It’s the Foreign Policy, Stupid?!

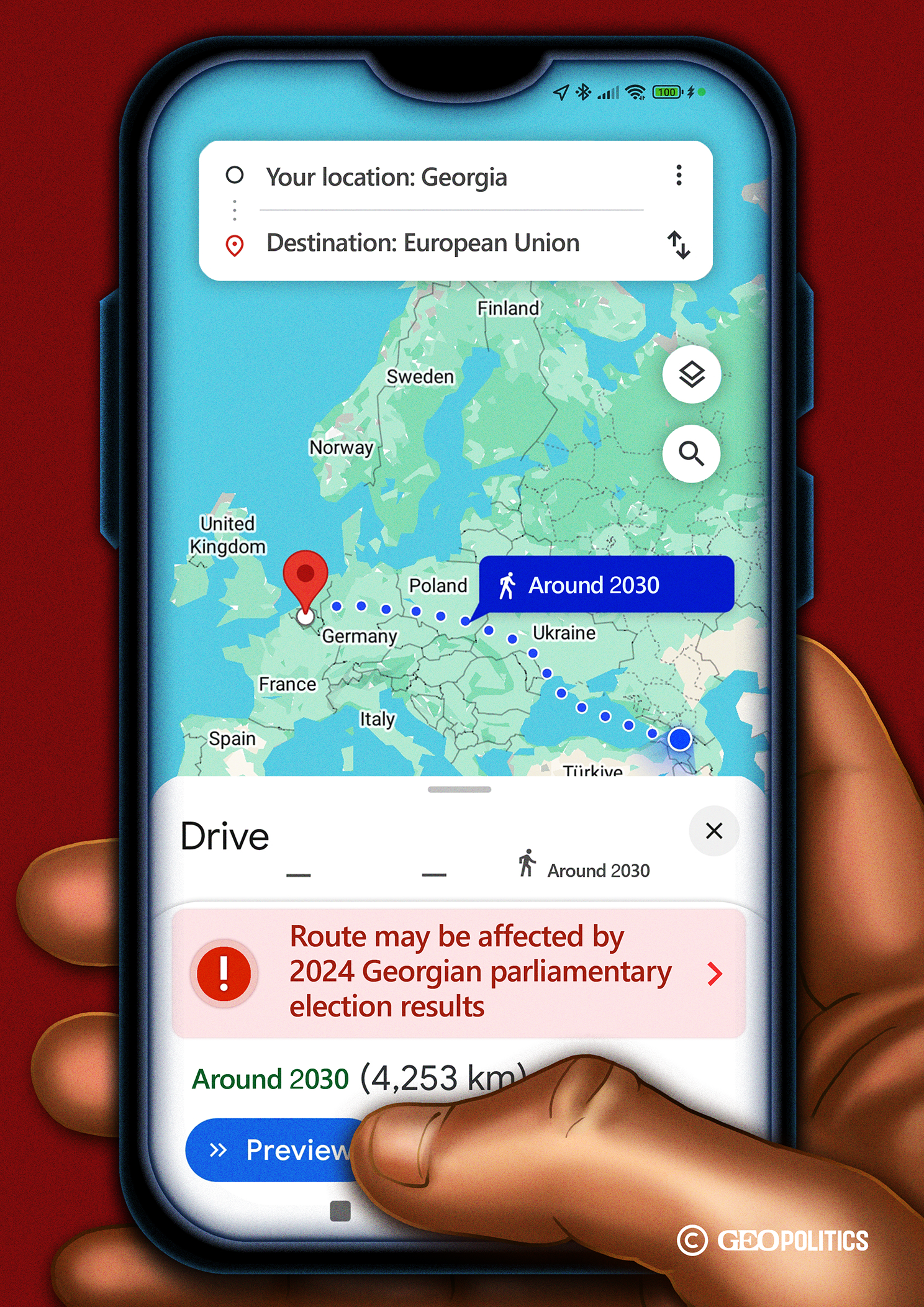

The mantra “It’s the Economy, Stupid!” coined by Bill Clinton’s campaign strategist Bill Carville during the 1992 campaign became a catchphrase denoting that what voters care about most is the economy. In the 2024 Georgian elections, however, the major pre-election debate is about the country’s foreign and security policy.

