The Backsliding of Georgia’s European Dream

On November 28, the Georgian Dream (GD) declared that it would remove the issue of accession negotiations from the EU-Georgia bilateral agenda, effectively ending Georgia’s EU membership bid during its tenure, as well as during the tenure of the current European Commission. While other authors in this volume took a closer look at the implications of this decision and the events that followed GD’s rejection of the EU path, we will look into the current relations between the EU and Georgia regarding fulfilling accession criteria and preparing for membership. This is particularly important since the GD leaders and talking heads have been arguing that in fact, the Georgian leadership would continue implementing the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA).

On October 30, 2024, the European Commission published its annual communication on enlargement policy and accompanying country reports. For Georgia, this marked the release of its second report under the revised accession methodology introduced in 2020. The findings paint a troubling picture: while Moldova and Ukraine are advancing rapidly toward EU accession, Georgia is stagnating—and, in some cases, backsliding.

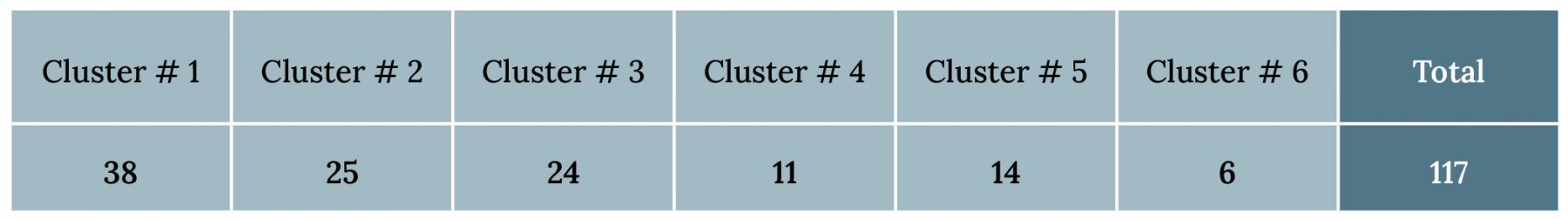

The report evaluates 33 policy areas, or chapters, grouped into six clusters: (1) Fundamentals; (2) Internal Market; (3) Competitiveness and Inclusive Growth; (4) Green Agenda and sustainable connectivity; (5) Resources, agriculture, and cohesion; (6) External relations.

Similar reports were also published for Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Kosovo (not recognized by 5 EU member states and Serbia) as well as for Ukraine, Moldova, and Türkiye. Although the EU’s General Affairs Council declared in June 2018 that Türkiye’s accession process had “effectively come to a standstill”—with no further chapters to be opened or closed and no progress on modernizing the EU-Türkiye Customs Union—the EU continues to evaluate Türkiye’s integration progress and includes it in its annual assessments.

The EU’s enlargement policy communication offered an intriguing indication regarding the timeline for future enlargement. Specifically, the European Commission conveyed an encouraging message to Montenegro, highlighting that “the government of Montenegro signaled its objective to close accession negotiations by the end of 2026.” The Commission expressed its readiness to support this ambitious goal by proposing the provisional closure of additional chapters by the end of 2024 and outlining a substantial agenda for 2025, provided the necessary conditions were fulfilled.

The European Union evaluates a country’s level of preparation using a five-grade scale: (a) early stage of preparation, (b) some level of preparation, (c) moderately prepared, (d) good level of preparation, and (e) well advanced. For measuring progress, it uses four levels: (a) backsliding, (b) no progress, (c) limited progress, (d) some progress, and (e) very good progress. Additionally, the report outlines specific recommendations the country should implement in the coming year. The enlargement report serves as a critical tool—an “X-ray” of sorts—highlighting a country’s challenges and identifying the policy areas requiring attention to advance toward EU membership. These recommendations are vital for ensuring continued progress toward European integration.

