Georgia’s Near-Frozen Trade Relations with the EU

EU-Georgia relations have reached a historic low just a little over a year after Georgia was granted EU candidate status in December 2023. The EU and its member states have refused to recognize the results of the 2024 parliamentary elections, suspending politically significant EU budgetary and bilateral assistance programs. Additionally, no high-level meetings or cooperation format discussions are currently planned. These measures are a direct response to the Georgian Dream (GD) leadership’s decision to halt Georgia’s EU integration efforts until 2028, the end of their current term.

Amid this unprecedented political tension, EU-Georgia trade and economic relations, governed by the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), are also showing signs of decline. Before analyzing the reasons for this decline, two factors need to be stressed.

First, like any trade agreement, the DCFTA is merely one tool—albeit an important one—for fostering trade growth and diversification. It is not a panacea or a transformative solution for economic development. Its effectiveness is inherently limited if not complemented by a supportive economic environment, a favorable business climate, and robust trade policy measures.

Second, the economic benefits of the DCFTA were always expected to materialize in the medium to long term. Beyond tariff liberalization, the agreement required substantial legal alignment of Georgian trade and economic legislation with EU standards. This legal approximation aimed to lay the groundwork for the sustainable integration of Georgia’s economy into the EU, fostering increased exports and trade turnover over time. However, these changes came with significant regulatory adjustment costs as they necessitated the establishment of new institutions and expanded functions for the state to oversee and regulate market processes effectively.

Ten years have passed since the entry into force of the EU-Georgia DCFTA. By now, the legal approximation process is almost over, but Georgia’s trade with the EU has grown only at a marginal rate.

Ten years have passed since the entry into force of the EU-Georgia DCFTA. By now, the legal approximation process is almost over, but Georgia’s trade with the EU has grown only at a marginal rate. In 2014-2023, Georgia’s exports to the EU grew just by 1% annually, and the EU-Georgia trade turnover grew by a mere 4% on average during the same period. This result is far worse than expected and, paradoxically, dramatically worse than Georgia’s trade performance with the EU before trade liberalization through the DCFTA.

DCFTA was Built on Solid Foundation

In 2005, Georgia proposed the idea of a free trade agreement with the EU, a move primarily driven by the Russian embargo imposed on all Georgian agricultural exports in 2006. In this context, expanding exports to the EU became a crucial strategy for trade diversification while also serving the political objective of deepening ties with the Union, whose membership was something Georgia aspired to. Initially, the EU was hesitant to engage in substantive discussions with Tbilisi. However, following extensive consultations, negotiations began in 2011, and the agreement eventually came into force in 2014.

For the EU the DCFTA was designed to encourage Georgia to align its trade and economic regulations with EU standards. While this alignment came with substantial conditionalities, it also served as a tool of soft power, shaping Georgia’s economic policies and fostering closer integration.

When DCFTA negotiations began in 2011, EU-Georgia trade and Georgia’s exports to the EU were at their peak, increasing by 29% that year. Georgia’s tariff system was highly competitive, with zero tariffs on nearly 85% of goods. Its trade and customs regulations and business environment were internationally recognized as favorable. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business 2014 report, which assessed business regulations in 189 countries, Georgia ranked 8thglobally. Additionally, the Enterprise Survey 2013 by the World Bank found that 85.8% of entrepreneurs did not view corruption as an obstacle to business. Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2013 indicated that only 4% of Georgians had paid a bribe in the past year. Moreover, Georgia ranked 22nd in the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom by the Heritage Foundation.

Before the DCFTA negotiations began, Georgia had already made substantial progress in trade diversification and demonstrated resilience in navigating the Russian trade embargo. By 2011, the EU accounted for 27% of Georgia’s trade, with Türkiye (16%), Azerbaijan (11%), and Ukraine (9%) among its top trading partners. Notably, Germany, Bulgaria, and Italy—three EU member states—were also in Georgia’s top ten trading partners. At the same time, Russia’s share of Georgia’s exports was negligible at just 2%.