According to a recent poll, 50% of Georgians report being unemployed, 78% actively seek work, 57% of households are in debt, and 58% have a family living abroad. Despite these pressing domestic issues, probably for the first time in Georgia's recent history, geopolitics, European integration, and foreign policy have become primary election issues for the political parties.

The ruling and opposition parties agree on one thing: the general election is a referendum.

The ruling and opposition parties agree on one thing: the general election is a referendum. However, the “referendum questions” differ significantly. The opposition frames it as a choice between the European Union and Russia or between “European prosperity” and the “Russian swamp.” The ruling party, leveraging the trauma of the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia and the ongoing full-scale invasion of Ukraine, encourages voters to choose between Western interventionism and the risk of war. The Georgian Dream (GD) presents itself as the guarantor of peace, emphasizing that under its leadership, the country has experienced no wars since independence. Unlike the opposition parties, the GD campaigns on a platform of mending ties with Russia while promising to hold a “Georgian Nuremberg Trial” where the collective United National Movement (UNM), including various opposition parties, NGOs, and media, would face severe legal consequences.

The GD campaigns on a platform of mending ties with Russia while promising to hold a “Georgian Nuremberg Trial” where the collective United National Movement (UNM), including various opposition parties, NGOs, and media, would face severe legal consequences.

In this article, we look deeper at the foreign policy visions of the major parties. A detailed foreign policy-related questionnaire was sent to all five political parties/centers: the Georgian Dream, Unity – National Movement, Coalition for Change, Strong Georgia, and For Georgia. The GD and the UNM did not provide written answers; therefore, the article uses their public statements and campaign rhetoric for the analysis. The remaining three opposition parties’ written responses and public statements are combined to analyze their foreign policy visions.

The Primacy of the EU

Rhetorically, all political parties in Georgia, both the ruling and opposition, support the country’s EU accession process. All major opposition parties (except for the GD) signed the Georgian Charter, initiated by the President of Georgia, which commits the signatories to fulfill the nine points of the European Commission's 2023 recommendations. Therefore, it would be fair to say that the swift implementation of the EU’s conditionalities is a commitment the opposition parties have undertaken.

Although the Georgian Dream is mainly responsible for halting Georgia’s progress toward EU membership, it continues to assert that Georgia will join the EU on its terms and that the accession will be through a dignified process, not an EU diktat. This approach disregards the existence of EU accession Copenhagen Criteria and Article 2 of the EU Treaty, which outlines the European values that member states and candidate countries must uphold.

For the GD, the EU membership process has become a burden, but abandoning it openly would amount to political suicide.

Various polls show that public trust in the GD’s commitment to a pro-European policy is dwindling. With EU integration backed by around 80% of the population, the GD finds itself in a precarious position. While the party recognizes that fulfilling the nine steps—such as judicial reform, deoligarchization, and combating corruption—would likely lead to its loss of power due to abandoning the entrenched control it holds over the state institutions, it is also compelled to appease the electorate by paying lip service to the idea of EU accession. For the GD, the EU membership process has become a burden, but abandoning it openly would amount to political suicide. Thus, the GD’s banners, political ads, and public statements still focus on European integration but emphasize resisting EU pressure and maintaining sovereignty and independence. “With dignity to EU” – is the punchline of the Georgian Dream.

In previous elections, the Georgian Dream used to portray itself as the political force that brought Georgia closer to the European Union. During the GD's time in office, Georgia signed the Association Agreement, which includes the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), secured visa liberalization, and submitted an application for EU membership. However, a closer look reveals that negotiations on the Association Agreement and DCFTA were largely concluded before the GD came to power, with around 90% of the process already completed. The visa liberalization dialogue was initiated in 2012, before the elections, and the application for EU membership in 2022 was driven by public pressure in the wake of the Ukraine crisis. Therefore, the main talking point during the 2024 campaign is not the GD’s previous achievements on the European part but its “success” in resisting EU pressure and still achieving EU candidate status.