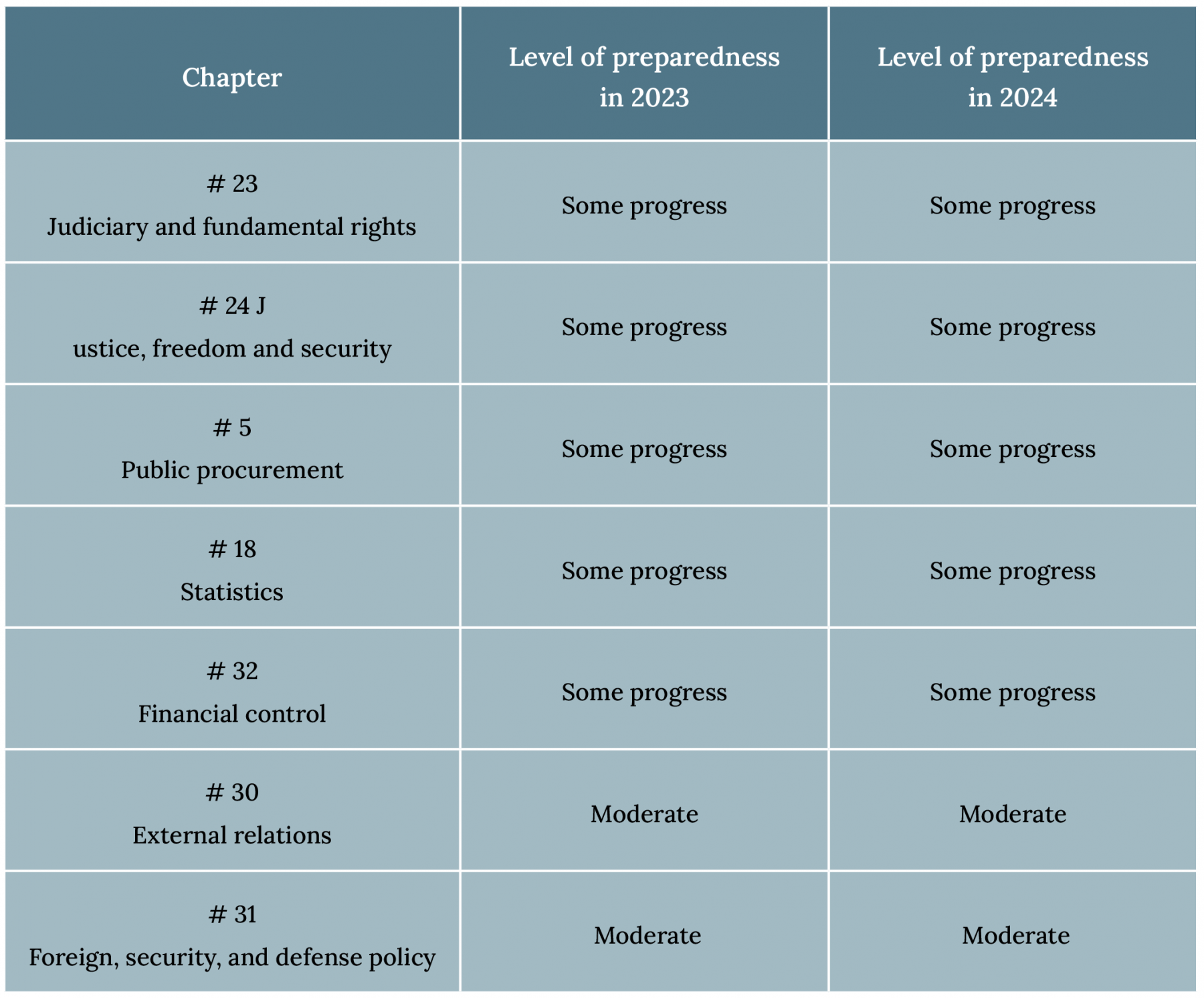

How the EU views Georgia

On June 27, 2024, the European Union effectively decided to pause Georgia’s EU accession process. Nevertheless, much like in the case of Türkiye, the EU continues to monitor the performance of candidate countries and publishes annual enlargement reports. A key area of focus in these reports is the “Fundamentals” cluster, which comprises five critical policy fields: Chapter 23 (Judiciary and Fundamental Rights), Chapter 24 (Justice, Freedom, and Security), Chapter 5 (Public Procurement), Chapter 18 (Statistics), and Chapter 32 (Financial Control).

This cluster holds exceptional importance and can be described as the “engine” of the accession process, as progress in these areas dictates the overall pace of negotiations. According to the EU negotiation frameworks for Ukraine and Moldova, any regression in the Fundamentals cluster could result in the suspension of accession talks. Furthermore, these chapters are always the first to open and the last to close during negotiations, reflecting their central role in the EU accession process.

