WHAT IS NEXT FOR GEORGIA? SCENARIOS FOR THE UNFOLDING CRISIS - Joint Article

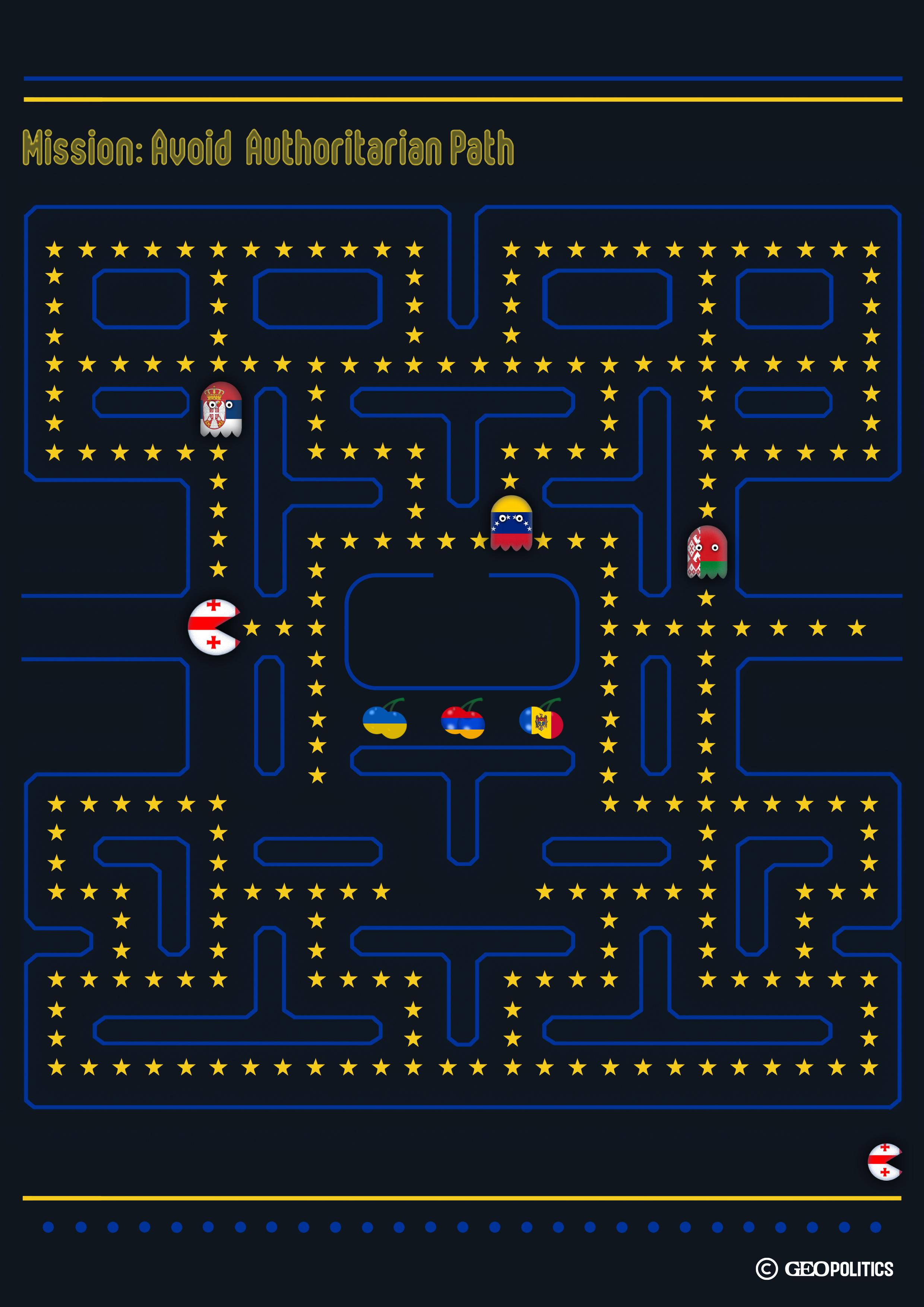

What is going to happen in Georgia? Will the events unfold like in Belarus? Or like in Armenia? How about Venezuela or Serbia? These have been some of the frequently asked questions since November 2024, when the Georgian Dream (GD) decided to formally reverse the country’s long-standing European integration path, sparking almost non-stop protests throughout the country.

Since November 2024, Rustaveli Avenue has been closed every evening along with large-scale protests on New Year's Eve, general strikes, marches of different social groups, and daily demonstrations at the public broadcaster, demanding that the people's voice be heard on state TV. Public broadcaster is now as much a part of Ivanishvili’s power structure as the law enforcement agencies and the judiciary. This daily effort and perseverance distinguish current protests from any other in Georgia's history.