This solid foundation provided a promising starting point for Georgia to benefit from the DCFTA. Among other opportunities, it positioned the country to attract trade-related foreign direct investment (FDI) by offering a competitive environment for production and export to the EU. Georgia had the potential to function as a trade and investment hub for the broader region, provided it engaged in targeted FDI promotion to draw investment into value-added production sectors. The combination of an internationally competitive business climate and advantageous trade regimes gave Georgia a unique comparative advantage.

Interestingly, even today, Georgia’s potential to position itself as a regional trade hub and to expand and diversify its economic relations remains theoretically strong.

Interestingly, even today, Georgia’s potential to position itself as a regional trade hub and to expand and diversify its economic relations remains theoretically strong. The necessary preconditions are in place, yet the tangible impact is lacking. Recent discussions about the strategic importance of the Middle Corridor further highlight Georgia’s potential role, but this remains largely unrealized in practice.

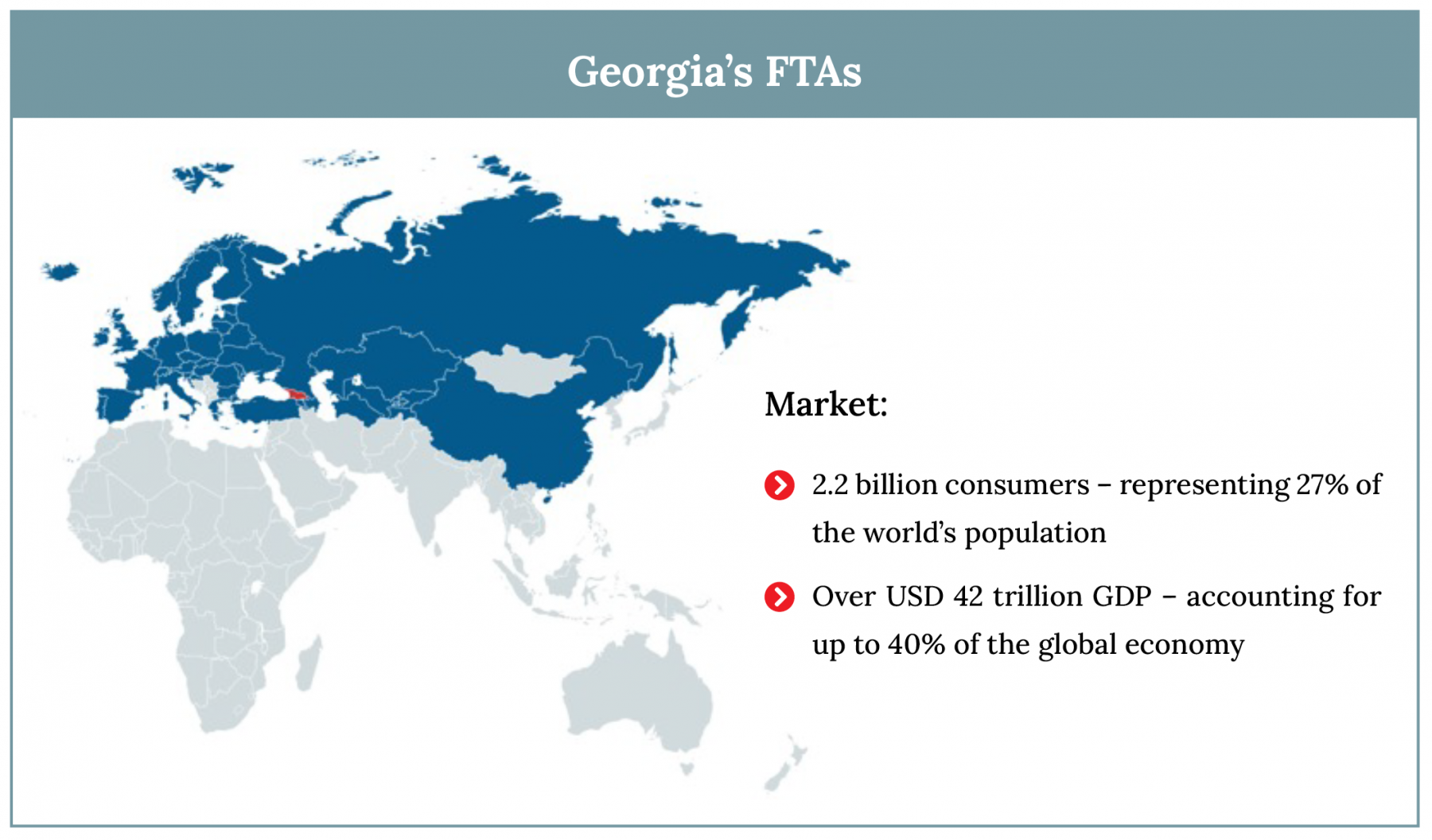

Georgia currently enjoys a free trade regime with markets encompassing 2.2 billion people, representing 27% of the world’s population and accounting for 40% of the global GDP. This includes both advanced and rapidly growing economies, such as the EU, EFTA, and Hong Kong, as well as major regional players like Türkiye and China. Additionally, Georgia has a free trade agreement (FTA) with all CIS countries. As demonstrated below, Georgia’s network of FTAs is both extensive and distinctive.

In the decade leading up to the implementation of the DCFTA, Georgia’s trade with the EU grew at an average annual rate of 16%, while exports from Georgia to the EU increased by 18% annually. Notably, this growth occurred without any bilateral free trade agreement in place. Therefore, it was anticipated that the DCFTA could drive significant trade expansion with the EU, albeit more likely in the long rather than the short term.

Deterioration of Trade

The entry into force of the DCFTA coincided with Russia’s gradual lifting of its trade embargo, which started in 2013 and led to a steady increase in Georgian exports to Russia. This shift was a direct outcome of the Georgian Dream’s policy of resetting relations with Russia. While exports to Russia accounted for only 2% of Georgia’s total exports in 2012, this figure rose to nearly 11% by 2023. Over time, Georgia’s economy has grown increasingly dependent on Russia—a country that occupies one-fifth of its territory and actively opposes Western influence in the region.

