargo planes unfit for human passengers. In 2019, the European Court of Human Rights ruled against Russia, ordering compensation for the victims, citing violations of their rights and the harm they endured.

It would have been unthinkable just a few years ago that Georgia, once a victim of Russian sanctions and military aggression, would now be facing Western sanctions. This paradoxical trajectory is largely the result of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s “inimitable style” and political strategy. In December 2023, Georgia secured EU candidate status, even though then-Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili framed the EU as an oppressor. After celebrating this achievement, the Georgian Dream swiftly undermined it by adopting laws that directly contradicted the EU’s fundamental values, sabotaging Georgia’s path toward integration. By spring 2024, the ruling party had escalated an aggressive anti-Western campaign, amplifying narratives about the “global war party” while simultaneously boasting about candidate status to confuse voters. Following the fraudulent 26 October elections, the Georgian Dream formally halted EU integration and accelerated its transformation into a Belarus-style autocracy. Repression intensified, with draconian laws modeled after Russian legislation, widespread political persecution, and escalating violence. Georgia now nears over one hundred political prisoners, as international watchdogs, including Amnesty International, report systematic torture and human rights abuses.

In response to Georgia’s rapid slide into authoritarianism, the EU has so far only agreed to suspend visa-free travel for holders of Georgian diplomatic passports. Broader sanctions remain stalled due to opposition from Hungary and, to a lesser extent, Slovakia—both seen as key defenders of Ivanishvili’s regime within the EU. Budapest has even refused to implement the suspension of diplomatic visa-free travel. However, several EU member states, including the Baltic States, Germany, and the Czech Republic, have taken unilateral action, imposing travel bans and asset freezes on Georgian officials. Under Schengen rules, such bans can be extended across the bloc at the discretion of individual member states.

Beyond the EU, the UK has sanctioned several Georgian officials responsible for repression, barring them from entry and freezing their assets. A group of British MPs has also pushed for sanctions against Ivanishvili and his companies, with some advocating for his frozen assets to be repurposed to support democracy in Georgia. Additionally, Irakli Rukhadze, owner of the pro-government Imedi TV, is under scrutiny as his company and assets are registered in the UK.

The United States has taken even stronger measures, beginning in 2023 by sanctioning corrupt Georgian judges and expanding penalties to include dozens of top officials, culminating in the blacklisting of Ivanishvili himself. Sanctioned under the Russian Harmful Activities Sanctions regime (EO 14024), he is accused of enabling human rights abuses and obstructing Georgia’s democratic and pro-European path to serve Russian interests. In December 2024, several high-ranking officials from the Ministry of the Interior, including Minister Gomelauri, were added to the Magnitsky list, which targets individuals involved in severe human rights violations.

What Type of Sanctions for the Georgian Dream?

Sanctions against Ivanishvili are unfolding as a self-fulfilling prophecy, with Georgian civil society urging Washington, Brussels, and other Western capitals to accelerate their implementation. However, some in the West remain skeptical about their effectiveness in dismantling authoritarian regimes. They cite long-standing examples such as Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, and Russia, where despite economic hardship, dictatorships have endured.

Broad economic sanctions tend to harm ordinary citizens more than ruling elites, who often find ways to bypass restrictions through illicit financial networks.

Critics argue that sanctions can backfire by reinforcing authoritarian narratives, with regimes using propaganda to portray foreign pressure as a conspiracy against national sovereignty. Additionally, broad economic sanctions tend to harm ordinary citizens more than ruling elites, who often find ways to bypass restrictions through illicit financial networks.

Targeting an entire country’s economy can be counterproductive, as seen in Iran, Venezuela, and Cuba, where sanctions have led to widespread poverty, food and healthcare crises, and deteriorating infrastructure. Opponents frequently reference Iraq under Saddam Hussein, where sanctions were blamed for soaring child mortality due to malnutrition and collapsing healthcare—though later studies suggested some figures were manipulated to discredit the U.S. Regardless, humanitarian concerns continue to fuel doubts about the effectiveness of economic sanctions.