In the past week, self-organized protest groups decided to hold a demonstration at the entrance to the capital, which, if it led to a mass gathering, would block the road. In response, on Friday, 31 January, a new government decree was issued, designating roads as part of a list of strategic infrastructure sites, thereby criminalizing their closure. Despite numerous threats and attempts at intimidation from both Georgian Dream leaders and law enforcement agencies, the protesters gathered again on 2 February, which led to renewed violence, including brutal beatings and arrests. Since November of the previous year, over 500 people have been imprisoned with more than 40 facing criminal accusations. Among those arrested were the Coalition for Change leaders, including Nika Gvaramia, Zurab Japaridze, Nika Melia, Elene Khoshtaria, and other politician figures. Additionally, former Georgian Dream Interior Minister and Prime Minister, now leader of the For Georgia party, Giorgi Gakharia, was physically attacked by the Georgian Dream member of Parliament.

Prominent cases of detained persons include Mzia Amaghlobeli, the founder of the Georgian online media outlets, Batumelebi and Netgazeti, who has been on a hunger strike since her arrest on 12 January. Alongside her, Georgian actor Andro Chichinadze has also become a symbol of this struggle. In his support, the Vaso Abashidze New Theatre created a manifesto calling for the release of all political prisoners. The theatre has begun a nationwide tour, performing in various cities and regions across Georgia, engaging with audiences and raising awareness about the ongoing political crisis. Notably, “Fire to the Oligarchy” has become an unofficial motto of the protests.