A key factor influencing Georgia-EU trade dynamics has been the change in government just two years before the DCFTA took effect. In 2012, the change in power brought an economic policy shift under the new leadership, which was significantly less focused on pro-growth and pro-business reforms aimed at attracting foreign investment, fostering diversification, and driving growth. This policy shift resulted in a slowdown in economic growth.

For instance, between 2004 and 2012, Georgia’s GDP per capita in nominal terms increased fourfold, rising from USD 1,035 in 2003 to USD 4,518. During this period, the average annual GDP growth in nominal USD terms reached 18.7% despite the dual shocks of the 2008 Russian invasion and the 2009 global financial crisis. In contrast, the average annual GDP growth in nominal USD terms slowed to just 6.3% between 2013 and 2023. This level of growth is insufficient for a developing economy like Georgia to achieve substantial progress in economic development and prosperity. Furthermore, much of the recent growth over the past two to three years has been driven by the inflow of Russian capital and immigration in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A retrospective analysis of political and economic dynamics, coupled with the Georgian Dream government’s recent decision to effectively freeze the EU accession process for the entire four-year legislative period, highlights the decline in trade flows between the EU and Georgia.

A retrospective analysis of political and economic dynamics, coupled with the Georgian Dream government’s recent decision to effectively freeze the EU accession process for the entire four-year legislative period, highlights the decline in trade flows between the EU and Georgia. The causes of this deterioration are primarily political rather than economic.

For years, the GD government touted the conclusion of the DCFTA with the EU as evidence of its pro-European foreign policy, positioning itself as the force steering Georgia toward EU integration. However, it failed to implement critical policies and reforms necessary to stimulate economic growth, promote private sector development, and attract foreign direct investment —all of which are essential for expanding trade.