Economic sanctions often increase discontent with authoritarian regimes but rarely succeed in toppling them. Venezuela exemplifies this: despite an unprecedented economic collapse—its GDP shrinking by 8.5 times between 2012 and 2020 and inflation hitting 63,374% in 2018—the Maduro regime remains in power. With 91% of the population in poverty, the crisis is partially offset by mass emigration (7 million people) and continued remittances. In some cases, economic hardship even strengthens authoritarian control. North Korea deliberately starves its population to suppress dissent, while Venezuela’s CLAP food distribution program ensures loyalty by selectively supplying necessities to regime supporters.

Meanwhile, corrupt elites thrive under sanctions, exploiting smuggling and illicit trade networks, as seen with Venezuela’s military and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. Propaganda further shields regimes, redirecting blame to Western sanctions. Cuba and Iran have long used anti-American rhetoric to justify economic struggles, a tactic the Georgian Dream is likely to adopt, portraying EU measures as an attack on the Georgian people rather than the regime.

Suspending Georgia’s visa-free travel with Schengen countries could have unpredictable effects—potentially fueling anti-regime sentiment or reinforcing GD’s narrative of Western “humiliation.” Instead, targeted sanctions against those responsible for repression—officials, judges, and regime-aligned businessmen—would be more effective. With Georgia’s population overwhelmingly pro-Western, broad punitive measures risk alienating ordinary citizens, while precise action against the ruling elite could help weaken the regime without undermining public support for the EU.

Without consequences, the ruling party will continue deceiving segments of the population by claiming there is no real break with the West.

Failing to sanction the Georgian Dream is not a neutral stance—it is a policy choice with serious consequences. Without consequences, the ruling party will continue deceiving segments of the population by claiming there is no real break with the West. This narrative helps retain supporters who are uncomfortable with openly pro-Russian policies. Sanctions would make it clear: the Georgian Dream and Ivanishvili are anti-European and hostile to EU values.

For others, the absence of sanctions reinforces the perception of Western weakness, indecision, and decline—emboldening Ivanishvili to escalate repression against the opposition, civil society, and independent media. Moreover, inaction would damage the EU and the U.S. standing among Georgia’s pro-Western citizens, raising doubts about their commitment to defending democratic values. It is already painful for many to watch the ruling elite sabotage Georgia’s European future while enjoying the privileges of the West—owning property, educating their children, and vacationing there.

The synergy between domestic resistance and external pressure is essential for success—creating a necessary cycle of momentum against authoritarian entrenchment.

Sanctions also serve as a critical show of international solidarity with the tens of thousands of Georgians protesting for democracy. These demonstrators rely on Western support, knowing that internal mobilization alone may not be enough. Every EU or U.S. sanction against a Georgian Dream official or enabler of repression fuels hope and strengthens the movement. The synergy between domestic resistance and external pressure is essential for success—creating a necessary cycle of momentum against authoritarian entrenchment.

Who Should Be Sanctioned?

Targeted sanctions against key Georgian officials could be highly effective. Ivanishvili’s authoritarian regime relies on three key pillars: a bureaucracy fully absorbed by the ruling party, a corrupt judiciary and law enforcement under his control, and a powerful propaganda machine led by outlets like Imedi TV, PosTV, the Georgian Public Broadcaster, and Rustavi2. Unless these pillars are weakened, the regime will remain resilient against internal dissent.

Unlike Ivanishvili, Georgian Dream elites—ministers, MPs, judges, high-ranking police officers, diplomats, and affiliated businessmen—are more vulnerable to Western sanctions. They hold no real political influence or say in Georgia’s foreign policy, serving solely to advance Ivanishvili’s personal interests in exchange for financial benefits. Many have built their lives around the West, sending their children to study abroad and investing in European assets, despite lacking any ideological commitment beyond material gain. For most Georgians under 50, Russia is not a viable alternative, and even former Soviet-era officials have families unwilling to relocate to Russia, Iran, or China.

Until recently, Western governments were relatively tolerant, allowing figures like Irakli Rukhadze, owner of the main pro-government TV network, to register businesses in the UK and the Netherlands while simultaneously spreading anti-Western propaganda.