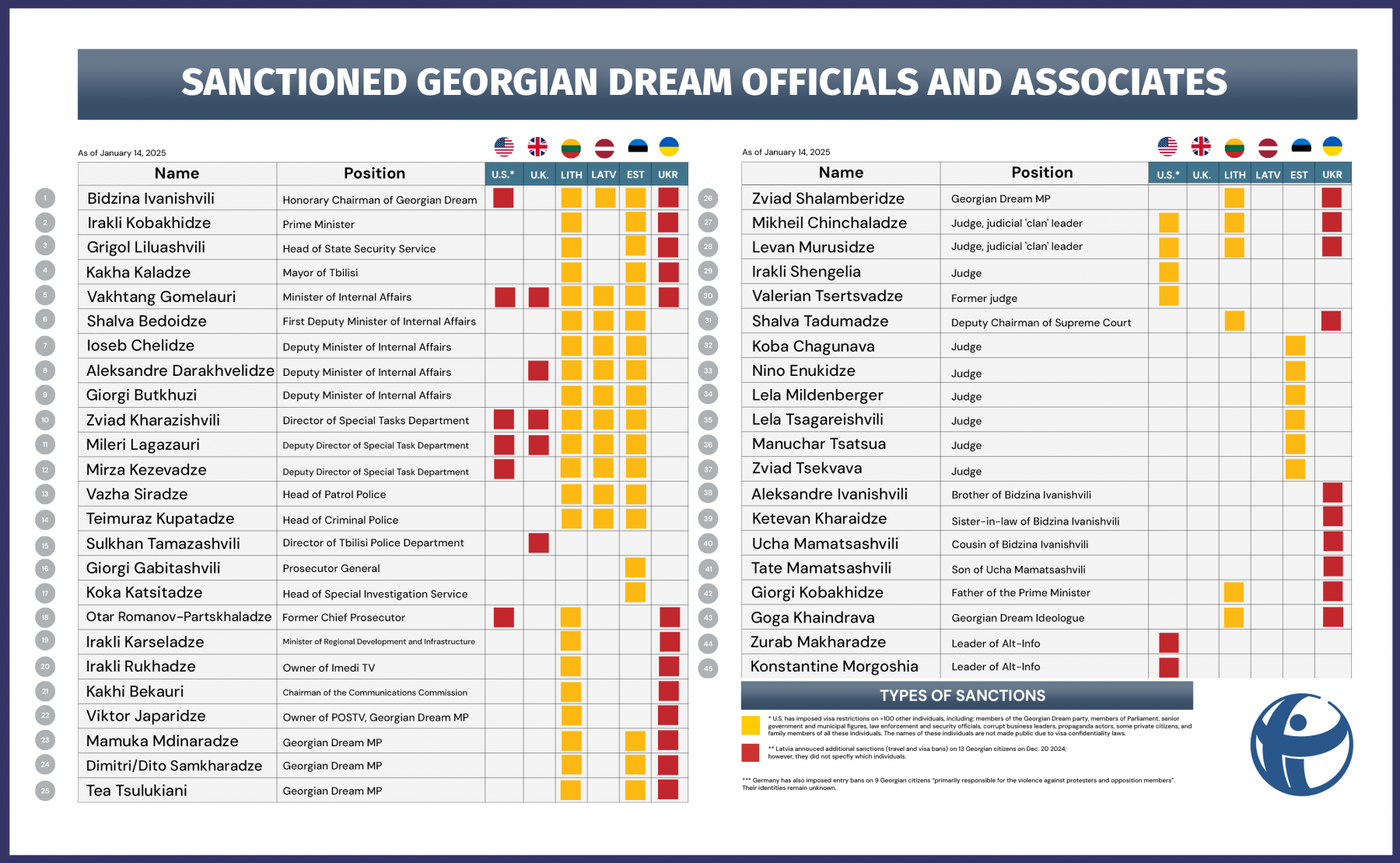

The Georgian Dream’s repressions have plunged Georgia into international isolation. Western capitals have condemned the government’s actions, and while sanctions against individuals in the ruling elite have become widespread, discussions are underway for more punitive measures. As a result, Georgia’s foreign policy and security have become minimalistic, leaving the country wondering in the void of changing international politics, which we discuss in detail elsewhere in this issue. The collateral damage of this crisis is the welfare and security of Georgians who are now facing growing economic, financial, and political turmoil. Considering all these factors, the naïve but honest question about what comes next and whether or not Georgian events are comparable with those of other protest movements deserves merit.

While we cannot predict the future, we can analyze possible scenarios. The crisis might explode or implode, depending on how the events unfold. The contributors to this journal put their heads together to examine various scenarios and their probabilities in a situation in which the Georgian Dream remains intransigent and the protest movement—through resilience—has yet to force a breakthrough. Roughly, there are three scenarios. The Georgian Dream prevails in one, and its rule becomes fully authoritarian. Sub-scenarios will only differ regarding the legitimacy of the regime, its fragility, and resources to deal with the economic challenges. In the second scenario, new elections are called, or the change of power happens due to the peaceful protests and the high pressure. In the third one, the crisis lingers on, leaving all possible options open. Each of these crises resembles similar processes in other countries around the globe in the recent decade but also has striking differences from each of them.

Serbian Scenario: Authoritarianism Under the EU Shadow

Many have compared the events in Georgia with those in Serbia during the last decade. For years, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has maintained an authoritarian system while keeping the European Union engaged. Resistance from the opposition, public protests, elections (often snap ones), and student rallies have not resulted in a change of power. In this, Georgia and Serbia resemble each other.

The events since November 2024 also share many similarities. Massive anti-corruption student protests in Belgrade and hundreds of other towns, cities, and villages resemble the Georgian protest dynamic. Georgians even attempted to block a highway, similar to Serbian students in January 2025.

For decades, Aleksandar Vučić’s government has promoted conspiracy theories, branded civil society as spies on foreign pay, and increasingly channeled traditional religious conservatism. The “Vučić system” is based on three pillars: a party-based patronage network, dominant security services, and unfettered propaganda. Leveraging economic ties for political benefit and balancing the interests of the EU, China, and Russia in politics and economy has become a hallmark of Serbia’s foreign policy.

The Georgian Dream has already installed a political system fairly similar to that of Vučić.

In this sense, the Georgian Dream has already installed a political system fairly similar to that of Vučić. The missing element is the degree to which Belgrade managed to ingratiate itself with Brussels despite these shortfalls.

The Serbian scenario seemed to be the natural direction the Georgian Dream regime took before the 26 October parliamentary polls. However, the 28 November announcement of breaking membership talks with Brussels and open hostility toward the European Union set Tbilisi off that track.

To revert to the Serbian scenario, the Georgian Dream government would need to take several steps:

First, it will need to appoint a Prime Minister with a more conciliatory attitude towards Brussels and change the tone from hostile to skeptical. Anna Brnabić served that purpose in Serbia from 2017 to 2024. This, however, does not seem likely. Not because Kobakhidze cannot be disposed of – an oligarch can eliminate any pawn from his chessboard. However, to become conciliatory with Brussels, the whole propaganda machinery has to be revamped, the message box changed, and the party line distorted. That does not seem likely or feasible at this point.

Second, the Georgian Dream needs to acquire tangible economic leverage on Brussels, something which is impossible. The GD tried to advance the idea of the trans-Black Sea power cable with assent from both Baku and Budapest, but the talk of that initiative has died down, and its value does not trump the value of democracy in the country. To get Brussels’ interest back, the Georgian Dream needs the economy to be on its side. For Serbia, a prospective lithium mine is one such leverage that Brussels cannot ignore. Moreover, Serbia is an economic powerhouse of the Balkans. Georgia is not.

Third, Georgia needs to become a part of a regional geopolitical solution, not a problem. Vučić’s key success has been to transform Belgrade’s role into a regional power-broker and EU partner, not a spoiler, in relation to, for example, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This allowed Belgrade to be more exigent on Kosovo. In contrast, Georgia has placed itself firmly in the shadow of Russia, countering Western interests in the region, helping Moscow to sidestep sanctions, and embracing its anti-Western narratives.