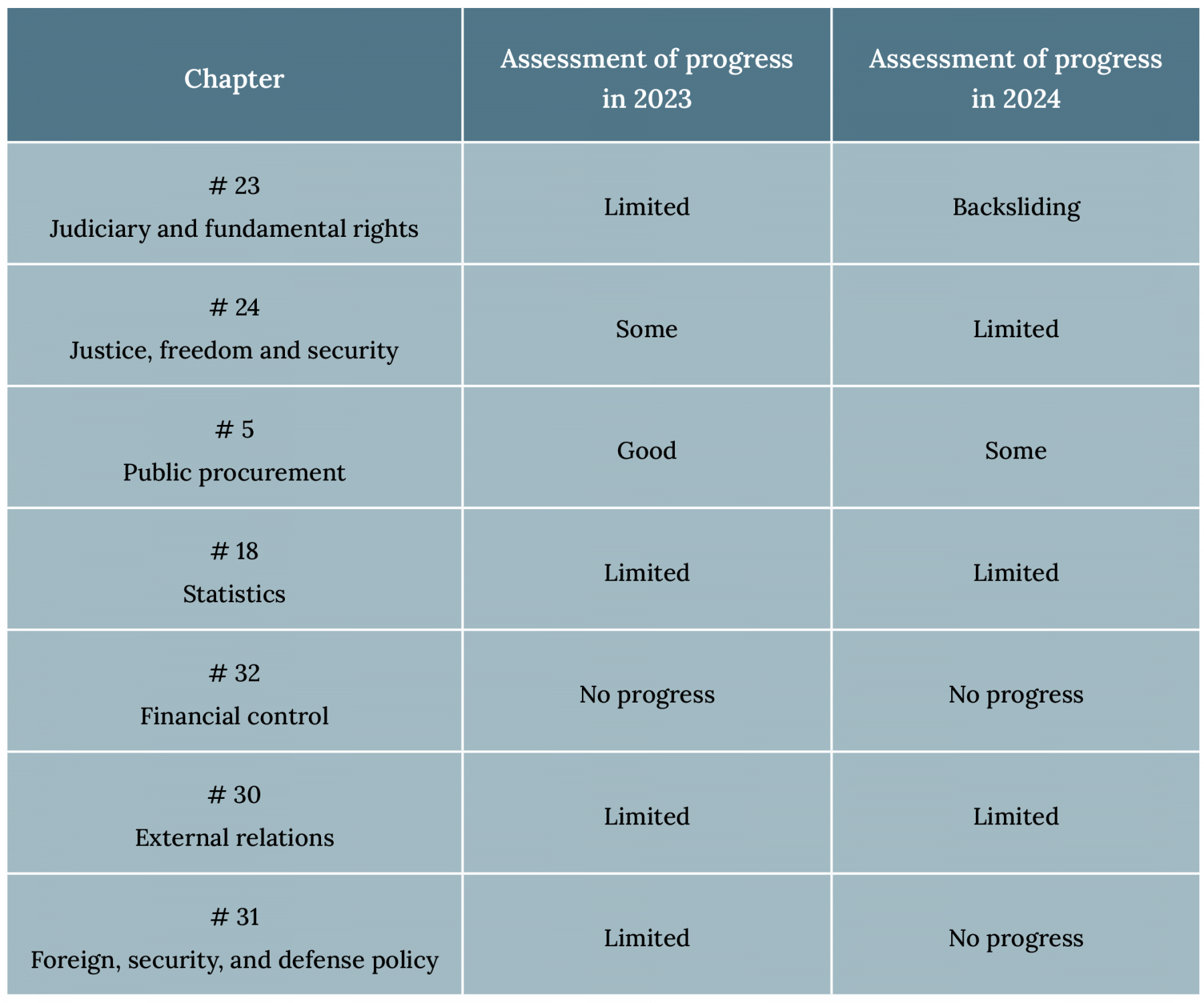

The EU has assessed Georgia as being at “some level of preparation " in the five chapters of Cluster #1. However, when evaluating progress, the EU noted that since November 2023, Georgia has been backsliding in Chapter 23 (Judiciary and Fundamental Rights). No progress was recorded for Chapter 32, limited progress for Chapters 24 and 18, and some progress for Chapter 5.

Georgia received 117 recommendations that the authorities must address by the following EU assessment in autumn 2025. This means the EU’s evaluation will focus not only on the fulfillment of the 9-step criteria but also on the additional recommendations outlined in each chapter.

Georgia received 117 recommendations that the authorities must address by the following EU assessment in autumn 2025. This means the EU’s evaluation will focus not only on the fulfillment of the 9-step criteria but also on the additional recommendations outlined in each chapter. Notably, 32% of these recommendations pertain to the Fundamentals cluster.

In its assessment, the EU applied the “backsliding” grade for the first time, highlighting the deteriorating state of Georgia’s judiciary, particularly in Chapter 23.

Number of recommendations by clusters that EU gave to Georgia in 2024; Source: Commission Staff Working Document; Georgia report 2024

The European Union places significant emphasis on Cluster #6, which covers Chapters 30 (External Relations) and 31 (Foreign, Security, and Defense Policy). A key focus is ensuring that candidate countries align their foreign and security policies with the EU's. As of the end of September 2024, Georgia’s alignment rate stood at 49%, indicating it is only halfway to achieving complete alignment. This marks a slight decline from 50% in 2023, though it has improved from 44% in 2022.

Georgia’s alignment challenges are underscored by its recent actions, including signing a Strategic Partnership agreement with China, which suggests that alignment with the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is not a top priority. Additionally, Georgia has suspended participation in EU crisis management missions and operations under the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP). Since June 2023, the number of direct flights between Georgia and Russia has also increased significantly.