Attracting investment is vital for creating jobs, driving growth, and fostering prosperity in a small, FDI-dependent economy like Georgia, where domestic capital is limited. The DCFTA had the potential to deliver long-term benefits, but only if it had been integrated into a broader economic and trade policy framework aimed at deepening trade and economic ties with the West.

Instead, the GD government’s lack of reforms gradually weakened trade interdependence between Georgia and the EU. This erosion laid the groundwork for the recent decision to suspend Georgia’s EU membership efforts as declining economic ties mirrored the government’s growing anti-EU orientation. With the GD leadership now openly distancing itself from the EU, Georgia’s limited economic interdependence with the EU has left little to constrain or influence this shift.

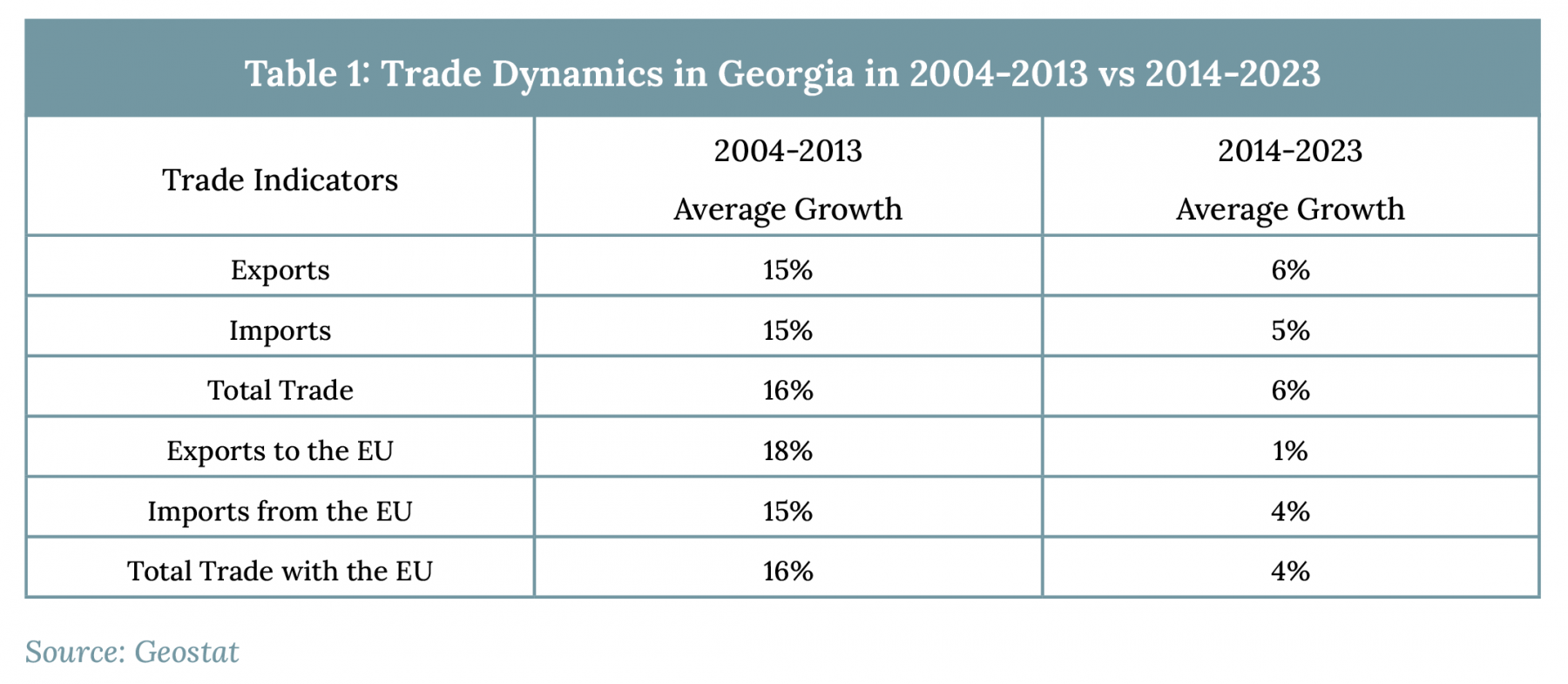

Table 1 below summarizes Georgia’s key trade indicators and compares overall trade dynamics and trade with the EU ten years before and after the entry into force of the DCFTA in 2014. It is clear that just before the entry into force of the DCFTA, Georgia’s overall trade performance was much stronger and grew quickly, even without having a free trade agreement in place. Overall trade in 2004-2013 grew by 16%, whereas the same figure was just 6% in 2014-2024. The exports to the EU also grew by 15% in contrast to just 6% in 2014-2024.

Moreover, since the DCFTA entered into force, Georgia’s export structure by commodity has not changed significantly. However, several new products (e.g., kiwi, dried lemon, persimmon, blueberry, quince, fruit jams, honey, pet furniture, and glass bottles) have been exported to the EU market in minimal quantities since 2014.

The initial phase of DCFTA implementation went in parallel with the intensification of Georgia’s trade relations with Russia and the fortification of Russian political and economic influence in Georgia – first disguised under the EU integration objective and now openly visible, manifested among others in the stance of Georgia’s government concerning the Russian invasion in Ukraine, the adoption of Russian type laws, and engaging in open confrontation with Western partners. The rigged elections of 2024 were just a culmination of this trend.