Sacking public servants, getting rid of the Parliamentary Research Center, cutting the Civil Service Bureau, and removing NGOs from the consultation boards of civil service contradicts the Serbian way.

Fourth, the Georgian Dream needs to make public administration compatible with that of the EU. With all of its anti-democratic drift, Vučić consolidated Serbian public administration and became an efficient partner of the EU bureaucracy. Georgia had a good track record of this and the potential of doing the same; however, the Georgian Dream’s recent dismantlement of the independent civil service delivered a severe blow to this element. Sacking public servants, getting rid of the Parliamentary Research Center, cutting the Civil Service Bureau, and removing NGOs from the consultation boards of civil service contradicts the Serbian way.

Fifth, the Georgian Dream will have to remove all of the suppressive laws that it has adopted since spring 2024, including the laws on foreign agents, LGBT propaganda, and a series of legislative changes criminalizing or fining protests from various perspectives. Ivanishvili seems to be on a completely different track. In fact, on 5 February, his team announced further changes, targeting media and civil society, cracking down on drug use, and tightening immigration legislation.

The Serbian scenario may be the best way out for the Georgian Dream. This way, they would maintain autocracy and good relations with the EU at the same time. But because of how far Ivanishvili has gone in centralizing power and squashing democracy, this scenario seems to have a low probability at the moment.

Belarus Scenario: Forced Repressions and Complete International Isolation

Under this scenario, the Georgian Dream fully embraces authoritarian rule, suppressing dissent through mass arrests, intimidation, and violence. The state’s repressive apparatus would be used to eradicate opposition voices, much like Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in Belarus. The civil service and academia will be cleansed, the businesses that support the opposition will be seized or silenced, and critical education institutions will be shut down, or their revenues will be cut. The protesters will be detained, kicked out of the country, or allowed to flee.

The Georgian Dream has now created an investigative commission in the Parliament which will likely be used to demonize the United National Movement and other opposition parties and uncover the “crimes” they have committed, including during the 2008 Russia-Georgia war. This process will likely lead to banning the political parties and arresting their leaders, including those who ignore the subpoenas by the investigative commission – a criminal offense by Georgian law. Lukashenko has already achieved this – most opposition leaders are behind bars or out of the country. And this is “their choice” as he famously quipped back at a BBC journalist in January.

Signs of the Belarus scenario are already visible: the Georgian Dream has already detained over 500 protesters (arrests still continue) and leaked reports indicate that a list of 150 individuals—including journalists, activists, and opposition leaders—is being prepared for their arrest. The squadron of special police is as violent as the Belarusian special forces, and the survival of the regime in both cases depends on brute force.

Similar to Belarus, the protesters in Georgia are mainly from the middle class and the youth, which means that they have not only a lot to lose but also other alternatives in life, including sources of income.

Similar to Belarus, the protesters in Georgia are mainly from the middle class and the youth, which means that they have not only a lot to lose but also other alternatives in life, including sources of income. This means that if the crackdown continues, intensifies, and the regime shows no signs of backing off, many protesters might leave the country (visa-free with the EU is helpful here) or stop protesting to be able to sustain their families.

If this scenario materializes, Georgia’s international isolation will become a fait accompli. Lukashenko is already used to this and Ivanishvili is getting used to having no allies in the West. The rhetoric and actions of the Georgian Dream, including the recent withdrawal from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe after being given temporary conditional credentials, show that detaching from international institutions is not a problem for Ivanishvili. It might be a problem for some in his team but those who are not making the decisions have no say in the strategy.

At the same time, Georgia lacks some critical elements that enabled Belarus to sustain such an isolationist, inward-looking authoritarian system:

Security Forces’ Capacity: Lukashenko has complete control over the military and security forces while the Georgian Dream faces internal divisions and doubts within law enforcement ranks. The patrol police are not happy with the brutal crackdowns of the special forces. If the decision is made to become even more ruthless, upscaling to killing its citizens, it is not guaranteed that the historically obedient law enforcement will comply. Georgia, unlike Belarus, is quite a small country and families are already divided by politics. If the division becomes more profound, it might backfire on the Georgian Dream.

The Georgian Dream, by contrast, does not have guaranteed Russian security assistance and Russian presence on the ground. Indeed, this might change quickly if Russia decides to intervene openly and support Ivanishvili.

Russian Backing: Belarus survived intense international pressure and domestic uprising thanks to Moscow’s unwavering support, including financial, military, and political. The Georgian Dream, by contrast, does not have guaranteed Russian security assistance and Russian presence on the ground. Indeed, this might change quickly if Russia decides to intervene openly and support Ivanishvili. However, direct Russian intervention will come with a higher domestic political cost. The Georgian Dream’s propaganda is all about preventing Russia from attacking Georgia while continuing with the European integration efforts. If they invite the Russian military, the popular discontent will likely rise, something which could become a tipping point for Ivanishvili’s clinging to power.