Among EU candidate countries, only Georgia and Ukraine (due to its ongoing war) do not participate in EU crisis management missions and operations. Excluding Türkiye, Georgia’s CFSP alignment rate is the lowest among candidate countries and even lags behind Serbia, led by pro-Russian President Aleksandar Vučić.

Alignment with EU Foreign and Security Policy. State of Play among EU Candidate Countries. Source: Commission Staff Working Documents; Country reports of 2024.

A comparison between the EU enlargement reports on Georgia for 2023 and 2024 reveals that the country’s level of preparedness in the Fundamentals cluster has remained unchanged. However, in terms of progress, Georgia either regressed or showed no improvement compared to the previous year. A similar trend is observed in Chapters 30 and 31.

Source: Commission Staff Working Document; Georgia report 2024 and 2023.

Georgia made either limited progress or no progress in the Fundamentals cluster. Moreover, in one of the most critical chapters, Judiciary and Fundamental Rights, the country experienced backsliding.

Source: Commission Staff Working Document; Georgia report 2024 and 2023.

A comparison of the 2024 EU enlargement reports for Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia reveals that, since 2023, Ukraine and Moldova have shown significant progress, while Georgia has lagged behind.

A comparison of the 2024 EU enlargement reports for Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia reveals that, since 2023, Ukraine and Moldova have shown significant progress, while Georgia has lagged behind. Analyzing the reports alongside the EU’s decision to initiate accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova highlights that achieving some to a good level of progress is key—a benchmark that Georgia has yet to meet.

Using the European Stability Initiative’s (ESI) methodology and scoreboard (backsliding = 0, no progress = 1, limited progress = 2, some progress = 3, and good progress = 4), it becomes evident that Moldova and Ukraine outperformed Georgia over the past year. In the seven key chapters assessed, Georgia experienced backsliding or no progress in three areas, limited progress in three others, and only managed some progress in one.

The European Union has outlined 117 recommendations for the Georgian authorities to implement. These recommendations carry significant weight, as they could eventually become opening, interim, or closing benchmarks if accession negotiations with Georgia are initiated. However, given the current domestic context, some of these recommendations may prove challenging for Georgia.

One notable recommendation is for Georgia to align its national legislation with EU standards by lifting restrictions on EU nationals' acquisition of agricultural land. This poses a constitutional challenge, as Article 19 (4) of the Georgian Constitution stipulates that agricultural land, as a resource of special importance, can only be owned by the state, a self-governing unit, Georgian citizens, or associations of Georgian citizens. Exceptional cases require an organic law passed by a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

This constitutional restriction is rooted in the political platform of the ruling Georgian Dream party, which came to power in 2012 with a promise to prohibit foreigners from purchasing agricultural land in Georgia.

The European Union also advises Georgian authorities to harmonize national legislation on VAT and excise duties with the EU acquis. However, under Georgia’s Organic Law on Referendums, referendums may be held to introduce new types of national taxes—except excise taxes—or to raise the upper threshold of existing tax rates based on their type.

These recommendations from the EU must be taken seriously, as they will remain on the table until the Georgian authorities address them adequately and align with EU standards.

Falling Behind Moldova and Ukraine

Even if the Georgian Dream had not rescinded the EU accession process in November 2028, Georgia had already lost a lot of time compared to Ukraine and Moldova. This setback would have been difficult to recover even if the government had pursued a fast-track approach to implementing EU conditionalities. Meanwhile, Moldova and Ukraine have advanced significantly on the EU track, moving closer to launching accession negotiations, likely in the first half of 2025 under Poland’s rotating EU presidency. The gap between Georgia and its two neighbors has widened. Moldova, in particular, has held free and fair elections, maintained a pro-European president, and voted in favor of the referendum to enshrine EU accession in its Constitution.

The European Commission’s latest enlargement report highlighted that Georgian authorities are not genuinely committed to the EU accession process, resulting in increasingly strained and toxic relations between the two sides.

These developments have led the EU to decouple Georgia from Ukraine and Moldova and treat it as a separate case. The distinction is apparent – Kyiv and Chisinau are on a European track, while Tbilisi is not. The European Commission’s latest enlargement report highlighted that Georgian authorities are not genuinely committed to the EU accession process, resulting in increasingly strained and toxic relations between the two sides. The November 28 announcement to suspend the EU accession process until 2028 will irreversibly damage these relations.

It remains uncertain whether the EU will opt for another “Big Bang” enlargement, as it did in 2004, encompassing the Western Balkans, Ukraine, and Moldova, or pursue a more tailored, country-specific approach. What is clear, however, is that this could represent the final chapter of EU enlargement—and Georgia is in danger of being left out. The major misstep has already been made on November 28.