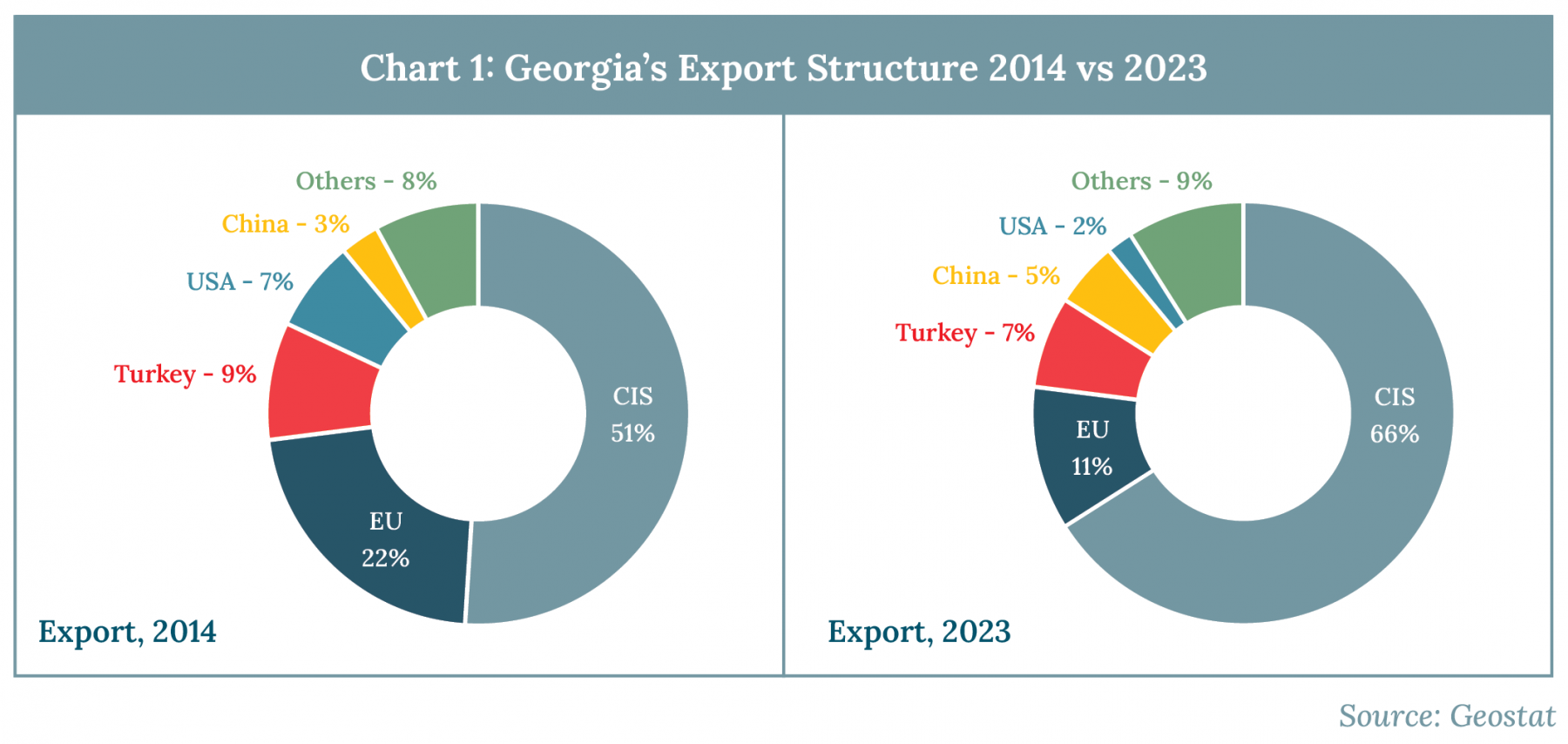

As the chart below demonstrates, Georgia’s share of total exports to the EU was reduced substantially between 2014 and 2023—from 22% to 12%. In the same ten years, the share of the EU and US diminished whereas the share of the CIS increased as did the share of exports to China.

DCFTA’s Positive Impact

Despite the slowdown in EU-Georgia trade relations, the DCFTA has still had a twofold positive impact on Georgia.

First, while the trade-related effects of the DCFTA have been modest, its broader impact on trade liberalization has been substantial. Specifically, the conclusion of the DCFTA catalyzed the initiation and finalization of several other free trade agreements. Agreements were reached with EFTA in 2016 (effective 2017), China in 2017 (effective 2018), and Hong Kong in 2018 (effective 2019). The increased interest in the Georgian market from partner countries was directly linked to the EU free trade deal. Theoretically, Georgia offers expanded opportunities for production within its market, leveraging a relatively favorable business environment to export goods to the EU duty-free. This aspect represents a highly valuable and beneficial by-product of the DCFTA. However, the potential benefits remain underutilized due to the lack of a consolidated government strategy to position Georgia as a trade hub with unique trade opportunities.

Second, the DCFTA has driven significant legal and institutional reforms to meet its approximation requirements. Its implementation has necessitated policy changes, including establishing new state institutions or enhancing existing ones with expanded functions and introducing state control and oversight across almost all areas covered by the agreement. These reforms have increased costs for both private businesses and the state. Ideally, these costs should be offset by deeper economic integration with the EU, leading to more significant trade and investment volumes and, ultimately, higher economic growth.

Overall, Georgia fulfilled DCFTA-related obligations without significant setbacks, at least until the recent suspension of the EU integration efforts by the GD. While trade and economic alignment with the EU have largely remained on track, a thorough assessment is needed to determine whether the implemented changes adequately align with the DCFTA’s objectives and whether the related institutions uphold integrity, transparency, and anti-corruption principles. If Georgia resumes its EU accession efforts, these reforms could establish a strong foundation for eventual EU membership.

In summary, the trade-related benefits of the DCFTA for Georgia have been modest or virtually non-existent so far. There has been no significant growth in trade volumes, and the structure of exports has not undergone substantial change. While the free trade agreement offers opportunities akin to a champagne pyramid, political and democracy-related problems act as an impenetrable layer, preventing the benefits from trickling down to the broader economy. This limited impact must be viewed in the context of deteriorating relations between Georgia and the EU and Georgia’s increasing political and economic alignment with Russia. Without a dramatic shift in Georgia’s foreign policy approach, trade and economic relations with the EU will unlikely improve. Western investors and traders will be hesitant to restore trust without clear evidence that Georgia is committed to its European future and is willing to capitalize on existing economic frameworks. Unfortunately, this seems improbable under the current leadership.