Legitimacy Crisis: Unlike Belarus, where Lukashenko has ruled for decades, the Georgian Dream’s mandate is much weaker. In Belarus, generations have seen or known no other ruler but Batska. In Georgia, the Georgian Dream has only been in power for 12 years and supporters of the previous administration are abundant. The opposition has been receiving 30-40% of votes in every election since 2014 and despite being fragmented and leaderless, the Georgian Dream has never managed to surpass 60% support, even with the loyal Central Election Commission and electoral fraud.

A Belarus scenario would probably suit Ivanishvili and his team. If events develop in a Belarusian way, Georgian Dream leaders will become fully immune to Western pressure and consolidate power. Therefore, if the protests are squashed, the probability of this scenario will be moderately likely.

Venezuela Scenario: a Crisis that Never Fully Ends

In a Venezuelan-style scenario, much like in Belarus, the Georgian Dream consolidates full authoritarian control. However, unlike Belarus, this comes with the added challenge of economic instability and a volatile domestic situation, making long-term regime survival far more uncertain.

Venezuela has become synonymous with authoritarianism, economic collapse, and political repression. As Georgia faces its longest-running protests and deepening political crises, comparisons are beginning to look legitimate. In both cases, democratic backsliding has fueled mass resistance.

Over the past decade, Venezuela has become synonymous with authoritarianism, economic collapse, and political repression. As Georgia faces its longest-running protests and deepening political crises, comparisons are beginning to look legitimate. In both cases, democratic backsliding has fueled mass resistance. In Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro systematically dismantled democratic institutions, undermined elections, and repressed opposition leaders, ensuring that power remained in his hands. The state became a tool for consolidating his rule, with courts, electoral commissions, and military and security forces bending to his will. Georgia has a similar trend. The Georgian Dream has steadily captured key institutions, weakened the judiciary, and used law enforcement against protesters and civil society activists. The Georgian opposition, however, is still legally active, but the government increasingly relies on legal maneuvers and disinformation to discredit its critics, echoing some of the tactics used in Venezuela. Once Ivanishvili moves to outlaw the opposition and close the media, the only remaining difference will be the economy.

Public resistance in both countries has taken the form of long-running, large-scale protests, though their origins and outcomes differ. Venezuelans took to the streets repeatedly—first in 2014, again in 2017, and then in 2019 and 2024—demanding Maduro’s resignation, free elections, and an end to economic mismanagement. But each wave of demonstrations was met with violent crackdowns, mass arrests, and the militarization of security forces. This scenario is likely in Georgia, too. If the 2024-25 protests are squashed, new protests might reappear, leading to continuous crisis and instability.

Another difference from Venezuela is the role of the military. As we have explained in the previous issue of GEOpolitics, the military in Georgia has remained neutral and the police—while used for political repression—have not yet reached the level of systemic brutality seen in Caracas. But this, too, can be easily changed, depending on how the situation evolves.

One significant difference from the Venezuela scenario is the economy. Venezuela’s collapse was driven by years of corruption, hyperinflation, and failed socialist policies, exacerbated by international sanctions. Millions fled the country, seeking refuge in neighboring nations as food shortages and economic despair took hold. Georgia, by contrast, has maintained relative economic stability, although concerns are growing about the economic downfall, dwindling remittances, foreign investment risks, and potential financial isolation if the country continues to drift away from the West. While there is no immediate threat of hyperinflation or mass migration, a prolonged estrangement from the EU could weaken Georgia’s financial standing and push it further into dependence on Russia and China—just as Venezuela became reliant on Russian and Chinese aid to survive. In Venezuela, oil revenues were enough to sustain the regime and enrich the rulers at the expense of the people. In Georgia, there is no such source of revenue. Yes, Ivanishvili is a billionaire, but if the country plunges into the recession and protests acquire social character, it will be very hard to sustain the regime financially and counter the poor simultaneously.

Perhaps the starkest difference between the two countries lies in how power is contested. In Venezuela, the opposition, led at various points by figures like Juan Guaidó, Maria Machado, or Leopoldo López, attempted to mount a coordinated resistance to Maduro’s rule, only to be systematically dismantled by the regime’s repression. In Georgia, the protest movement lacks a single leader. Rather than being driven by opposition political parties, it is essentially a grassroots, civil society-led effort. This decentralized nature makes it harder for the government to target individual leaders. Still, it also means the movement lacks a clear political strategy for translating street protests into lasting political change.