This dependency on Western financial and social privileges makes them more susceptible to targeted pressure. They have carried out Ivanishvili’s increasingly pro-Russian policies without expecting a full break with the West. Until recently, Western governments were relatively tolerant, allowing figures like Irakli Rukhadze, owner of the main pro-government TV network, to register businesses in the UK and the Netherlands while simultaneously spreading anti-Western propaganda. Stripping them of these privileges would expose their hypocrisy and significantly destabilize the regime’s internal cohesion.

All of this is to say that Georgian Dream political, bureaucratic, and business elites were not expecting such a radical break with the West. Even after the adoption of the Russian laws and tensions with the EU and the US, these elites were privately communicating to Western diplomats that all of this was temporary and due to the electoral campaign and sooner or later it would be "back to business as usual."

As previously noted, key figures within the Georgian Dream do not make significant decisions. The shift away from the West and the forced transition toward the Russian-Belarusian model was solely Ivanishvili’s decision—likely under Russian pressure—with the entire system following his lead. At 69, having spent much of his life in Russia, Ivanishvili is as much Russian as he is Georgian. His business career was shaped in Russia, giving him extensive ties and experience there, unlike most Georgians. For years, he even adopted the Russianized version of his name, Boris, by which he is still known in Russian oligarchic circles. Unlike his associates, a return to Russia would not be a dramatic shift for him but rather a return to familiar ground. His past involvement in Russian politics, including financing General Lebed’s career, underscores his deep connections.

At this stage, the regime’s internal cohesion is its greatest vulnerability, and personal sanctions—or even their credible threat—could play a decisive role in accelerating its erosion.

In contrast, Georgian Dream politicians, civil servants, and business elites—who have built their lives around Western access—are far more alarmed at the prospect of EU and U.S. sanctions. The possibility of visa bans and asset freezes is already causing unease, leading to growing internal tensions. Business figures who previously thrived under government protection have begun to voice concerns, as seen in a December meeting between entrepreneurs and de facto Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze. Though many of them were staunch Georgian Dream supporters, the looming threat of sanctions has, for the first time, made them question the government’s trajectory. At this stage, the regime’s internal cohesion is its greatest vulnerability, and personal sanctions—or even their credible threat—could play a decisive role in accelerating its erosion.

Despite their corruption and lack of principles, the Georgian Dream elite still sees Europe—not Russia or China—as their horizon. There are, of course, exceptions, such as Otar Partskhaladze, the former Prosecutor General who now oversees the business community on Ivanishvili’s behalf. Sanctioned by the United States for his ties to Russian intelligence, Partskhaladze has been actively working to shift business networks toward Russia. However, his efforts have yet to yield full success, as many within the elite remain reluctant to fully sever their ties with the West.

Ivanishvili may one day echo Zimbabwe’s former dictator Robert Mugabe, declaring, “We don’t mind sanctions banning us from Europe. We are not Europeans!” But if that moment comes, how will his loyal elites react? Are they truly ready to sever ties with the West and embrace full isolation?

Dictators despise sanctions, yet they go to great lengths to downplay their impact—an effort that ironically confirms their effectiveness. In 2014, following the first wave of Western sanctions after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Sergey Lavrov insisted, “Russia will not only survive but will come out much stronger… Sanctions are a sign of irritation, not a serious policy tool.” Putin echoed this dismissive stance, telling CBS’s Charlie Rose, “If someone prefers to use sanctions, they are welcome to do so. But sanctions are temporary measures… illegal under international law. Tell me where they have ever been effective. The answer is nowhere.”

If sanctions are truly ineffective (and supposedly illegal), why does Putin’s Russia repeatedly use them to punish defiant neighbors? Moscow has imposed sanctions on Georgia, Ukraine, the Baltic states, Poland, and Moldova, among others. When Georgian Dream officials claim they are unfazed by sanctions, it is likely the opposite.

Following the U.S. decision to sanction Ivanishvili, the regime’s de facto Prime Minister, Irakli Kobakhidze, rushed to frame it as a badge of honor, declaring, “In reality, it is an award, a prize for defending the national interests of our country.” One might suspect that many Georgians would not mind if their unofficial ruler received more such “awards” from the West.