The main talking point during the 2024 campaign is not the GD’s previous achievements on the European part but its “success” in resisting EU pressure and still achieving EU candidate status.

At the same time, actions like pushing for a Russian-style foreign agents law, failing to implement EU-required reforms, and tilting towards Russia have limited the GD’s ability to offer substantial commitments on EU membership. The party is increasingly blending EU accession rhetoric with conservative nationalist themes, such as denouncing LGBTQI and religious minorities, framing the EU process as one that would force Georgia to surrender its sovereignty and allow Brussels to interfere in its domestic affairs.

The opposition political parties primarily view EU integration as a tool to challenge the ruling Georgian Dream.

On the other hand, the opposition political parties primarily view EU integration as a tool to challenge the ruling Georgian Dream.

The largest opposition coalition – the Unity-National Movement, mainly builds its pre-election program around the benefits that Georgian citizens will receive when the Georgian Dream is voted out of power, and EU doors reopen again for Georgia. The UNM punchline is that the GD is blocking Georgia’s EU path and access to the benefits that the EU provides.

The UNM’s symbolic pre-election artifact is a Georgian passport with the EU passport insignia. The implied message behind the Georgian EU passport is that if the GD is voted out, the new coalition government will make Georgia an EU member. This promise is too far-stretching since EU enlargement does not have deadlines. The only date on record is 2030, which was put forward by the outgoing President of the European Council, Charles Michel. Still, even that was barely shared by the EU member state leaders and other EU institutions.

The UNM also promises that defeating the GD will open access to EUR 14 billion in EU funds. The party leaders have contradictory message boxes on this topic. Some leaders openly claim that this much money will be available for Georgia from the Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III) that covers a period of 2021-2027 (coincidentally amounting to EUR 14.162 billion.) However, in reality, the EU regulation (EU) 2021/1529 establishes the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III), and its annex I defines the beneficiary countries: Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Türkiye. It does not apply to Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Other UNM leaders, however, have a more refined message, claiming that the new investments from the EU, currently suspended financial aid and flagship projects, and potential new assistance from the EU pre-accession funds would amount to EUR 14 billion. The financial timeframe, however, is not specified. In any case, even this promise is not entirely realistic, albeit resonating with the broader public that the GD is blocking the EU accession process.

The Strong Georgia political bloc, which unites four parties and movements—Lelo, For the People, Citizens, and Freedom Square—has presented its vision under the title Ilia's Way, alluding to the 19th-century liberal intellectual and statesman Ilia Chavchavadze. In aligning Georgia's foreign policy with the EU, Strong Georgia pledges to implement EU sanctions against Russia fully. To combat Russian disinformation and propaganda, the bloc plans to halt the broadcast of Russian TV channels. Additionally, they propose introducing a vetting mechanism to ensure the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, alongside filling all vacant judicial positions. These steps, in their view, will contribute to the swift implementation of the nine conditions that the EU put forward in 2023. Strong Georgia also plans to adopt a Georgia Protection Act to ensure a rapid increase in the convergence rate of Georgia’s foreign and security policy with that of the EU and Western partners.

Another political bloc, the Coalition for Change, which brings together four parties—Ahali, Girchi-More Freedom, Droa, and the Republican Party—and activists from the Future Movement, also intends to combat Russian disinformation with a more inclusive approach. Unlike Strong Georgia, the Coalition for Change proposes selectively adopting only those EU sanctions on Russia that are crucial for Georgia’s EU integration. Like Strong Georgia, they advocate for a vetting system to safeguard judicial independence but suggest that further negotiations with the EU may be necessary, especially regarding the involvement of international experts with a decisive role in the vetting process.

To accelerate the process of opening EU membership negotiations and securing final membership, the For Georgia party (led by the GD’s former Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia) plans to implement a series of democratic reforms outlined in their program called Fair Order for Georgia. These reforms focus on critical areas such as judicial reform, human rights protection, anti-corruption efforts, and electoral reforms. The main objective is to end one-party rule and establish a consensus-based democracy that can withstand political changes and ensure long-term governance stability. A vital aspect of this vision is the appointment of key public officials through a consensus among political parties, which the party considers essential for democracy.