The trajectory of both countries also hinges on their geopolitical positioning. Venezuela became a battleground for competing global powers with the United States and the EU backing the opposition while Russia, China, and Iran propped up Maduro’s government. Georgia, too, finds itself at a geopolitical crossroads, but its situation is not yet as dire. While the Georgian Dream has increasingly pursued a Russia-friendly course, the West has not fully abandoned the country and its people. However, if Georgia’s EU aspirations are permanently derailed and repression continues to escalate, Western disengagement could accelerate, leaving Georgia vulnerable to more profound Russian influence—just as Venezuela fell into Moscow’s orbit.

Georgia is not Venezuela—but the coming months will determine how closely it comes to following a similar path.

For now, Georgia is not Venezuela—but the coming months will determine how closely it comes to following a similar path. This scenario, basically a win of authoritarianism, but with a fragile economy and severe instability, is also moderately likely, granted that the Georgian Dream breaks the will of the protesters.

Armenian Scenario: Successful Protest With a Leader

Amid recent developments in Georgia, some even draw parallels with Armenia’s 2018 protests that brought Nikol Pashinyan to power. Indeed, the Georgian and the Armenian protests share some fundamental characteristics. In both cases, the protests involved mass participation from capital cities and regional areas. In both cases, the support from the diaspora was crucial and overwhelming. The Georgian Dream lost the foreign-based electoral precincts, garnering only 15% of the vote. The protests in both countries mobilized diverse social groups and became nationwide. In both cases, the demonstrations were political rather than purely social and concerned the country’s future trajectory.

However, the differences between the Armenian and the Georgian events are far more pronounced, making this scenario less likely to be replicated in Georgia.

The trigger for mass protests in Armenia in 2018 was then President Serzh Sargsyan’s decision to extend his rule by becoming Prime Minister after a decade in power. In contrast, the protests in Georgia were not sparked by the rigged general election of 26 October 2024 but, rather, by the 28 November announcement from Georgian Dream Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze declaring that the country’s EU accession process would be postponed until at least 2028. This announcement became a crucial test of whether or not the overwhelming popular support for Georgia’s EU integration—sustained for years—was genuine and resilient.

Unlike the Armenian protests, the Georgian movement lacks a prominent leader. It is orchestrated not by opposition political parties but by a diverse coalition of civil society groups.

Another key difference is the duration of the protests. In Armenia, the protests lasted around 40 days, were on the rise, and culminated with the change of power; in Georgia, more than 70 days have passed. While the demonstrations continue with no signs of abating, they come with ebbs and flows. Culmination has not occurred yet and is hard to foresee any time soon.

Most importantly, unlike the Armenian protests, the Georgian movement lacks a prominent leader. It is orchestrated not by opposition political parties but by a diverse coalition of civil society groups.

Instead of engaging with the protesters, the ruling party has either ignored or sought to discredit them, branding demonstrators as “people without a homeland” and accusing them of being part of the so-called “Global War Party” and “Deep State,” implying a conspiracy orchestrated by the West.

Furthermore, the government’s response diverges significantly. After 40 days of mass protests in Armenia, Sargsyan stepped down, acknowledging his mistake, and the Parliament elected Pashinyan as the Prime Minister. In contrast, the Georgian Dream has shown no willingness to compromise. Parliament is considered illegitimate, and as of 7 February, all opposition MPs have been stripped of their mandates, bringing down the number of MPs to 101 (from 150). Instead of engaging with the protesters, the ruling party has either ignored or sought to discredit them, branding demonstrators as “people without a homeland” and accusing them of being part of the so-called “Global War Party” and “Deep State,” implying a conspiracy orchestrated by the West.

In the Armenian scenario, the opposition and civil society defeated the incumbent. In Georgia, the success of the protest movement, if it happens, will likely take a different course than in Armenia. The differences are too stark; therefore, the leader-led transition is improbable.

Ukraine Scenario: Euromaidan/Eurolution?

As Georgia’s political crisis deepens, comparisons with Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution of 2013-2014 are inevitable. Both movements were driven by a fundamental choice between a European future and increasing alignment with Russia. Both saw governments resisting public demand for EU integration. In both cases, mass protests turned into existential struggles for the country’s political future. However, while the parallels are striking, the differences are even more pronounced, making it unlikely—at least for now—that Georgia’s protests will follow the Ukrainian trajectory. But if Bidzina Ivanishvili makes the same miscalculations as Viktor Yanukovych, the possibility of a full-scale confrontation cannot be excluded.

The most fundamental distinction between Euromaidan and Georgia’s protest movement is the level of organization and resources available to demonstrators.