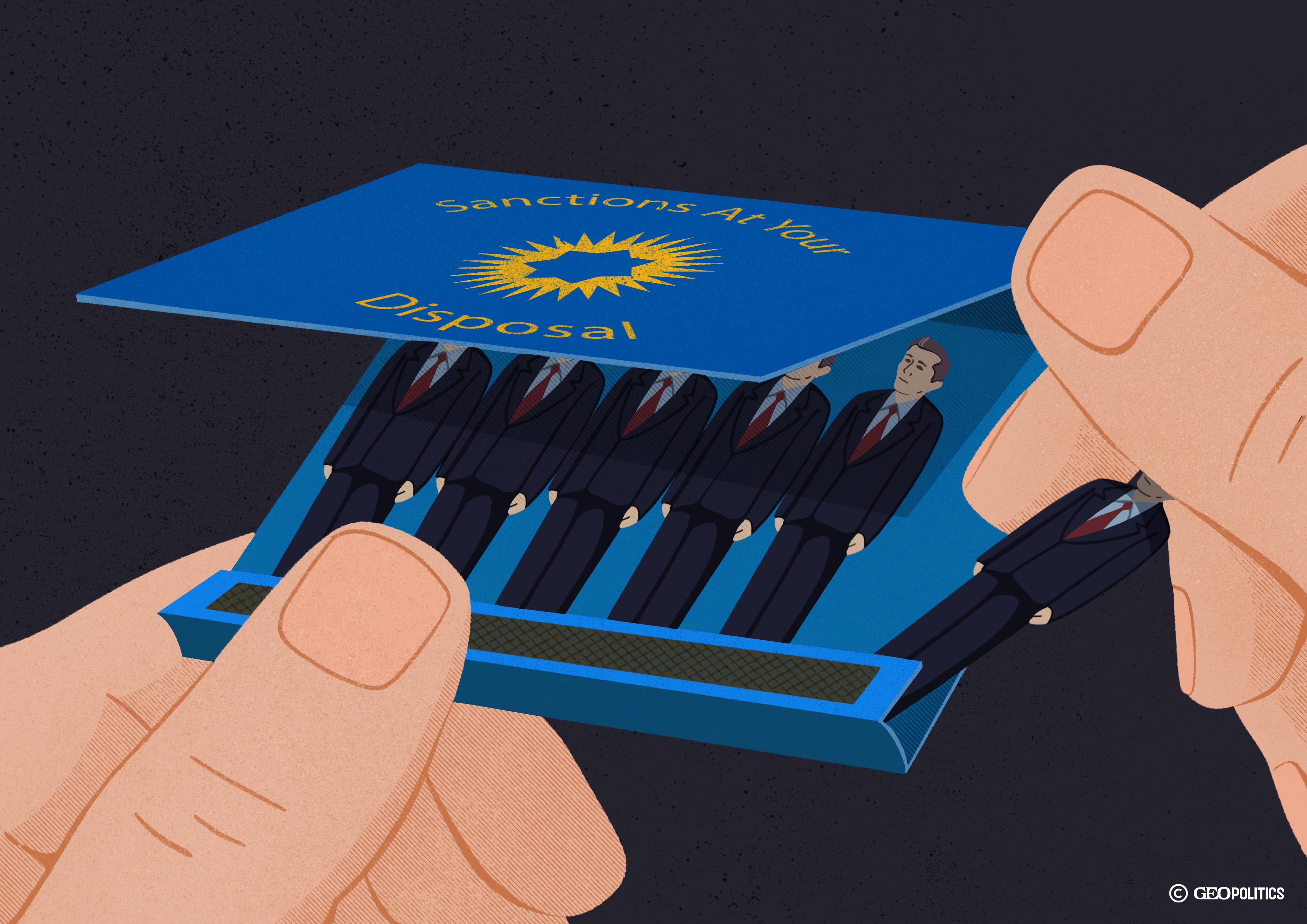

Western sanctions are already igniting cracks within Georgian Dream’s ruling elite. Once confident in their loyalty to Ivanishvili, they now see their assets and Western access at risk. Many assumed tensions with Brussels and Washington were fleeting, but as targeted measures loom, their blind allegiance is faltering. The West must strike the Ivanishvili matchstick—once lit, the fire will spread, igniting the entire Georgian Dream box. As the cost of loyalty rises, business leaders and bureaucrats will scramble to save themselves, accelerating the regime’s collapse from within.