Regarding the EU's nine recommendations, For Georgia believes they need to be tackled holistically, aligned with the Copenhagen Criteria and the spirit of the recommendations, and not treated in a fragmented manner. For Giorgi Gakharia, comprehensive institutional reforms must address all recommendations simultaneously. Gakharia’s party also insists that specific EU recommendations need more clarity and better alignment with Georgia's context. For example, the scope, adequacy, and effectiveness of the vetting process for ensuring judicial independence must be thoroughly considered before being implemented hastily.

The For Georgia party acknowledges that the most challenging reform will be the judicial system due to its complexity and historical context. Their vision of judicial reform extends beyond just the courts to the prosecution, law enforcement, and criminal justice policies. Consensus among all stakeholders, both local and international, is essential to recognizing that past reforms have not met expectations. Only after this consensus is achieved can reforms be effectively directed.

In summary, all major opposition parties use European integration as a primary talking point when contrasting themselves and their programs with that of the GD. However, while the UNM is the most vocal in its campaign, all parties share that the nine EU conditions must be implemented swiftly after the change of government to ensure timely opening of EU accession negotiations.

Forgotten NATO

Georgia’s NATO accession has largely faded from the political agenda and is rarely discussed in party platforms or debates. This can be attributed to Georgia’s decreasing prominence on NATO’s radar.

Georgia’s NATO accession has largely faded from the political agenda and is rarely discussed in party platforms or debates. This can be attributed to Georgia’s decreasing prominence on NATO’s radar. As we have consistently discussed on the pages of this journal, the Georgian Dream has all but abandoned the NATO path.

Renewed enthusiasm for EU enlargement, notably after receiving the candidate status in December 2023, overshadows the NATO debate. The recent NATO Washington Summit only mentioned Georgia once alongside Moldova (not aspiring to join the Alliance) in the context of urging Russia to withdraw its forces from both countries.

For the Georgian Dream, NATO membership is not a pre-election talking point. This is understandable since GD political leaders have consistently argued that Russia invaded Ukraine because of NATO’s enlargement attempts. Since the prevention of war, as it happened in Ukraine, is a significant talking point for the GD, accentuating NATO accession makes no sense.

Opposition parties do not talk about the NATO prospects either, mainly not to move the discussion to the GD’s turf – war vs. peace. However, when analyzing their pre-election platforms, one can conclude that the opposition political parties seem divided over whether Georgia should invest diplomatic efforts in pursuing a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) as reaffirmed in the 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit Communique: “We reiterate the decision made at the 2008 Bucharest Summit that Georgia will become a member of the Alliance with MAP as an integral part of the process.”

The Coalition for Change argues that the MAP should be pursued now unless NATO decides to enable Georgia’s membership with other tools. They also argue that signing bilateral security agreements with NATO and EU member states will more directly address Georgia’s security concerns.

Strong Georgia does not talk much about NATO in its public communication. However, the party’s pre-election plan has concrete elements related to Georgia’s NATO accession. For instance, NATO membership and security guarantees are mentioned as a priority. Building a national security system and army according to NATO standards and “synchronizing” Georgia’s defense policy with NATO is considered important. Strong Georgia also advocates for building a “civil preparedness” system according to NATO standards in order to ensure public resilience and more capacity to deal with crises.

For Georgia argues that Georgia could join NATO without a Membership Action Plan (MAP), similar to Sweden and Finland, as NATO has previously stated that Georgia possesses all the necessary practical mechanisms for membership. In addition to NATO, For Georgia also suggests exploring bilateral and multilateral security agreements with individual countries, referencing examples such as US-Israel cooperation and Ukraine’s security agreements with other nations. However, they underscore that while such formats may enhance security, they cannot replace NATO’s collective defense guarantees, which remain Georgia’s ultimate security goal.

As mentioned above, UNM did not provide detailed answers regarding its policy on NATO membership; however, if we refer to its public track record on NATO-Georgia relations and various statements, it can be concluded that it is ardently in favor of pursuing NATO integration policy.