The most fundamental distinction between Euromaidan and Georgia’s protest movement is the level of organization and resources available to demonstrators. In Ukraine, the protesters were not just an organic grassroots movement; they were also backed by wealthy oligarchs, political opposition figures, and even regional elites who saw an opportunity to break from Yanukovych’s rule. Financial support flowed into Maidan, funding everything from food supplies to medical aid to makeshift defenses. Volunteers coordinated logistics with military-like efficiency, setting up barricades, self-defense units, and even rudimentary governance structures. In contrast, despite their longevity and resilience, the Georgian protests lack such deep-rooted self-organization and financial backing, save for sporadic crowdfunding of protest activities, the government imposed hefty fines and assistance to the detained demonstrators. What sustains the Georgian protests is a deep-seated public frustration with the Georgian Dream’s policies, but not the well-structured resistance that defined Euromaidan.

Another critical difference is that Georgian security forces are vastly more prepared than Ukraine’s were in 2014. The infamous Berkut riot police, who attempted to suppress the Euromaidan protests, were poorly coordinated, underfunded, and riddled with internal divisions. When violence escalated, they struggled to maintain control, ultimately resorting to deadly but chaotic force. In Georgia, however, the security apparatus is far more sophisticated. The Georgian Dream’s security services—GDD and affiliated law enforcement agencies—are well-trained, well-equipped, and far more disciplined than Berkut ever was.

This is where the true risk of escalation lies. Unlike Ukraine, where state weakness allowed a mass uprising to overpower the government, Georgia’s security forces are in a position of strength. However, history has shown that regimes often miscalculate their own control over events. In Ukraine, everything changed when Yanukovych ordered his forces to fire on demonstrators, leading to dozens of deaths. This act of state violence became the tipping point, radicalizing even moderate protesters and ensuring that Yanukovych’s rule was no longer tenable. If Ivanishvili were to make the same mistake—if his government resorts to lethal force against civilians—then all current assumptions about the trajectory of Georgia’s crisis could be shattered.

That said, there is another key difference that makes a Ukrainian-style escalation less likely: Georgia’s political culture has changed since its violent past. In the 1990s, Georgia was a country where political disputes were often settled with bullets rather than ballots, but that era is long gone. The idea of taking up arms is no longer embedded in the political mindset of most Georgians. Unlike Ukrainians in 2014, who had a recent history of armed conflict and an already active paramilitary presence in the east, Georgians do not have the same inclination toward violent resistance. Even if Ivanishvili’s government were to intensify repression, it is unlikely that protesters would take up weapons in response. Instead, the more probable outcome would be a mass political awakening rather than an armed insurgency.

Another significant difference between Georgia’s crisis and Ukraine’s Euromaidan is the scale and sophistication of government propaganda. While Viktor Yanukovych did control state media and tried to discredit the Maidan protests, his propaganda machine was basic as compared to what the Georgian Dream has built over the years. Yanukovych’s messaging was often awkward and unpersuasive, relying on outdated Soviet-era narratives and lacking the systematic coordination seen in modern information warfare.

The Georgian Dream operates a highly sophisticated and coordinated propaganda ecosystem, spanning state-controlled media, pro-government TV stations, online disinformation networks, and social media manipulation.

In contrast, the Georgian Dream operates a highly sophisticated and coordinated propaganda ecosystem, spanning state-controlled media, pro-government TV stations, online disinformation networks, and social media manipulation. The ruling party has weaponized smear campaigns, conspiracy theories, and psychological operations to an extent that Yanukovych’s administration never achieved. Protesters are painted as “foreign agents,” “Western puppets,” and “traitors to the homeland,” and government-affiliated media work tirelessly to delegitimize the movement. The scale of this propaganda is aimed at domestic audiences and international observers, seeking to frame the protests as a radical, foreign-backed destabilization campaign rather than a genuine expression of public discontent.

Ultimately, while Georgia’s crisis may echo Euromaidan in its fundamental political stakes, the structural differences in organization, resources, security forces, and political culture make a direct replication unlikely. However, the lesson from Ukraine remains clear: a government’s miscalculation in repressing dissent can turn an unresolved political struggle into an irreversible confrontation. If the Georgian Dream crosses that line, the current movement could transform into something far more consequential than even Ivanishvili anticipates. The key question is whether or not he will realize the limits of his power before it is too late—or if he will follow in Yanukovych’s footsteps and gamble his regime on the use of force. The probability of this scenario is, therefore, impossible to assess without factoring in an unknown variable – Ivanishvili’s decision to shoot at his people.

Which One?

We are unable to provide a precise answer to this question. However, the Georgian Dream will likely escalate repression, but full Belarus-style authoritarianism may be beyond its capabilities. Economic deterioration and international pressure could force some tactical concessions but not enough to resolve the crisis entirely. Unless a unifying leader emerges or external forces dramatically shift the situation, Georgia is poised for prolonged political paralysis and uncertainty.

The situation in Georgia will likely unfold in one of two ways: a protracted crisis or an escalation into violent confrontation. The former appears more probable while the latter, though less likely, remains a dangerous possibility.

In the protracted crisis scenario, the protest movement gradually loses momentum as it struggles to achieve a decisive breakthrough. The absence of centralized political leadership, which initially helped sustain the movement’s broad-based appeal, eventually became a weakness. The Georgian Dream government continues its strategy of targeted repression, focusing on protesters, journalists, and activists, keeping the movement fragmented and unable to generate sustained pressure. While demonstrations continue in various forms—such as street marches, cyber activism, and occasional strikes—their scale diminishes over time, allowing the Georgian Dream to consolidate its power and become fully dictatorial – probably embracing Venezuelan or Belarusian development models.

Simultaneously, government propaganda will escalate, employing smear campaigns, personal attacks, and the widespread application of the Foreign Agents Law to delegitimize civil society and opposition voices. The Georgian Dream will find more room to maneuver as international attention shifts to other global crises. The ruling party will actively seek closer ties with non-Western actors to compensate for its growing isolation from the West. This could include restoring diplomatic relations with Russia, expanding cooperation within the 3+3 format, or even pursuing membership in BRICS—all moves that would reinforce the Georgian Dream’s position among its domestic supporters while strengthening its leverage in future negotiations with the West.

The US is likely to remain distracted by other global priorities. At the same time, the EU and multilateral organizations, such as the OSCE and the Council of Europe (CoE), may choose selective engagement with the Georgian Dream, justifying this as a pragmatic attempt to maintain influence in Georgia rather than pushing it entirely into Russia’s sphere. Under these conditions, the next major test will be the local elections where the opposition will face a difficult decision: either boycott the vote as a form of protest or attempt to compete in key cities to challenge the ruling party’s dominance. In this scenario, President Salome Zourabichvili could emerge as a unifying figure, assuming leadership in the opposition’s efforts to mount a serious challenge to the ruling party.

Whether or not any of these developments occur, one thing will be clear – in this course of events, Bidzina Ivanishvili will have secured an unchallenged grip on power, making Georgia as authoritarian as ever and aligning Georgia’s foreign and security policy with those of Russia and China. The rest will be details that history will not remember.

In contrast, the escalation scenario could be triggered by an unpredictable act of repression, a high-profile arrest, or a symbolic moment that reignites mass outrage. If protests regain intensity, the government may resort to violent suppression using special forces which could provoke retaliation from demonstrators and escalate the standoff into direct confrontation. If tensions spiral out of control, the government may impose a state of emergency to reassert control.

A crisis of this magnitude would place immense pressure on the military, forcing it to either support the government or side with the protesters. The military’s decision would ultimately determine the outcome. Unlike in a prolonged crisis scenario, in an escalation, one side emerges as the clear winner while the other is defeated.

A crucial factor in this scenario is the possibility of Russian involvement. Whether or not Moscow intervenes will depend on the situation at the time. If the war in Ukraine has wound down and a ceasefire is in place, Russia may seize the opportunity to support Bidzina Ivanishvili’s regime, ensuring Georgia remains under its influence. However, if the Ukrainian saga continues and Russia remains overstretched, its ability to intervene might be limited (like it was in Syria). In that case, the Kremlin may prefer to stay out of Georgia’s internal struggle, opting to contain the crisis rather than escalate it into an international conflict.

Although this scenario is less probable than a protracted crisis, it cannot be ruled out entirely. The potential for escalation remains significant, particularly given the Georgian Dream’s determination to cling to power at any cost. While some may argue that escalation could take a non-violent form, recent trends suggest that Ivanishvili’s regime is unwilling to relinquish control, even in the face of overwhelming public resistance. The coming months will reveal if Georgia slides into a prolonged stagnation or the political confrontation reaches a breaking point.

At this stage, one might ask, whether there is really no way for a peaceful and civilized resolution of the current stand-off. Sure there is. For that, the oligarch must decide to drop all non-democratic authoritarian instruments and call for new elections. That, unfortunately, is not going to happen. What could happen though, is for Ivanishvili to be pushed to the corner so that he has no other option, but to dispel the tensions with the new election. That tension can only be sustained if three components are present.

First of all, the number of protesters has to increase and the protests need to become more diverse, intensive and disrupting. This would paralyze the response capacity of the Georgian Dream.

Second, the international pressure on Ivanishvili and his political team, through sanctions, travel bans and diplomatic isolation, needs to tip the scales in favor of the concessions. So far, this is in the making but a lot more can be done, especially by individual EU member states.

And finally, the economic stagnation, or a perception of thereof, will be key in making Ivanishvili to concede. With continuous internal and external pressure, if an economic downturn brings out socially vulnerable and poor, Ivanishvili will have no other choice but to concede.