American Factor

Relations with the USA are also at the forefront of the election campaign for all parties. Even though the European integration message trumps the message about Georgia-American relations, the recent imposition of sanctions on Georgian high officials, discussions in the Senate and House on Georgia-related resolutions, and public hearings in the US Congress on Georgian democracy-related issues spiraled the topic of the US-Georgia relations to the center of political discussions on several occasions during the last few months.

For the Georgian Dream, relations with the United States must be revamped. The imposition of sanctions on Georgian high officials and the leak of news to Voice of America about looming sanctions on Bidzina Ivanishvili made the Georgian Dream’s rhetoric even harsher. They blamed the US for blackmailing the party leader, Bidzina Ivanishvili, and intervening in domestic politics and elections.

“The Biden administration rescinded Prime Minister Kobakhidze's invitation to its annual UNGA reception and declined to meet with the Georgian delegation due to increasing concerns about the Georgian government’s anti-democratic actions, disinformation, and negative rhetoric about the United States and the West.”

According to GD leaders, US-Georgia relations will be restarted within a year after the elections. In recent statements, following the uninviting of Prime Minister Kobakhidze from Joe Biden’s UN reception, Georgian Dream leaders were furious. According to the clarification of the US Embassy in Georgia, “the Biden administration rescinded Prime Minister Kobakhidze's invitation to its annual UNGA reception and declined to meet with the Georgian delegation due to increasing concerns about the Georgian government’s anti-democratic actions, disinformation, and negative rhetoric about the United States and the West.”

The government's propaganda narrative pushes two parallel messages to fend off the increasing criticism that GD is responsible for the deterioration of US-Georgia relations. According to the first one, it is the global war party that wants the GD ostracized if Ivanishvili does not agree to open the second front against Russia in Ukraine.

GD’s close alignment with Russia, reverence towards China, and hanging out with the Iranian and Hezbollah/Hamas leaders in Tehran are highly unlikely to draw positive attention from the Trump team or personally the ex-president.

According to the second narrative, the current democratic party administration of the US and the US ambassador to Georgia are the main culprits, which will change as soon as Donald Trump reenters the White House. However, the GD has not yet shown that it has political traction with the Trump team. During a visit to Washington, the Prime minister did not meet with Trump, or his team, despite attempting so, according to various media reports. In fact, the GD’s close alignment with Russia, reverence towards China, and hanging out with the Iranian and Hezbollah/Hamas leaders in Tehran are highly unlikely to draw positive attention from the Trump team or personally the ex-president. Not to mention that the Georgia-related bills in the Senate and House are bi-partisan and are also supported by Trumpist senators and congressmen.

In contrast to the Georgian Dream, the opposition political centers push for strengthening ties with the USA. Inspired and backed by the draft Megobari Act and the Georgian People's Act, which envisages visa liberalization and a free trade agreement with Georgia, the opposition parties argue that when the Georgian Dream leaves power, the promised carrots will materialize. Almost all opposition parties promise to create visa-free travel and sign a free trade agreement with the USA. These are reflected in pre-election promises made by political centers Coalition for Change, Strong Georgia, and the Unity - National Movement.

Opposition political parties, however, do not provide further details on how Georgia can achieve visa-related benefits from Washington. In theory, Georgia can join the US Visa Waiver Program (VWP), which is eligible only for 41 country nationals worldwide, even excluding three EU members (Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Romania). The VWP is granted to the states based on essential criteria that entail concrete steps, such as having a non-immigrant (B1 and B2 category) visa refusal rate of less than 3% of the previous year or a lower average percentage over the previous two years. Georgia's track record is not even close to that requirement since in 2023 adjusted refusal rate for B-visas was 49% in 2022 and varied from 42 to 66% during the preceding ten years.

War, Peace, and Russia

The primary propaganda line for the Georgian Dream is that Georgia will have peace only if it stays in power with the constitutional majority.

The last but not least, the pre-election campaign is heavily centered around Georgian-Russian relations and deoccupation. The primary propaganda line for the Georgian Dream is that Georgia will have peace only if it stays in power with the constitutional majority. This line is reinforced over and over as elections draw closer. In Gori, on 16 September, GD leader Bidzina Ivanishvili vowed to punish the previous government for starting the war in 2008 and promised to apologize for it. In late September, the GD intensified the campaign through street billboards and social media ads, contrasting bombed Ukrainian cities with peaceful Georgian ones. Both of these campaigns caused indignation among the public, but, as the saying goes, there is no bad PR in politics.

Most opposition parties try to exploit on such campaigns by the GD, hoping the controversial statements and steps will damage the GD. According to recent Edison Research polls, 85% of the population did not agree with Ivanishvili’s apology vow. Opposition parties eagerly attack GD for complacency with Russia, for the detour of the foreign policy, and for blaming Georgia for starting the war. Very often, Russian official statements condoning the GD’s message and praising the Georgian government are used to showcase the GD’s pro-Russian stance.

At the same time, almost all opposition parties avoid providing their vision for the deoccupation, conflict resolution, and relations with Russia. This reservation is understandable since, for the opposition parties, the elections are a referendum on Russia vs. EU, not war vs. peace (as the GD wants to portray it).

However, a close look at the political parties’ programs reveals some interesting aspects of the opposition parties’ visions, even if they are very similar. All opposition parties strive for peaceful conflict resolution and reject using force to restore territorial integrity. They also firmly believe that the benefits of European integration and related benefits to the people residing in occupied territories as a primary way of solving conflicts.

When asked whether there should be a direct dialogue with Sokhumi and Tskhinvali, no opposition party rejected the idea; however, all of them stressed the importance of separating the de-occupation process, which concerns Russia’s withdrawal from the occupied region, from the dialogue on humanitarian and human rights-related issues which could take place with the authorities of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. All opposition parties are in favor of spending more money from the state budget for the benefits of the residents of the occupied regions. They also welcome the idea of allowing more engagement of the European Union and the West in general, to ensure that the malign influence of Russia is balanced in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Deeds and Words

An analysis of the foreign policy sections in the pre-election programs and debates from the ruling and opposition parties.

First, these programs are heavily influenced by PR strategies and communication experts, with the primary audience seemingly being political opponents rather than voters. Political parties avoid making detailed promises, keeping their programs vague to avert accountability and prevent their rivals from exploiting their positions for propaganda. The leading information battlefield is about whether the October 2024 elections is about the “EU vs Russia” or “war vs. peace.” There seems to be a tacit understanding that whichever “referendum question” prevails will be a winner. There is some truth in this positioning.

Second, the opposition parties are strongly pro-European. At the same time, they view the EU integration process as a tool to defeat the Georgian Dream, focusing their rhetoric less on shared European values and more on potential financial benefits from Western integration. Opposition parties appear to believe that simply changing the government will prompt the EU to open accession talks, overlooking that Georgia still needs to meet the EU’s nine key reforms proposed in December 2023. All opposition parties support the Georgian Charter which is a consensual document on the implementation of the EU’s nine steps. However, when the time comes, there will inevitably be disagreements on major reforms, whether judiciary or de-oligarchization. The Georgian Charter seems to be the lowest common denominator, sufficient for pre-election purposes but not so much for the concrete reform plan.

Third, NATO accession has all but disappeared from the party narratives. This is not to suggest, however, that NATO accession will not be a priority if a new ruling coalition emerges after the elections. Simply, in the pre-election period, any narrative that feeds the Georgian Dream’s “war vs. peace” propaganda is deemed as not useful.

And fourth, the discourse makes it clear that the elections will determine Georgia’s foreign policy trajectory. The choice between Western integration and isolation and more pro-Russian policies is as stark as it gets. When the election results are known on 26 October, provided that the elections are free and fair, the world will know whether the Georgians have chosen the pro-Western opposition parties with strong pro-EU and pro-American positions or a Georgian Dream, whose pre-election rhetoric has been heavily dominated by anti-Western statements, which often coincide and are endorsed by Moscow.

But more importantly, the October 2024 elections will be a test whether it is indeed the economy or foreign policy that determines the outcome of the Georgian elections.